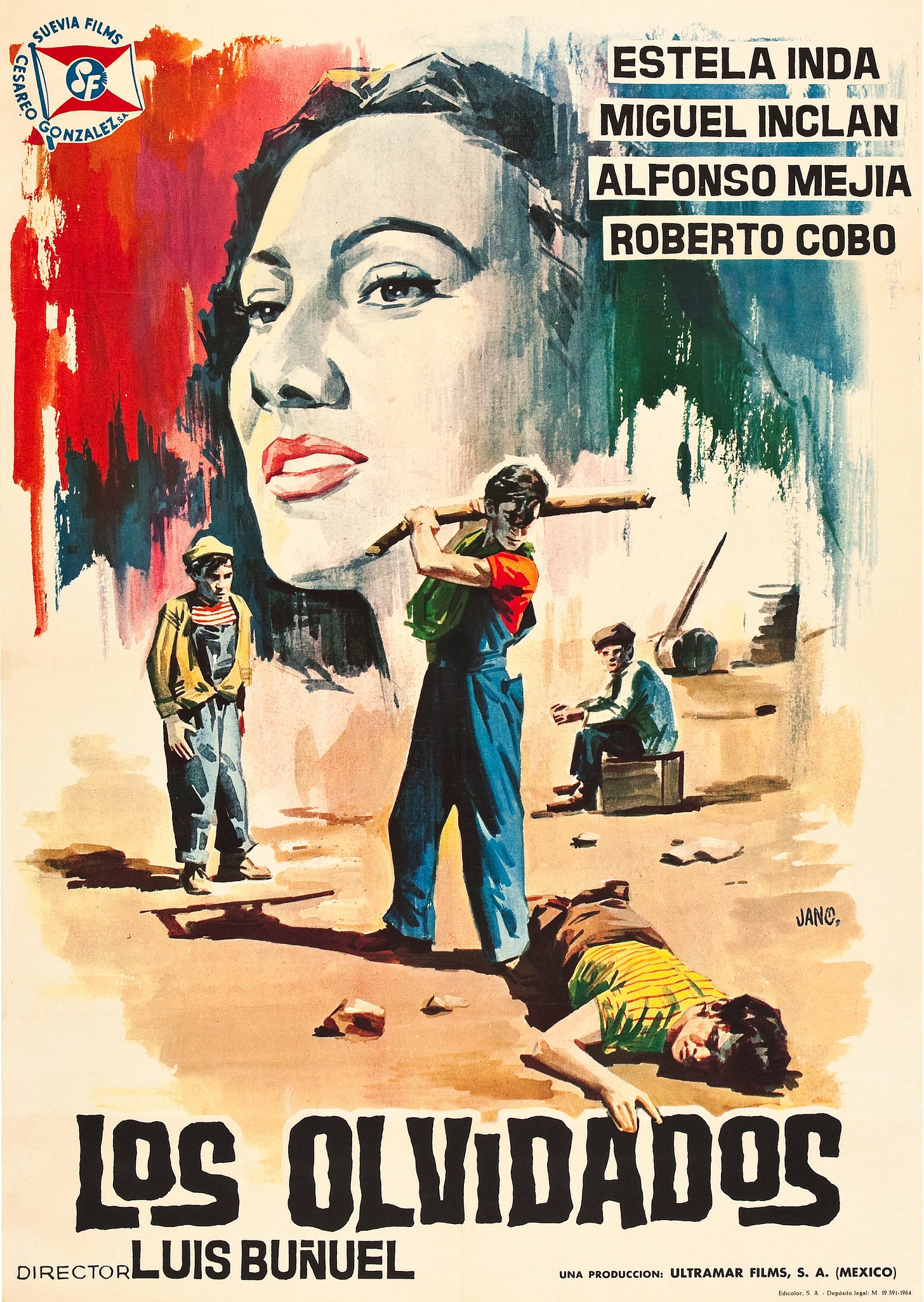

Directed by Luis Buñuel

Mexico, 1950

A few weeks ago one of ReidsonFilm took a trip to Mexico where they were recommended this week’s film by a local guide. What made the film unique, according to the guide, was that it ventured to offer an honest portrayal of Mexico.

Mexican cinemagoers, he said, were used to seeing melodramas which depicted the pervasiveness of love in spite of hardship: “We may be poor … but at least we have love.” While perhaps comforting, these films didn’t reflect the reality that many Mexicans faced during the so-called ‘Mexican miracle’, a period of economic growth beginning in the 1940s that in fact left many of the working class behind.

