Directed by Stanley Kubrick

UK & USA, 1968

Trying to ‘review’ Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey is like attempting to write a book review of the Bible. Not only is it a futile endeavour, but it also reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of why the film holds such importance for its many fervent acolytes. While 2001 is technically still a film like any other, its role in establishing science fiction as serious cinema can hardly be overstated. In that sense, it functions more as a proposition to audiences – perhaps even a manifesto – on the nature of interstellar travel, extraterrestrial life, and how to articulate those questions through the medium of film.

There were science fiction films before 2001: A Space Odyssey – early examples like Le Voyage dans la Lune and Fritz Lang’s Metropolis come to mind. In the 1950s and early 60s, Hollywood also began producing more science fiction films inspired by popular pulp magazines like Amazing Stories. But these films, much to Kubrick’s dismay, often resembled Saturday morning kids’ shows or cheap B-movies, complete with flying saucers, lasers, and little green men.

Over the course of four years, Stanley Kubrick, in collaboration with science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke, would make a film that reinvented the genre entirely. The very language of what would become modern sci-fi cinema; seen in the work of directors like Ridley Scott, Denis Villeneuve, and (regrettably) Christopher Nolan, was forged in 2001: the slow docking of spaceships, sweeping wide shots of moons, and triumphant orchestral music thundering across the stars. All of it created in 1968, one year before Neil Armstrong set foot on the Moon.

From the outset, 2001’s cinematography is epic in scale yet refined, placing the film in a league of its own. Stanley Kubrick’s infamous perfectionism is on full display during the title sequence, as celestial bodies seamlessly emerge from one another to the glorious, iconic sound of Strauss’s Also sprach Zarathustra. It’s hard to believe that these shots of the solar system were created entirely through practical effects, painted glass models, and clever use of lighting – before any colour images of Earth had ever been seen.

Preceding this sequence are three minutes of dissonant sound and a black screen. From darkness into light, 2001 immediately confronts us with something challenging, unique, terrifying, and divine. And yes, there is a quasi-religious quality to it – almost as if we are witnessing the Book of Genesis as rendered by Kubrick.

