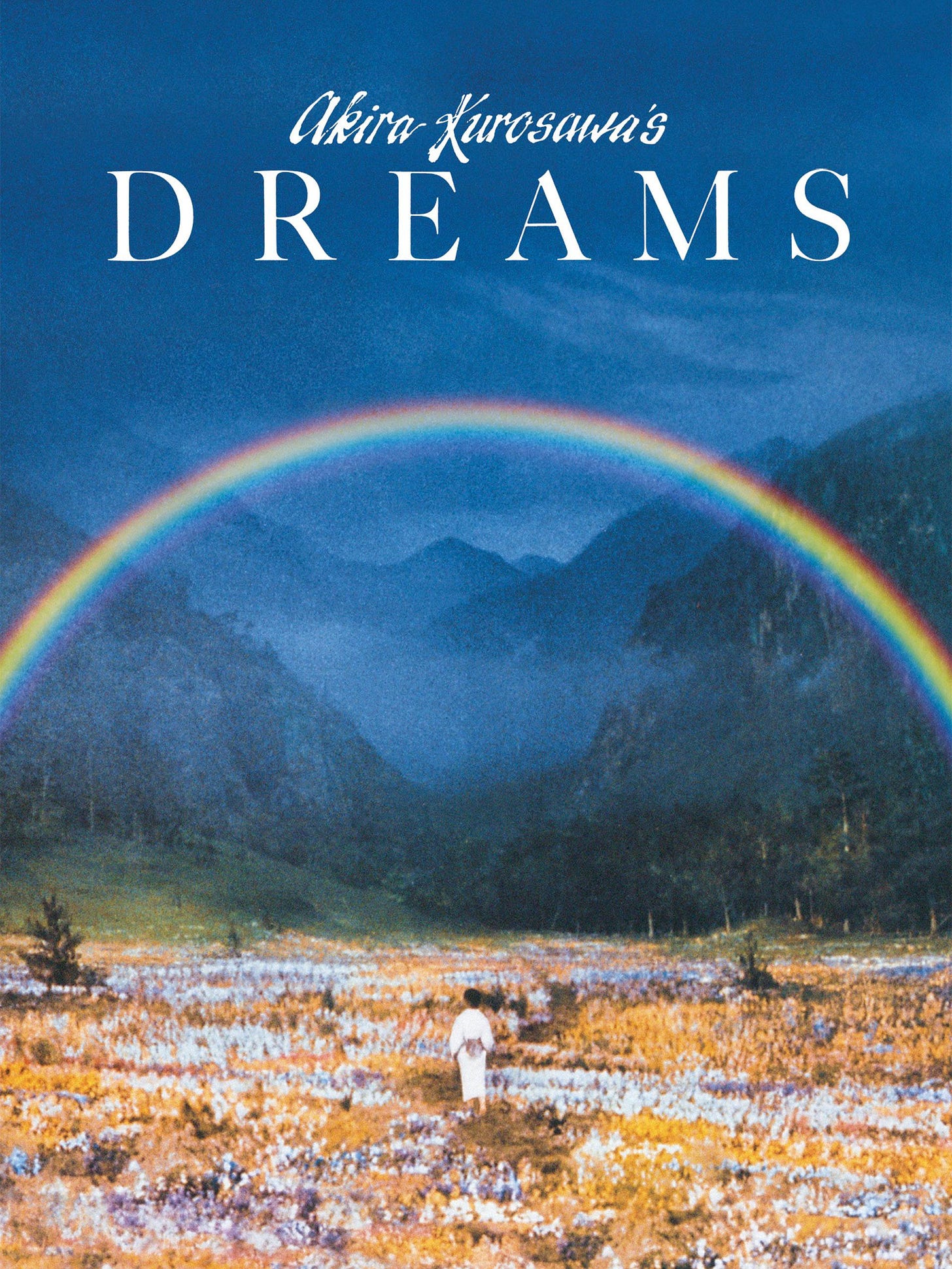

Directed by Akira Kurosawa

Japan, 1990

How often do you remember the detail of your dreams? On occasion I will have a dream so vivid, so rich, that I will spend all morning talking about it – but by the following day it has gone, fragments slipping away, like sand through my fingers. Perhaps I should start keeping a dream journal, writing them down. If I did, what would they look like on the big screen? That’s precisely what Akira Kurosawa has done with his late, penultimate film Dreams.

