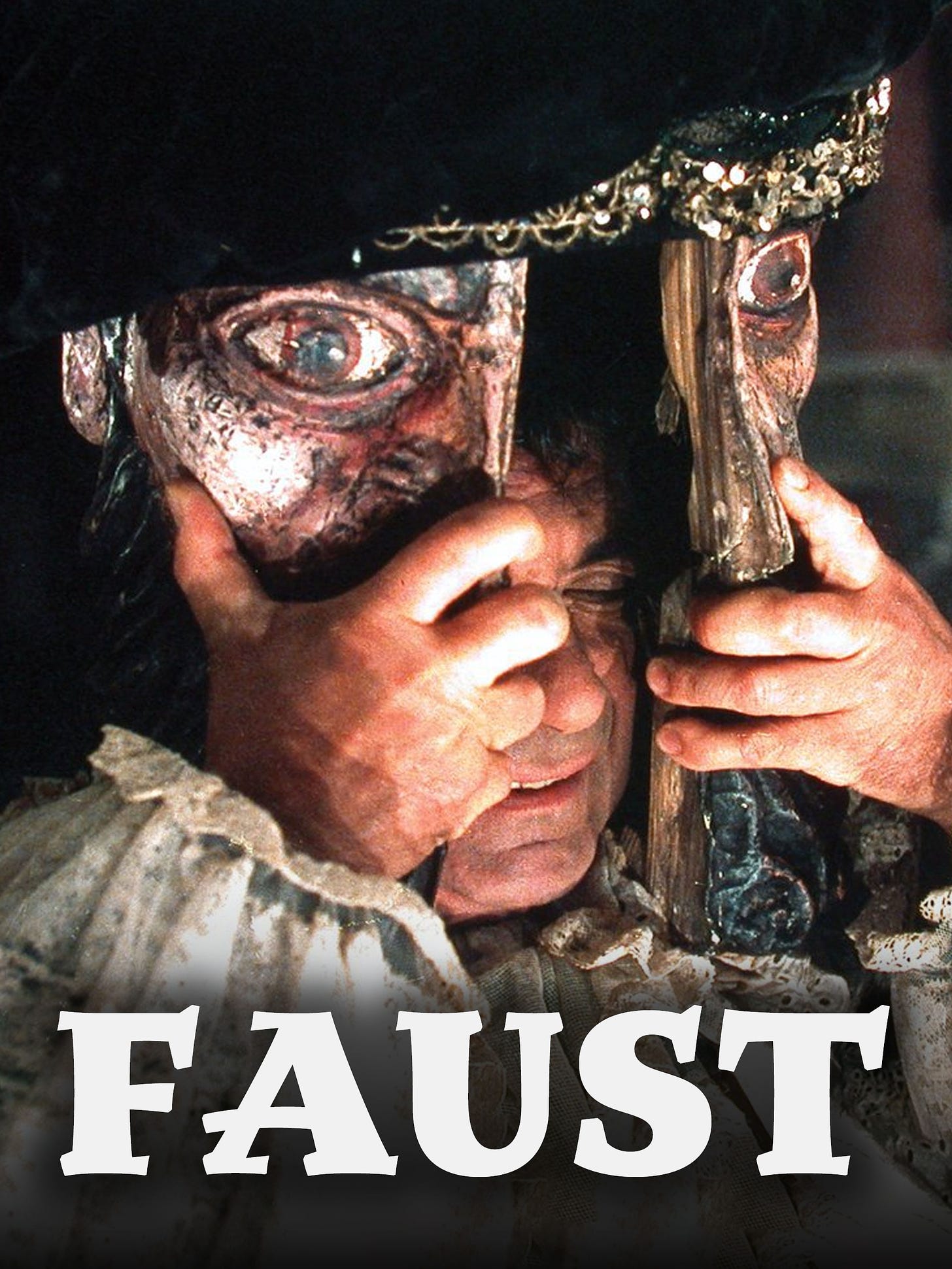

Directed by Jan Švankmajer

Czech Republic, 1994

As ReidsonFilm approaches our 100th publication here on Substack, we thought we would try something a little different. We are planning to record a podcast where our readers have the opportunity to ask a question. Apparently the term is an AUA episode, which means you can ask us pretty much anything - film-related or not. So, if you have a question stick it in the comments box and we’ll see what happens.

A man dressed in a magician’s cloak pursues a woman. Actually, she is not a real woman but a life-size marionette. She falls into a hole. The man shines a torch into the hole and follows her. It is a charnel house packed with bones. He finally catches her, lays her on top of a sarcophagus and seduces her. But something is not right: we can see strings controlling her, pulled by a puppeteer, and her feet are not the feet of a woman, they are claws. The man pulls off her mask and all is revealed. He is having sex with Mephistopheles, the Devil’s agent.

You are now in the world of one of cinema’s few true surrealists: Jan Švankmajer. The film is Faust, Švankmajer’s second feature film following Alice, his retelling of Lewis Carroll’s fantasia, Alice in Wonderland, another story that defies the rational.