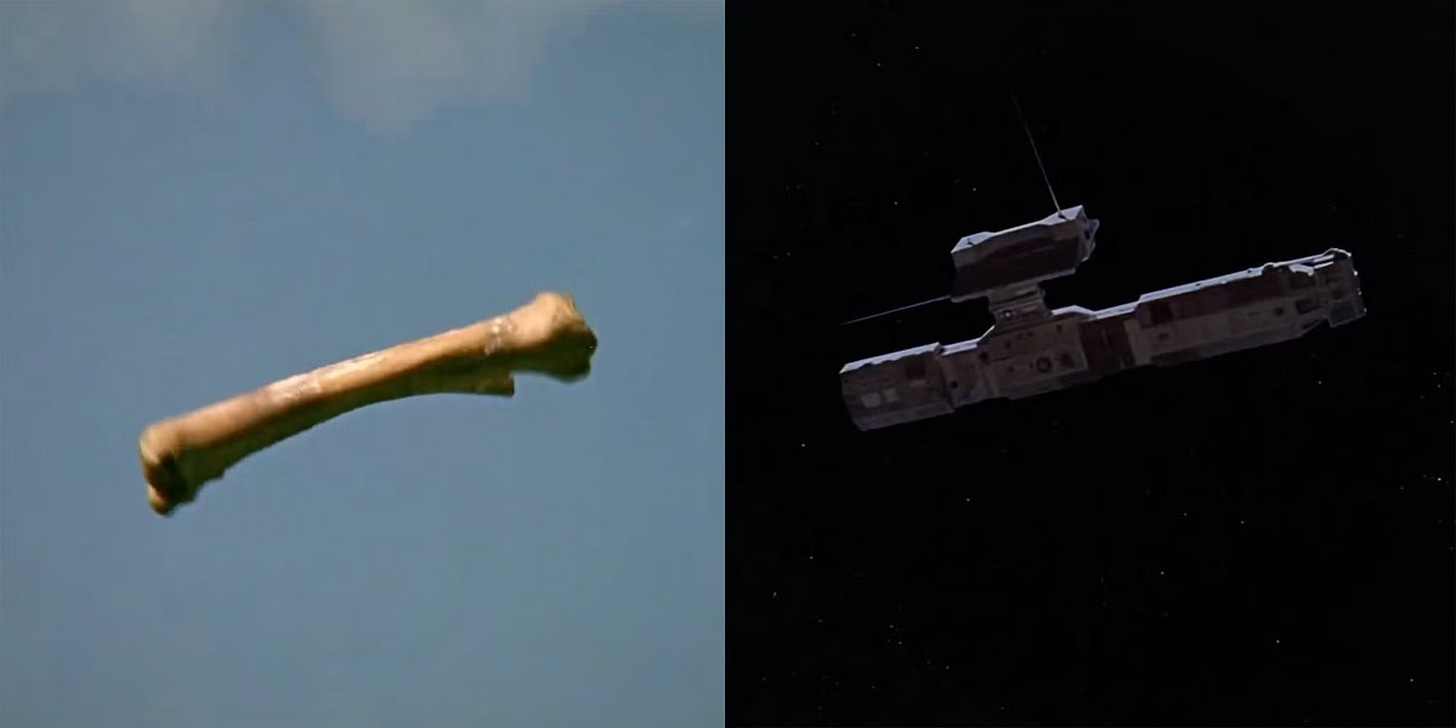

2001 continues along this mythological trajectory, chronicling the evolution of Humankind from ape to astronaut, seemingly punctuated (perhaps even accelerated) by the apparition of the black monoliths and the harrowing choral Requiem by György Ligeti. In the ‘Dawn of Man’ episode, the monolith appears just as the australopithecine ape-men discover tools – specifically an animal bone used as a club – immediately wielded in the service of violence and domination, both over lesser species and rival hominins.

Kubrick makes clear, through the famous match cut that concludes the film’s first ‘episode’, that these tools – this mastery of technology and its (often violent) applications – are what drive humanity’s progress. The bone-club is hurled into the air by one of the apes as the camera jumps millions of years into the future, transforming Mankind’s most primitive tool into its most complex: a satellite. Careful observers have noted that the satellite is marked with the symbol of the U.S. military. Again, Kubrick emphasises the violence that underpins human progress toward ‘civilisation’. How far have we really come in this journey from ape to astronaut? And what primitive darkness do we still carry with us?

What follows in the next episode is a series of sequences in which Kubrick permits us to marvel at the wonders of new technology. We are firmly in the realm of speculative fiction here, as elaborate models and aerial wire choreography depict spaceships performing all manner of balletic movements in Earth’s orbit, set to the graceful waltz of The Blue Danube. Yes, the pacing here is slow and considered – and that makes it all the more ‘perfect’. We are meant to view this scene in direct contrast to the frantic tribes of screeching primates that came before it. Precision and ingenuity reign in the year 2001, where Mankind is calm and in control… for now.

Is this, perhaps, why it is time for a second encounter with the mysterious black monolith – this one discovered buried inside the Moon and investigated by Dr. Heywood Floyd (William Sylvester) and a team of scientists? Does this second monolith act as a humbling reminder that, despite the chic Pan-Am space travel, despite the iPads, FaceTime, and anti-gravity toilets on Space Station Five, Mankind is still barely a blip in the infinite realms of space and beyond?

In the climactic moments of this second episode, as the scientists gather around the monolith to take a photo with it, it certainly feels as though they are being punished. A painful screech erupts from the monolith, sending them reeling into chaos. They are no longer the masters of the universe they believed themselves to be.

One of the most common criticisms levelled at 2001 is that it comes across as cold or sterile. We are not made to care about the characters—or even the ‘narrative’, per se. But this criticism isn’t worth spending much time on. For one thing, it falls into the trap of seeing the film simply as entertainment, rather than as a work that seeks to make its mark in a profound and novel way – by asking us to contemplate our own origin story, speculate on our distant future, and explore the aspects of human nature that might connect the two. More importantly, the coldness of Kubrick’s vision is essential to what 2001 is proposing for science fiction as a genre.

