Directed by Akira Kurosawa

Soviet Union & Japan, 1975

It is hard to imagine that one of cinema’s most celebrated film directors, Akira Kurosawa – he of Rashomon, Ikuru, Seven Samurai, and Ran – could have ever had a barren spell. In the early 1970s however, he really was struggling. Kurosawa’s first colour film, Dodes’ka-den (1970), was a critical and commercial failure and led to the director becoming severely depressed. He attempted to end his life in the following year.

In Japan attitudes towards his work had changed. Kurosawa was considered ‘too Western’ in his approach to film and couldn’t get any finance from a Japanese studio. So who came to the rescue? Not the Americans – Lucas, Coppola and Scorsese who had all become devotees – but the USSR. The Soviet studio Mosfilm, producers for Andrei Tarkovsky and Sergei Eisenstein, offered him a chance to shoot a film in Siberia with complete creative control. Out of that opportunity Kurosawa produced yet another masterpiece.

Surprisingly he chose to adapt a 1923 memoir by a Russian army captain and explorer, Vladimir Arsenev. Dersu Uzala was a book about his exploration of the Russian Far East in the early 20th century and his developing friendship with a Nanai hunter, the eponymous Dersu. The film begins in 1910 with Arsenev looking for the grave of the friend he has buried three years earlier, in a forest that is now being felled for redevelopment. He reflects back to their first meeting in 1902, when Arsenev and his platoon working as surveyors encounter Dersu in the wilderness. An experienced hunter and guide, with an extensive knowledge of the land, they invite him to join their expedition.

He soon demonstrates his worth by saving Arsenev’s life once, then again following a second expedition in 1907.

But over time Dersu’s eyes begin to falter. He misses a shot at an attacking tiger and a hunter is no good without his eyesight. Dersu joins Arsenev at his family home in the city of Khabarovsk but he soon realises that he is now a man out of time and returns to the wilderness.

Kurosawa has a way of composing a shot that no one else can match. He really is the master of movement: finding drama in the flowing water, falling rain, a raging fire, and even in a curling wisp of smoke. He also insisted on shooting on location, amidst mud, fog, and rain. This film required two years on location … two years! And they had to shoot (metaphorically) a Siberian tiger. Who would do that these days in our CGI world?

One of Kurosawa’s assistants, Teruyo Nogami, wrote a book about her years working with the director. She gave it the title: Waiting on the Weather.