Luis Buñuel’s Los Olvidados, literally ‘The Forgotten Ones’, confronts this reality in an unapologetic and, at times, brutal fashion. As relative newcomers to the world of Mexican cinema, ReidsonFilm were seriously impressed.

The film begins by setting a typical coming-of-age scene. We meet a gang of rag tag youths, not dissimilar to Fagin’s boys or some other Dickensian ne’er-do-wells, playing in the streets of Mexico City. We immediately get a sense of Buñuel’s eye for style and camerawork through the mock bullfighting game the youngsters play. The camera cuts back and forth between the ‘bull’ and the ‘matador’ echoing the physical theatrics of silent-era cinema.

This harmless tomfoolery escalates however, upon the arrival of El Jaibo (Roberto Cobo) the gang’s leader, recently escaped from juvenile detention. Jaibo quickly co-opts the group into more menacing endeavours, getting them to rob a blind street musician and then assaulting a disabled man. There is a nastiness in Jaibo’s behaviour which far exceeds anything you’d expect from the Artful Dodger, and he immediately establishes himself as an unlikeable antagonist

As Jaibo ingratiates himself further into the group, he focuses his attention on Pedro (Alfonso Mejia) a young boy living in the streets, estranged from his mother and siblings. Pedro is taken down a much darker path when Jaibo involves him in a particularly vicious crime, which immediately leaves a traumatic imprint. The film then proceeds to follow Pedro as he treads a fine line between innocence and corruption, striving to find redemption after his involvement in Jaibo’s transgression.

There are moments in the film that bring to mind classic Italian neorealist works such as Bicycle Thieves. Los Olvidados is a stark exploration of poverty, violence, and the human condition at its purest. Where Buñuel is unique however, is that he seems to offer hope and resolution, a chance at redemption, before immediately snuffing it out. His refusal to provide easy solutions mirrors the harsh realities faced by the characters, and the impact is nothing short of haunting. The final shot of the film in particular stands out as a shocking testament to the brilliance of Buñuel’s approach.

Whilst dealing predominantly in gritty realism, Buñuel is also confident stepping into the realms of fantasy, surrealism and disruptive cinema - typified by a moment when Pedro throws an egg directly at the camera. This egging of the fourth wall acts as a sharp rebuke to the voyeuristic nature of documentary cinema.

Perhaps best known for his collaboration with Salvador Dali on Un chien andalou Buñuel draws on his background in surrealism to delve into Pedro’s inner turmoil during an extended dream sequence. When his mother (Estela Inda) appears in the dream, the scene is undoubtedly in dialogue with Freud, hinting at Jaibo as Pedro’s id: we go on to see an intimate relationship develop between Jaibo and Pedro’s mother.

It should be clear by now that Los Olvidados doesn't shy away from portraying its characters as either flawed or just outright unlikeable. Those who initially seem sympathetic are revealed to be just as selfish as everyone else. Even seemingly compassionate figures, like the warden of the juvenile facility, ultimately fail Pedro. The absence of pathos in the film's narrative is a testament to Buñuel's unapologetic approach, exposing the horrors of poverty without any gloss or sentimentality. It's also worth noting that Los Olvidados faced a backlash from the Mexican critics but then went on to gain recognition after a screening at Cannes: acclaimed for its subversive narrative and departure from typical tropes of Mexican cinema. The film broke new ground and opened doors for a more honest and unflinching depiction of socioeconomic discontent. As such, it earns its place among some of the great artistic portrayals of misguided youth, whether that be the novels of Charles Dickens, the dystopian droogs of Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange, or the streets of Compton in Kendrick Lamar’s seminal album good kid, m.A.A.d city.

I hope they’ll kill every one of them before they born!

A final thought on the duality of the film’s titles: the original in Spanish ‘The Forgotten Ones’ and the later English ‘The Young and the Damned’ create an interesting dynamic around the central question of the film. Can these characters be redeemed? The former title offers us an explanation - these boys were forgotten, abandoned and ultimately failed by society. In contrast the English title’s condemnation points to an inherent evil, in a ruthless and remorseless character such as Jaibo, who seems the embodiment of the Original Sin. Buñuel refuses to answer this question for us.

Reids’ Results (out of 100)

C - 80

T - 83

N - 78

S - 88

Thank you for reading Reids on Film. If you enjoyed our review please share with a friend and do leave a comment.

No review next week but we will return on 5th June with a double bill, of which more details later…