Directed by Werner Herzog

West Germany & Peru, 1982

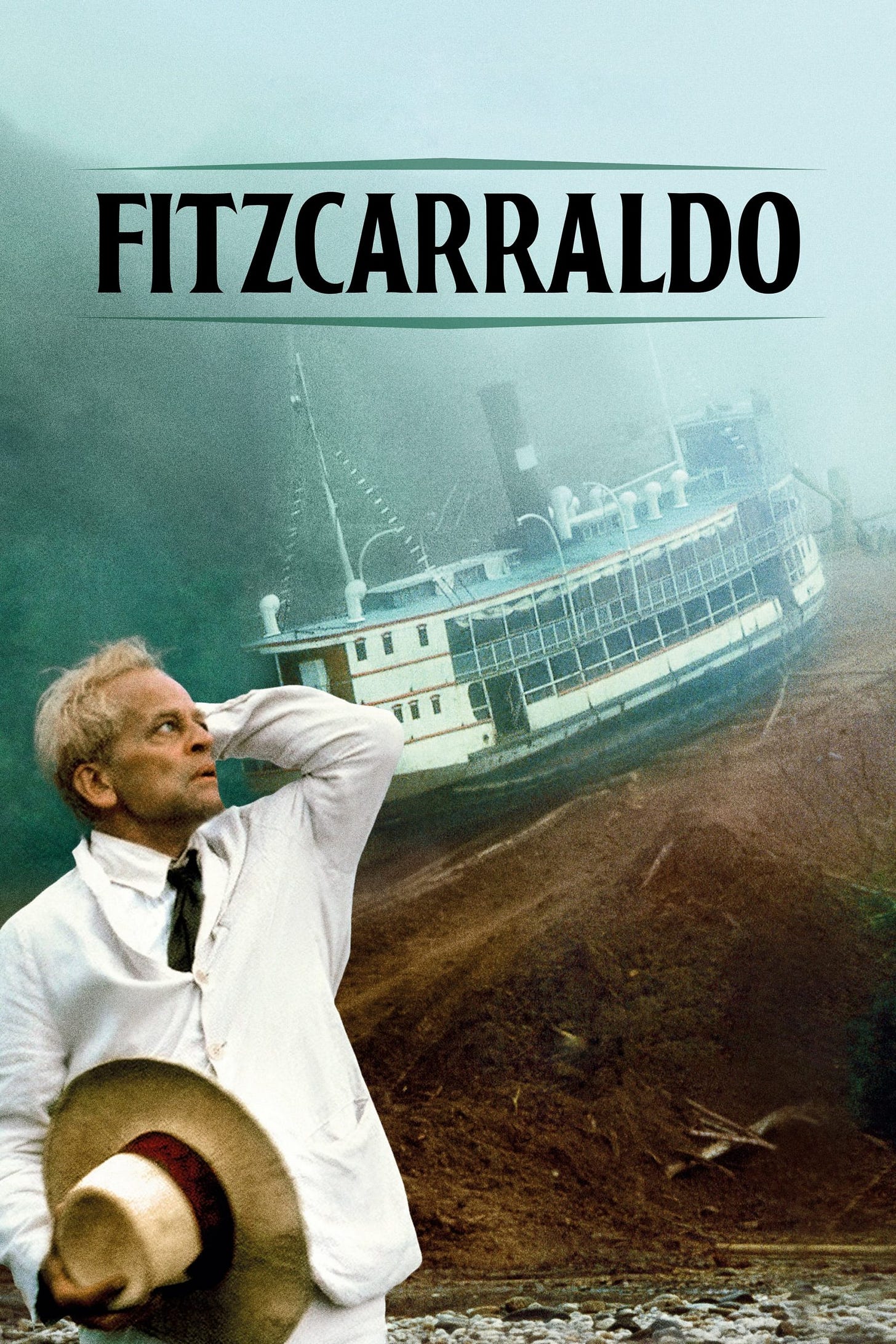

This week’s film opens with a panoramic sweep across the Amazon rainforest, shrouded in fog, and accompanied by the haunting echo of a choir. As the chorus fades, we cut to an ornate opera house, and then to a man rowing frantically toward shore with his mistress (Claudia Cardinale) anxiously seated behind. “Come on, we’re late!” he cries, his distinctive German accent immediately revealing him as the actor Klaus Kinski. Their destination: the opera, and a performance by the great Italian tenor, Enrico Caruso, in Giuseppe Verdi’s Ernani.