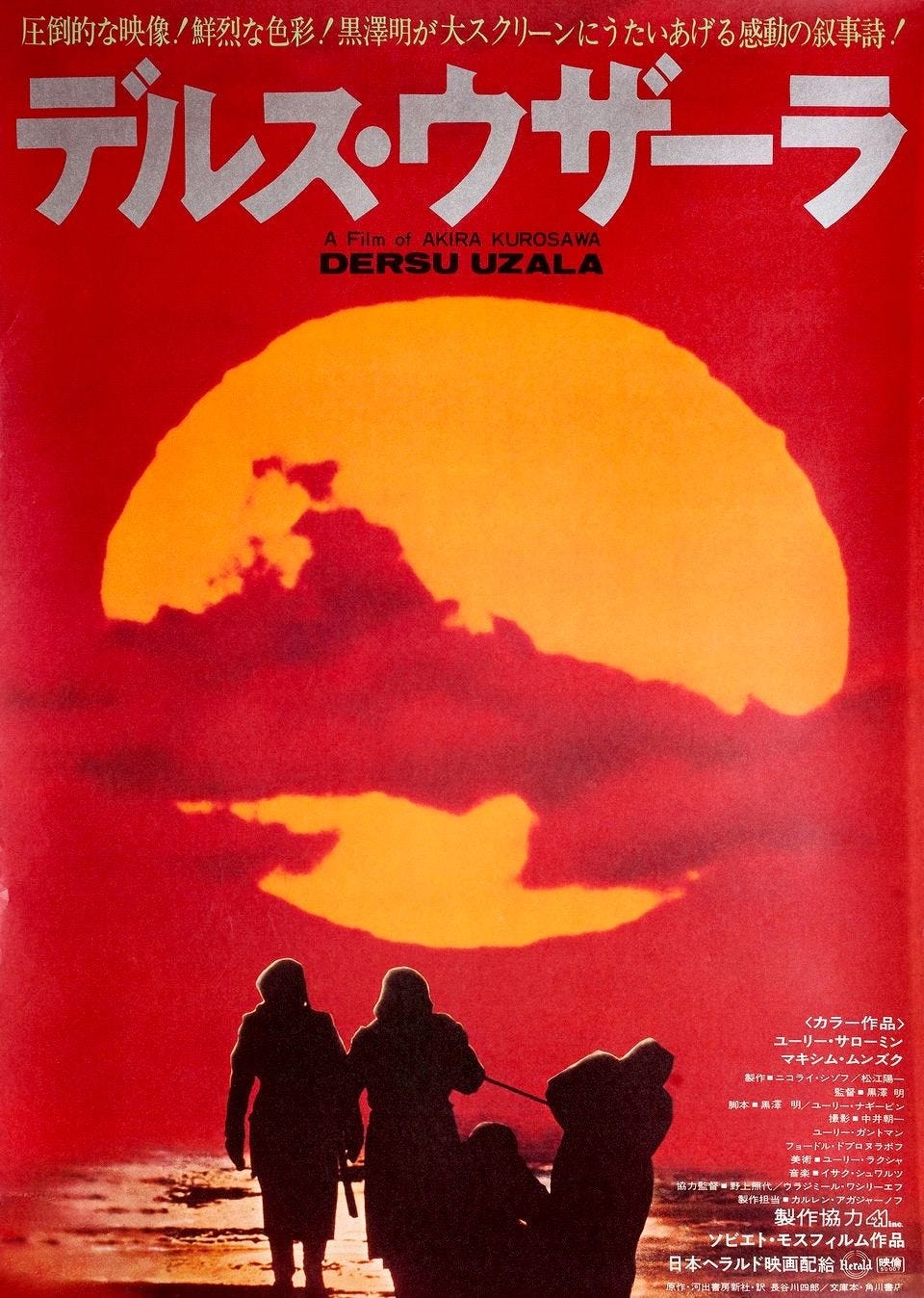

Through his stunning use of photography Kurosawa transforms what is a fairly simple story into something enchanting on a bold and sumptuous 70-millimetre canvas. The forest is a palette of reds, greens and browns and he masterfully uses light and shadow to give the scenes weight. From the golden light of sunrise to the deep reds of the sunset every shot is a painting.

Central to the story of course is the relationship between Arsenev and Dersu, beautifully acted by Yuriy Solomin and Maksim Munzuk. A pair of characters from completely different worlds, Dersu the wizened old man seems to be too good to be true in the first half where he shows near-superhuman wilderness skills and demonstrates such generosity of spirit.

Dersu Uzala: Fire is people. When fire angry, taiga burn for many days. Fire get angry, it frightening. Water get angry, it frightening. Wind get angry, it frightening. Fire, water, wind - three mighty people.

We learn that Dersu lost his family to smallpox but otherwise know little of their lives off the trail. The first half climaxes with the two of them caught in a snowstorm that has to have been genuine. Racing against time, they are fighting for survival as Dersu skilfully builds a sea grass shelter that will save the life of both of them. A scene that would have been worthy of the price of admission on its own.

The director George Lucas acknowledged Dersu as the inspiration for his character Yoda, and anyone who has seen the best of the Star Wars films, The Empire Strikes Back, will recognise the source for Han Solo and Luke Skywalker surviving a night in the snowscape.

At the start of the second part of the film Dersu inexplicably loses his pipe - a foreshadowing. Progressively robbed of his abilities by the unforgiving process of aging, as the second half leads us to the inevitably tragic ending their bonding through experience feels genuinely authentic. Paradoxically, the civilisation that Arsenev brings to Siberia through his surveys spells the end for Dersu.

Arsenev: Man's measure is dwarfed by the vastness of nature.

Perhaps Kurosawa felt that he too was a character of the past. His later films, in particular Kagemusha (1980) and Ran (1984), were existential meditations on death. There is also something of the elegiac tone of those old Westerns of the great Hollywood director John Ford. The opening shots of the frontier towns, the old friends sitting by the campfire – Kurosawa owes him a debt. Too Western for a Japanese director? Humanity has no borders.

A slow burn film that is definitely worthy of its length - T

Reids’ Results (out of 100)

C - 80

T - 79

N - 85

S - 83

Thank you for reading Reids on Film. If you enjoyed our review please share with a friend and do leave a comment. We will back next week…