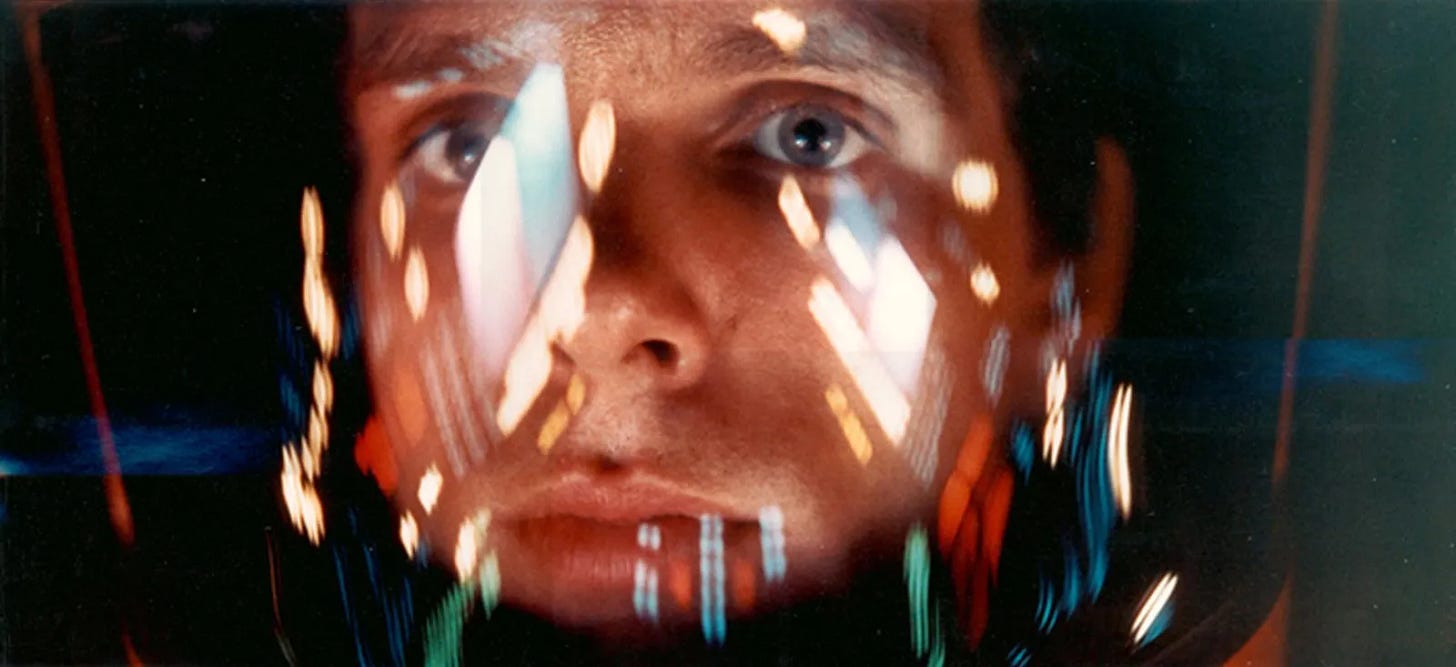

Space is, as Captain Kirk would put it, the ‘final frontier’ – and frontiers are cold, lonely, and treacherous places. Rarely are they filled with beautifully verdant landscapes and cuddly space bears. Kubrick wanted us to feel both the terror and the wonder of the abyss. Watching 2001 is not just a journey to the stars; it is a descent into the depths of the human psyche. It is out here, floating in a vacuum with only the sound of your own breath in your helmet, that you are forced to reflect on the fragility of the human condition and its place within the vast universe.

