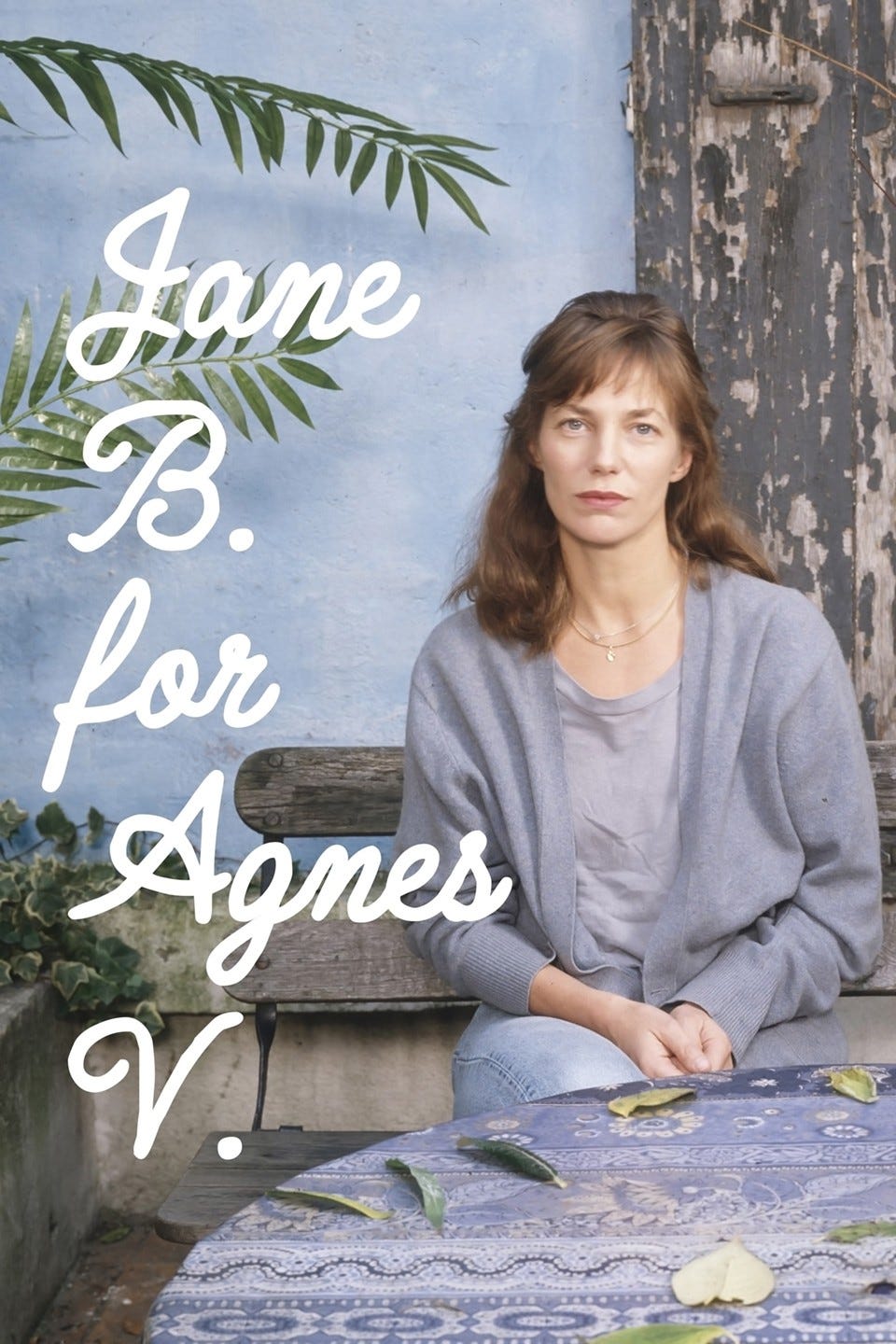

Directed by Agnès Varda

France, 1988

This is a brief reminder that ReidsonRecord, our carefully curated playlist, now hosts three hours of the best film music. The perfect accompaniment for your listening while on a car journey, baking some bread, running a 10K - or even a marathon if you’re quick. The link follows this review.

This week’s film opens with a tableau vivant: two women, one seated, in medieval costume. Another woman stands nude in the corner. A female narrator reminds us that time is ever passing, drop by drop, each minute, each second. And then the seated woman begins to reminisce about spending her 30th birthday alone in London while shooting a film. Sitting in her hotel room, she drank a bottle of sweet sherry. She crawled to the bathroom and vomited in the toilet. A pair of socks was hanging on a rack and she used them to wipe her mouth. Looking at her red face in the mirror, she said, “Shit! So this is 30.”

This is Jane Birkin: actor, singer, daughter of a British Naval officer. When she died last year Emmanuel Macron, the President of France, called her a French icon. Birkin is best known for her sensational film debut in Antonioni’s 60s classic Blow-Up and then there was J’taime moi non plus, an erotic duet with her partner, Serge Gainsbourg. The song was so notorious that it was banned in several countries, and even denounced by the Pope.

Starting out as a fashion model and widely regarded as a director’s muse, there is perhaps too little appreciation of her work in cinema – she appeared in over 70 films. Someone who did recognise her screen presence was the French New Wave director, Agnès Varda, and in 1988 they collaborated on Jane B. par Agnès V., which they both described as an imaginary biopic.