Fitzcarraldo marks ReidsonFilm’s fourth encounter with Werner Herzog, three of which feature Klaus Kinski in the lead role, and two in the Amazon rainforest. The opening shot immediately establishes the tone of the film, echoing Herzog’s earlier epic, Aguirre, the Wrath of God, produced a decade earlier. Here, Kinski plays the role of Fitzcarraldo, a less cruel and perhaps more sympathetic lead than Lope de Aguirre. Rather than conquest or greed, Fitzcarraldo is driven by his passion for opera and his desire to bring the voice of Caruso to the indigenous inhabitants of the jungle. And not just on a gramophone record, but in person.

Fitzcarraldo here, is Brian Sweeney Fitzgerald, an Irishman based on erm… a Peruvian rubber baron, Carlos Fitzcarrald. Herzog’s picture unfolds during the rubber boom of the early 20th Century. To fulfil his dream of building an opera house in Iquitos, Peru, and introducing opera to the Amazon, Fitzcarraldo needs a lot of money. His previous exploits, including an attempt to build a Trans-Andean Railway, have ended in failure. Rubber is the source of fortune in this land, as made evident by the local rubber barons’ extravagant displays of wealth: feeding champagne to horses and banknotes to fish, just to experience the thrill of losing money.

Fitzcarraldo manages to secure the only unclaimed parcel of land containing valuable rubber trees, land left untouched as the river access is barred by a series of deadly rapids. However, he identifies that a nearby river offers a solution, with just one obstacle: it would require hauling his steamboat overland, over a steep hillside. After assembling an unlikely crew, piloted by a visually impaired captain, and with catering by an alcoholic cook, Fitzcarraldo sets forth on his audacious and somewhat improbable expedition.

Fitzcarraldo: As true as I am standing here, one day I shall bring grand opera to Iquitos. I will outgut you. I will outnumber you. I will outbillion you. I will outrubber you. I will outperform you. Sir, the reality of your world is nothing more than a rotten caricature of great opera.

This quest plays out over the next two hours as the crew encounter a number of hurdles, from internal conflict aboard ship, to desertions, and of course, tricky encounters with the local tribesmen. Herzog’s mastery of cinematic technique is on full display as the steamboat creeps down the river, the measured camera movements effectively mirror the sense of unease within the crew. Perhaps most impressive is the extended shot of the steamboat being dragged up the hill. Rather than using fast cuts to dramatise this shot, the camera stays fixed to allow viewers to fully witness the spectacle. As Kinski states:

We are going to drag that ship over the mountain like the cow jumped over the moon.

There are no camera tricks or model boats at play here, the realism lends the sequence an almost documentary quality.