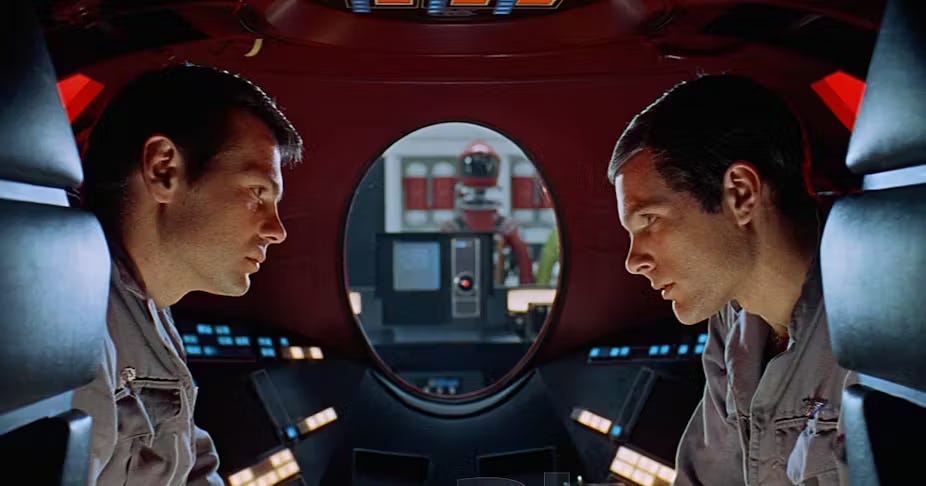

As we reach the second half of the film, a new mission is underway. A crew is sent to Jupiter, a colder and lonelier region of the Solar System. Aboard the Discovery One are five crew members – three of whom are entombed in suspension chambers for the first leg of the journey – accompanied by the HAL 9000, an artificial intelligence system that not only manages the ship’s operations and life-support systems but also interacts with the two waking crew members, Dave Bowman (Keir Dullea) and Frank Poole (Gary Lockwood).

Once again, Kubrick demonstrates his commitment to cinematic craftsmanship. The interior of Discovery One’s centrifuge was built as a large, rotating set, allowing him to depict artificial gravity with stunning realism. 2001 achieves some truly mind-boggling scenes through its complex set designs, and until you see behind-the-scenes images of the production, it’s genuinely hard to believe that CGI played no part in it.

