Directed by Mahamat-Saleh Haroun

Chad, 2002

A cold open: a man with a suitcase strides across the desert dunes in silence. He turns 180 degrees to face the camera and looks directly at us, the audience. He turns again and walks purposefully away. Once out of shot the credits and the music play … yes, this is cinema.

Abouna was the director Mahamat-Saleh Haroun’s second feature film. Living in France since the early 1980s, having fled the civil war, he is Chad’s only filmmaker of significance. He returned to make this fable about two boys searching for their father with a limited budget, having to send the dailies to Paris for processing. A simple tale perhaps, but spellbinding in the way it unfolds on the screen.

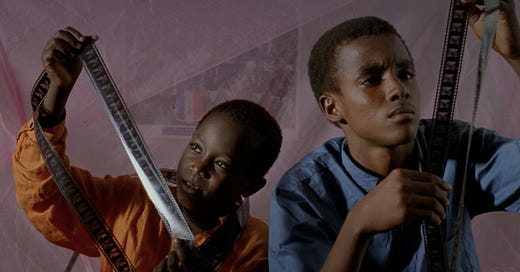

Tahir and Amine wake one morning to find their father gone. His absence is never explained and they later spot him playing the lead in a film they watch in Chad’s only cinema. But is it really him? The boys steal a reel of the film to help them track him down. When they inevitably get caught their mother sends them both to a Koranic school to learn some discipline. Needless to say, that is just the beginning of a new adventure.

Abouna is deliberate in its pacing and naturalistic in style. Haroun, despite or perhaps because of the challenges of shooting in this setting takes his time in allowing the narrative to develop. The cinematography is striking with the use of vivid colours, particularly in the lead characters’ dress, to guide your eye around the frame. The long takes bring to mind the films of Studio Ghibli. The small details in the performances such as the boys playing keepie-uppie in the alleyway and their mother sitting at her sewing machine, as well as the mise-en-scene are the elements that give life to the film. This considered observational perspective conveys an experience of childhood, a world removed from that of adults, that is all too rarely seen on screen. The most dramatic moments, and one in particular, happen out of shot and then the story moves on. No pondering, no reflection.

The acting from a cast of largely non-professionals is in some cases admittedly limited but that doesn’t detract and we have fine performances from the two boys. Their dynamic is compelling whether they are larking about, walking on hands across a rubbish dump, or simply sitting in the street and watching life pass by. Another highlight is Mounira Khalil, the Chadian singer and actress, playing a deaf girl in a gold dress who acts as a spiritual guide leading Tahir, the older of the brothers, to freedom. That spiritual element is manifest elsewhere. Framing characters in a doorway has a distinguished history in film: think of John Wayne in The Searchers and Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz. Often the door symbolizes a physical representation of a psychological threshold or barrier and in Abouna Haroun seems to be using it to foreshadow the passage of a character from one world to another.

Escaping to freedom is a central theme here and in that Abouna has a lot in common with the great Senegalese film Touki Bouki. Both films show adolescents breaking away on motorbikes and they also share a strong French New Wave influence. Fragmented and discontinuous editing, jump cuts, long takes, and breaking the fourth wall are all on display. There are also frequent references to cinema itself, notably the two boys rolling a canister of film along the street and then the posters outside the movie theatre: The Kid and Salaam Bombay, both films about homeless kids. That influence may be unsurprising given that Chad and Senegal are Francophone countries but both films use it to develop their own highly distinctive sensibility.

Abouna translates as ‘Our Father’ in English and the film does speak to the responsibility of fathers and mothers from a child’s perspective. Amine overhears their mother complaining about their irresponsible absent father. We have no idea why he leaves. The boys find out that he hasn’t been going to work for two years despite leaving the house every morning, so is he looking for work or is he looking for escape? They look up the definition of irresponsible in a dictionary and find ‘Someone who’s not responsible’. So Amine infers, “our father was not responsible for leaving”. After all when he was at home he would play football and read them stories whereas their mother is largely a stolid, background presence. But it is their mother that bears the burden of their welfare and that burden eventually becomes overwhelming, until she too is liberated by Tahir in the all too-brisk closing scenes that by intention or not, have an impression of wish-fulfillment about them. However, this is a minor flaw in such a rich and luminous film. A film well served by an excellent soundtrack featuring the Malian guitarist, Ali Farka Toure, and the composer Diego Mustapha N'Garade who has a cameo role as the boys’ affable Uncle Adoum. After Adoum’s guitar playing is coldly received with a bucket of water he complains, “We don’t like artists here.” We can only hope this is an ironic remark, given the insights that Haroun’s Chadian cinema delivers.

Reids’ Results (out of 100)

C - 79

T - 76

N - 69

S - 78

Thanks for reading Reids on Film. If you enjoyed it please share with a friend and do leave a comment.