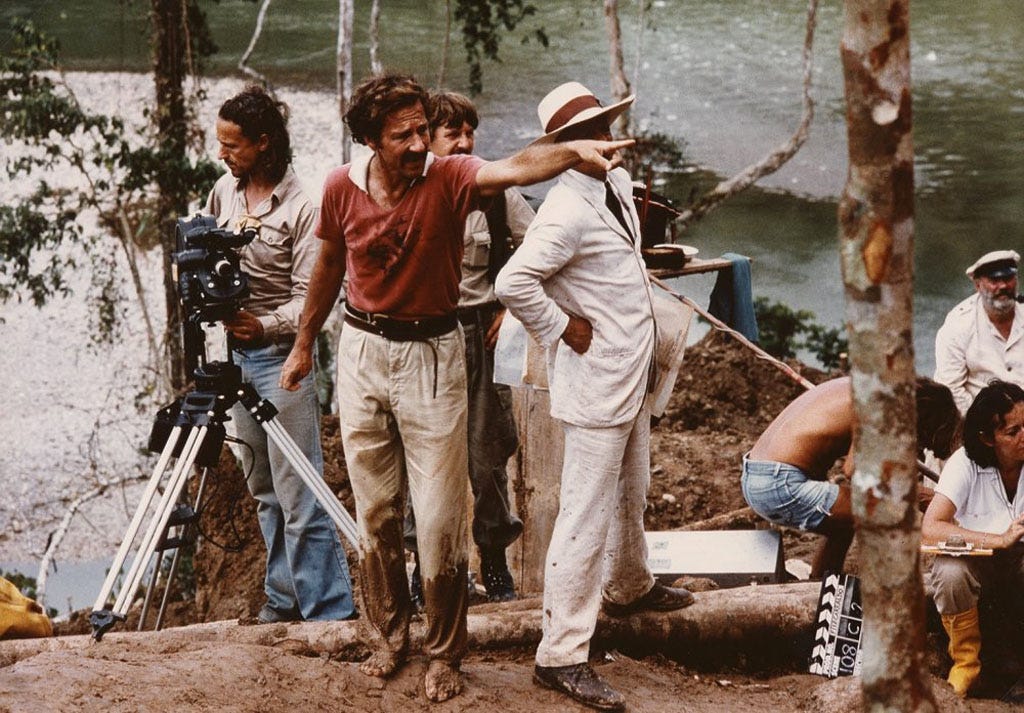

The fascination with the film extends beyond the perilous adventure of Fitzcarraldo himself, with Herzog’s own four-year ordeal in making it. Filmed in the rainforest hundreds of miles from the nearest city of note, the production faced hardships, including two plane crashes, drownings, chronic illness, and a particularly gruesome incident involving a crew member amputating his own foot with a chainsaw following a bite by a venomous snake.

This isn’t even to mention the turbulent relationship between Herzog and Kinski. Some may argue that the controversies surrounding the film are as interesting as what’s happening on screen, made clear by the critical acclaim of the documentary Burden of Dreams, which delves into the film’s troublesome production. While fascinating, these events raise questions about the ethics of Herzog's methods here: elaborate set pieces went ahead despite warnings and safety guidance from the on-set engineers.

Ship’s cook: Those bare-asses have never heard music like that. That will teach them to respect us.

[just as an arrow narrowly misses his head]

There is certainly something uncomfortable about the romanticising of a brutally exploitative era – the inherent violence is notably absent from Herzog’s portrayal. As Fitzcarraldo drags indigenous workers into peril for his dream, Herzog was arguably doing the same just for the sake of his film – an unsettling parallel. Fitzcarraldo is portrayed as a man of wild ambition and grand delusion. When his dreams collapse as his steamboat tumbles and tosses through the rapids, we feel empathy, a sentiment never afforded to Aguirre. His goal of bringing opera to the heart of the Amazon sounds innocuous. Yet, can we truly admire a character who imposes his cultural ideals on others without any real attempt at engagement or mutual understanding? Is this not merely another form of colonialism?

His form of colonialism is more insidious as it comes under some twisted noble pretensions - C

Whether you think Herzog a maniacal director propagating questionable ideals, or a master of his craft, he undeniably presents a challenge to the audience. What is the true cost of artistic endeavour? As the film twists and turns through its loosely formed near three hour runtime, Kinski captivates with his intensity, deftly able to add authenticity to Fitzcarraldo’s wild ambitions and passion that perhaps with any other actor would seem implausible and absurd. Despite ultimately having to settle for a lesser victory when his plans unravel amid the harsh conditions of the Amazon, he demonstrates that great feats are achievable through determination – though we are also reminded that such feats inevitably carry grave costs.

A madcap blend of Icarus and Don Quixote – Werner Herzog, Klaus Kinski, or both? – S

Reids’ Results (out of 100)

C - 69

T - 71

N - 78

S - 72

Thank you for reading Reids on Film. If you enjoyed our review please share with a friend and do leave a comment.

Coming next… Dreams(1990)

Hello Reids On Film. Intrigued to read your review. I saw this last year at the cinema having seen it on those tiny telly's from our youth (S). My Dad, a Herzog fan, talked of this and Aguirre, the Wrath of God, growing up. 'The making of', documentary does inhabit the watching but adds to the myth of Kinski. Unimaginable to consider another actor as lead. On 2nd viewing and a good few decades apart, the ending surprised me most. Originally, for me, it felt a bit corny and perhaps not prepared for his failure, I was disappointed. Now, it feels triumphant and joyous, stood atop his listing boat, cigar and hat while opera is performed. Agree with N - high 70's