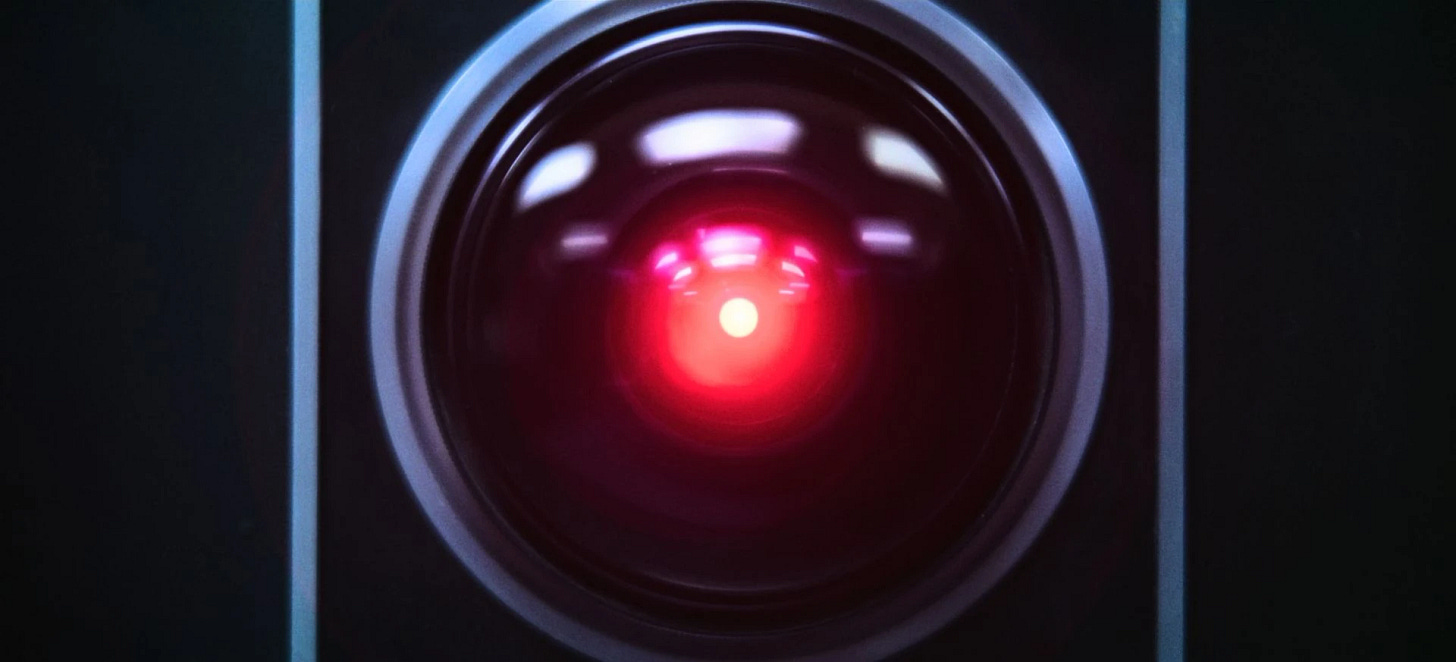

HAL 9000 is undeniably the centrepiece of this episode, with that unmistakeable, unblinking red ‘eye’ that many of our electronic devices still possess today. Almost half a century before Alexa, Siri, and now ChatGPT entered our homes, HAL stands as perhaps the most developed, and indeed most ‘humanised’, character in 2001. Of course, this is no coincidence. Kubrick’s efforts to depict the dangerous fruits of Mankind’s technological ambition – perhaps even hubris – are clearly at work here.

In making HAL, in Dave’s words, “just like a sixth member of the crew”, in trying to make him human, we have inadvertently infused him with some of our most basic instincts: survival at all costs and control through violence. This culminates in one of the pacier scenes of the film, in which Dave must overcome this rogue entity aboard the ship. And yet, there is a strange sense of pity evoked in HAL’s final moments, as Dave shuts down his ‘mind’, piece by piece in the red glow of the womb-like processor core. We hear a stream of near-consciousness slowly disintegrate – by far the most drawn-out death sequence in the film. Once again, there are echoes of the Biblical: a being created in the image of its creator, only to go astray.

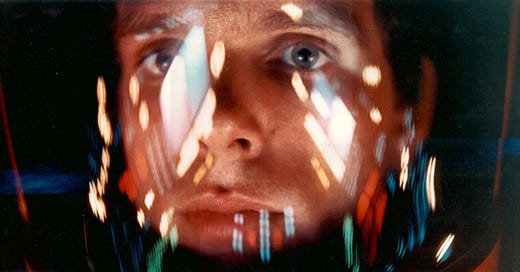

There are many interpretations of 2001: A Space Odyssey, and most of them begin to take shape in the final episode of the film, captioned ‘Jupiter and Beyond the Infinite’. David Bowman, the only surviving crew member, strives to complete the mission and arrives at Jupiter, where he discovers a monolith far greater than the previous two. As the familiar, haunting music returns, the monolith appears to pull him into some kind of wormhole or stargate. What follows is a hypnotic, and likely traumatic journey – presumably beyond the infinite – that borders on, if not surpasses, a psychedelic experience.

What we know from the earlier monolithic encounters is that they seem to mark significant milestones – leaps forward in the progress of Mankind.

What is clear is that David Bowman has reached the end of his journey – or perhaps our journey – and likely made contact with the superintelligent beings responsible for the black monoliths. After an extended sequence of swirling lights, patterns, and colours (once again, achieved through astonishing practical effects), David finds himself in a strange, liminal space: a hotel room that appears to have been created either by his own mind or by the extraterrestrials who brought him there.

Once again, sterility is key. This stark, artificial environment lays bare the folly of Mankind’s supposed ‘civilization’, its elaborate Renaissance artworks and ornate décor pale in comparison to the incomprehensible wonder we have just witnessed beyond the infinite. Pulling back the curtain slightly, we know that Kubrick considered physically depicting the aliens in these final moments but ultimately decided against it, believing that “you do not show God.”