Of all the French New Wave directors I think Agnès Varda was the greatest. She played with time and memory in her work in a way that fundamentally changed cinema but wore her learning so lightly. She never felt the need to show off – S

Jane B. par Agnès V. is a fascinating docudrama or drama documentary – you’re never quite sure which. After that opening scene the pair meet in the café and talk about Birkin’s experiences in cinema, how she related to different directors, what she thought of her own performances, and significantly, her fear of the intimacy of the camera.

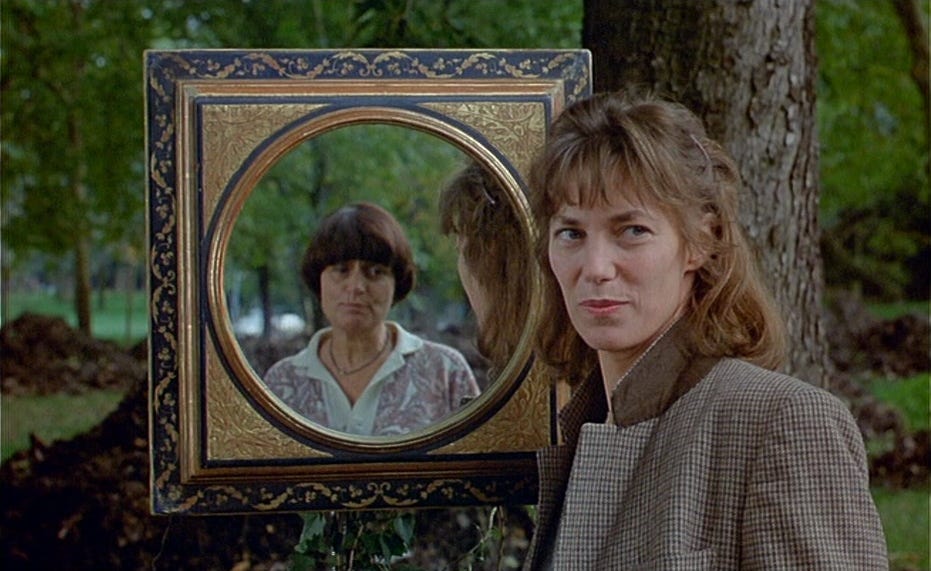

Varda: I’m filming your self-portrait. But you won’t be alone in the mirror. There will be the camera, it’s a bit me. Too bad if I appear in the mirror or the background.

What then unfolds is a series of episodes of Birkin talking about her childhood and life off-camera, interweaved with vignettes where she plays various renowned Janes from history: Calamity Jane, Tarzan’s Jane, and Jeanne d’Arc. Like a series of playful screen tests, both actor and director explore different roles, including a surprising and revelatory take by Birkin in her playing of Oliver Hardy of all people, in a Laurel and Hardy tribute.

Coming back to that bottle of sweet sherry, one focus of the film is Jane Birkin’s fear of reaching 40, and losing her beauty. Well Varda is having none of it here. Birkin gets to try out those parts which now she would presumably be considered too old for, but placed alongside the reflections on her private life, we gain an insight into the many roles she has played as a woman: actor, singer, muse, and mother to young children.

...it’s like an interesting reflection on her two primary roles in parallel, a dialogue between womanhood and woman as presented through cinema – C

Jane B. par Agnès V. is a film of dialogue and duality: actor and filmmaker, Britain and France, artist and agent, foreground and background. And ultimately, order versus chaos, because although there is a structure to the film, Varda allows Birkin to create chaos and suddenly it changes direction. Perhaps this sounds self-indulgent, but it’s testament to Vardar’s willingness and ability to experiment, and deftly switch between genres and ideas that this work never comes across as pretentious.

Hopping across the line between fact and fiction is a thread that runs through Varda’s filmography, and here she combines that playfulness with a surreal touch by casting Birkin as figures from classical paintings that gradually come to life: works by Magritte and Goya feature before we are presented with Birkin as Manet’s Olympia, who suddenly becomes enveloped in a swarm of flies. Varda casually shrugs off the rules defining cinema, just as she shrugs off the rules defining womanhood. And she is just as much a subject of this film as Birkin. Her face appears throughout – in mirrors, holding the camera – and then is there is a reveal…

Birkin is once again bemoaning the restrictive trappings of celebrity and Varda labels her the Queen of Paradox: seeking stardom and yet wanting to be treated as a nondescript person, a famous nobody. Varda then recounts direct to camera the story of L'Inconnue de la Seine, The Unknown Woman of the Seine. The corpse of an anonymous woman was found in the river. Suspected of suicide, she was so beautiful that a death mask was made of her face. Her enigmatic smile was compared to that of the Mona Lisa, and the figure became so popular that many copies were made. Varda bought one herself, but wonders whether this woman had been happy when she killed herself or had a worker in the morgue forced her mouth into a smile just for the purpose of the mask? Are people simply projecting their fantasies onto her face?

Varda: she was a nobody who was a somebody. I wonder if the only true portrait is a death mask.

I’ll look at you but not at the camera. It could be a trap - Jane Birkin

Reids’ Results (out of 100)

C - 75

T - 74

N - tbc

S - 73

Thank you for reading Reids on Film. If you enjoyed this review please share with a friend and do leave a comment.

And here’s that ReidsonRecord playlist:

Coming next… The Black Hole(1979)