Kurosawa is rightly celebrated as one of cinema’s greatest directors. Over the course of a 57-year career he made thirty feature films, many of them – Seven Samurai, Ran – epic in scope. Dreams is certainly epic, but a very different film indeed. Composed of eight visually striking vignettes, it is certainly his most personal and introspective work. One of the few films he wrote without a collaborator, its only continuity lies in the presence of a character representing Kurosawa himself. Journeying through the stories, from childhood to an adult, he is recognisable only by his trademark cap.

Dreams opens with a young Kurosawa leaving his home on a sunny morning after a downpour. His mother warns him:

Rain in bright sunshine. It’s when foxes go courting in the forest. But they don’t like to be seen by people.

The forest has an enchanting, fairytale quality, reminiscent of the land of Oz. Of course, the boy finds the foxes: a procession of elegantly dressed creatures walking on two feet. They are heading to a wedding. Such stuff that dreams are made of – but there is a sharp twist. The foxes spot him hiding behind a tree.

The boy flees home only to be met by his dour mother who bars his entry:

You went and saw something you shouldn’t have. I can’t let you in now.

She presents him with a sheathed dagger:

They say you must now kill yourself.

This is a film that catches both the beauty and the terror of dream logic.

A later sequence, The Blizzard, is shot in a starkly modernist style. Four mountaineers roped together, struggle through a relentless snowstorm. Fatigue and despair set in, and one by one they give up and collapse. The screen is awash with the colour blue, the men are sculptural in form, more beast than man. This could be a painting by Paul Cézanne.

A spirit woman appears before the last man standing and urges him to lie down in the snow and sleep:

The snow is warm, the ice is hot.

Tempting though this seems, he rejects her siren-like calls and struggles onward. The sky soon clears, the snow stops falling, and their camp is revealed before them. The men have survived. It’s an optimistic moment but from that point onward Dreams shifts into far bleaker territory.

Kurosawa gives us three films that deal with war, nuclear catastrophe, and a post-apocalyptic world haunted by demons. The director witnessed the Tokyo earthquake of 1923 and in Mount Fuji in Red, he depicts the volcano erupting as nuclear power plants go into meltdown. A reflection on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but also a fear for our future. The imagery is surreal, almost cartoonish in effect – all the more jarring coming from a filmmaker known for his humanism.

What is also striking is Kurosawa’s melding of form, the way Dreams is constructed: Japanese Noh theatre, sci-fi, and animation all make an appearance. Sometimes this works, sometimes it doesn’t. In Crows, the director wends his way through an arresting series of Van Gogh’s landscapes. And then the artist himself, Van Gogh, turns up played by Martin Scorsese. With his New York accent, he explains his bandaged ear thus:

Yesterday I was trying to complete a self-portrait. I just couldn't get the ear right, so I... cut it off and threw it away.

Seemingly, a rare mis-step by Kurosawa, but I guess these are his dreams aren’t they?

The concluding story, The Village of the Watermills, sees Kurosawa return to the beauty of the forest. There he meets an elderly man (played by Kurosawa stalwart, Chishū Ryū), who sitting amid an array of elegantly constructed wooden waterwheels, explains how the villagers have rejected modern technology. They live a life where the days unfold in golden light, traced by the rhythms of nature rather than a ticking clock. Mirroring the beginning of Dreams, a procession passes them by, but this is not a wedding, rather a funeral. It is, however, a celebration of a life lived: bright colours, clashing cymbals and pounding drums.

And yet this joyful endnote cannot erase the harrowing scenes that came before. Kurosawa himself said the role of the artist ‘is not to look away’ and he certainly follows that credo with Dreams. The Village of the Watermills hints at a reverence for a past unencumbered by the burdens and hazards of progress, but what an achievement by a filmmaker, looking back on a career stretching back decades, yet embarking on his first experimental film at the age of 80.

Dreams is kind of wildly un-Kurosawa, and yet maximum Kurosawa - C

ReidsonFilm’s last encounter with Kurosawa:

Reids’ Results (out of 100)

C - 82

T - 80

N - tbc

S - 80

Thank you for reading Reids on Film. If you enjoyed our review please share with a friend and do leave a comment.

Coming next… London(1994)