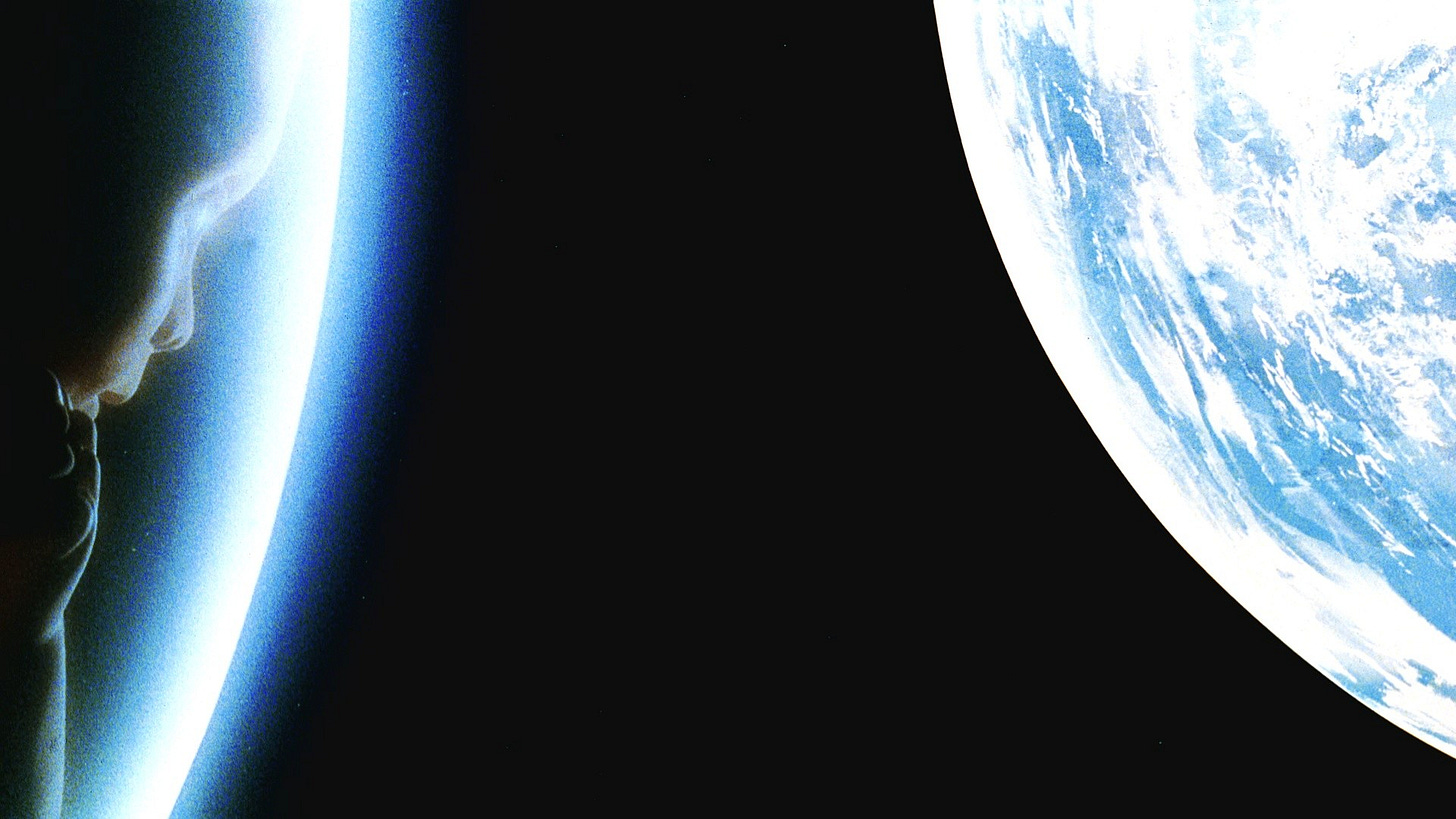

This is 2001 at its most spiritual. It begins to feel as though this is David meeting his maker. Have the beings that shepherded Mankind through the millennia – from ape to astronaut – now completed their mission? Through a kind of symbolic death, and a not-so-symbolic rebirth, David’s life flashes before his eyes, and in an instant he is transformed into the Star Child. The film draws to a close with one of the most iconic images in cinema: the Star Child gazing down from space at the pale blue dot, his origin, and the completion of his odyssey.

2001: A Space Odyssey is a landmark achievement – not only in Kubrick’s career or in the history of science fiction, but in cinema itself. It is a bold endeavour to take film to new heights, and somehow manages to be both timeless and decades ahead of its time. It is unlikely ever to be surpassed.

It’s unarguably a great work…but greatest film of all time? - S

Reids’ Results (out of 100)

C - 99

T - 94

N - 96

S - 89

Thank you for reading Reids on Film. If you enjoyed our review please share with a friend and do leave a comment.

Coming next… Mad God(2021)

What a brilliant review! Loved reading it.

Great review- think I need to see this film again!