Švankmajer was born in Prague in 1934 when the Czech Republic formed half of Czechoslovakia. He grew up in the postwar Communist state, studying puppetry before moving into theatre. A self-described ‘militant surrealist’, when he started in films his work involved a collage of stop-motion animation, puppetry, opera, and live action. And that is what we witness in Švankmajer’s version of Faust – the legend of Dr Faustus who sold his soul to the demon, Mephistopheles, in return for worldly knowledge and pleasure.

The story is well known but also based on a historical figure Johann Faust, a 16th century alchemist and magician. A subject fit for retelling and there have been plenty. Starting with Christopher Marlowe’s The Tragical History of Dr Faustus, there have been operas, a silent film by the great FW Murnau, and perhaps most famously Goethe’s epic poem, Faust.

Švankmajer borrows from, or riffs on, all of these, particularly Marlowe’s play but he bookends the drama with scenes from 1990s Prague. This, however, is not the Prague of chocolate-box castles. Švankmajer’s Prague is seedy, downbeat, and short of cash. Much the same can be said about Faust himself, played by Petr Čepek. No glorious necromancer, but a shabbily dressed civil servant who lives in a dismal apartment where a black rooster defecates all over the floor. He picks up a map being handed out at the Prague Metro that shows a location marked with a red dot. Initially dismissive, he changes his mind and follows the map into a tenement block where he finds a labyrinth of gloomy corridors. On the way Faust passes a speeding red car which narrowly misses him, and as he enters the building, he is almost bowled over by a man running as if to make an escape. Warning signs perhaps, but they go unheeded.

Somehow Faust then ends up backstage in a theatre where an audience awaits upfront; he is surrounded by people, puppets, and props. Here it is that he encounters two marionettes, an angel and a demon, and he seals the deal. Mephistopheles will serve Faust’s bidding for 24 years at the end of which the Devil will take Faust’s soul. What follows is a mélange of farce, horror and agitprop theatre. Faust finds a giant glass flask, inside of which a lump of clay grows into a baby. He places a written incitation into the baby’s mouth, and it springs to life. But within moments it ages, rapidly until we are left with a jaw-clicking skull. Echoes of the Jewish Legend of the Golem – this is certainly not the land of Wallace and Gromit.

Back to those puppets, which come from the Czech marionette tradition, when life-size they really are unnerving, particularly as Švankmajer blurs the line between the puppets and real human bodies. It is a recognised cinematic device to switch medium in film to distinguish between the waking world and that of a dream: think of black-and-white Kansas becoming Technicolor Oz. Švankmajer mixes it all up so you have no idea where that division lies. When a marionette version of Faust agrees to sign his contract with Mephistopheles in blood, a laceration in his arm draws the real thing.

Faust is a film brim-full of ideas and references – to philosophy, history, and of course politics. Metaphor and allegory: a difficult line to tread when you are working under the gaze of the Soviet censor. Splicing scenes from daily life in Czechoslovakia into an animation in Švankmajer’s short film, Leonardo’s Diary, resulted in the film being banned and him being ‘rested’ for about ten years. The first film he made on his return to filmmaking, 1983’s Dimensions of Dialogue was also banned although on this occasion the censor couldn’t say exactly what is was they were objecting to.

His use of logic-defying narrative helped outfox the authorities but did Švankmajer push far enough? This is a question raised by the filmmaker himself when Faust conjures up Mephistopheles, who appears as a grotesque clay head with horns and tusks. Horrified, Faust looks away and when he looks back the head has changed shape, becoming an identical image of Faust, a doppelgänger.

The dream logic of Faust brings to mind the work of that Viennese neurologist… you know, the one that founded psychoanalysis. But Švankmajer’s singular vision comes from another European city, Prague; the city of Franz Kafka, where a man can wake up one morning and find that he has been transformed into a giant insect.

At the midnight hour your body and soul are mine…

Faust will of course attempt to renege on his bargain with the Devil, but can a man ever elude his fate? As he makes his escape from that tenement block, he passes a man who is just coming in, looking quizzically at a map with a red dot on it. Faust runs across the road just as that red car appears again but this time it doesn’t miss him. From underneath the car, a pool of blood spreads. A policeman arrives and opens the door to the car. There is nobody inside.

A curious footnote: Petr Čepek, the actor playing Faust, died in the week of the film’s release in Prague. He had named the cancer that would kill him Mephisto.

There are two schools of thought about Jan Švankmajer: those who have never heard of him, and those who recognise him as a great filmmaker. If you belong to the former, you could do a lot worse than give this 13 minute short, Jabberwocky, a try:

Reids’ Results (out of 100)

C - 77

T - 75

N - 77

S - 79

Thank you for reading Reids on Film. If you enjoyed our review please share with a friend and do leave a comment.

Coming next… Mephisto(1981)

Kewl.

POI, Freud wasn’t Viennese but born in Příbor, Moravia. And deffo made a deal with Mephistopheles.