Directed by Chantal Ackerman

Belgium & France, 1975

It was with some trepidation that ReidsonFilm approached this film. Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles – to give it its full title – topped the 2022 Sight and Sound and British Film Institute poll of the ‘Greatest Films of All Time’. Held once a decade, it took the No.1 slot from Hitchcock’s Vertigo and joined the ranks of previous winners: Citizen Kane and Bicycle Thieves. Sounds really promising, and yet Jeanne Dielman runs almost three and a half hours and has a reputation for being one of those films in which ‘not much happens’. However, ReidsonFilm are nothing if not adventurous in our cinematic choices – we are, after all, the team that sat through every minute of El Topo.

Written and directed by the late Belgian filmmaker Chantal Ackerman, Jeanne Dielman is undeniably a rigorous and challenging watch. The setting is Brussels in the mid-1970s, a time immediately recognisable from the desaturated, muted colours – greys, oranges, beiges – and the pattern-heavy wallpaper and curtains. An atmosphere that today’s production designers spend a lot of time and money to recreate (see Tomas Alfredson’s Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy).

This is a film that documents the life of the title character over three days. I say documents because Jeanne Dielman is shot with a fixed, static camera. The takes are minutes in length and there are no quick edits. Most of the ‘action’ takes place within the confines of Jeanne’s modest apartment. She is an everyday woman, a widow – although she confides that her marriage wasn’t a happy one – and now, a single mother to her adolescent son, Sylvain. Money is short – every time she leaves a room, even for the briefest moment, she switches off the light. And that is the premise…

For three days we watch as Jeanne carries out her household tasks, seemingly on a schedule. She wakes Sylvain and gets him ready for school. She washes the dishes, cleans the apartment, leaves briefly to pay her bills and do some shopping. When she gets home, she cooks – always meat and potatoes it seems. Much of her work is of the humdrum sort that few people have the inclination for today – when did you last polish your shoes on a kitchen table covered with old newspaper? That has certainly slipped through the generational cracks in the ReidsonFilm household. As Jeanne sits for a moment of respite at the living room table, she writes a letter to her Canadian relatives on that long-lost thin, blue airmail paper. She is shot mid-frame and, in the background, a blue neon light – perhaps, from a neighbouring shop – flashes continually, reflecting on a glass-front cabinet. Just as you are wondering the significance of this – is it ominous? – the doorbell rings.

A man, grey and non-descript, has arrived. No words are exchanged as they go into Jeanne’s bedroom, and she closes the door. We assume they are having sex. We don’t see it happen, but she has laid a towel on the bed and when they emerge, the man gives her some money and says he will return next week. Jeanne puts the money in a porcelain tureen on the dinner table and replaces the lid. She takes a bath and then she scrubs the bath, and so her day continues.

The sex appears to be as routine as her other jobs. When Sylvain comes home from school, they silently eat dinner, go for a brief walk, and then he sleeps on a pull-out bed in the living room. There is something odd about Sylvain (Jan Decorte). He has the lanky, awkward appearance of adolescence, but he also looks as though he should have left school at least five years ago. Constantly reading, he does little to help at home. He rarely has a conversation with his mother but does have some rather eccentric ideas about sex which he is only too happy to share.

And that is one day, a day that will be repeated three times. The only variation is that a different man arrives each afternoon. Is Jeanne Dielman boring? At moments, certainly, although there are plenty of shorter, so-called action films in which I have been bored throughout. What Jeanne Dielman presents are the events that cinema usually omits or elides. A watched kettle does boil… eventually. Jeanne’s repetitive toil has a ritualistic form that borders on the obsessional. Is this a film about control and making choices? Or is that an illusion? As your attention wanders you begin to project your own ideas onto Jeanne’s story and motives. Who is this woman, really?

But do stick with it, because although the days are repetitive you will start to notice things change, small slips in her routine… errors, forgetfulness. Cracks begin to appear. Jeanne polishes her son’s shoes and loses the brush; she puts her money in the tureen but forgets to replace the lid. And horror of horrors, she overcooks the potatoes! This event sends her into a brief panic. She wanders the apartment, from room to room, holding the pot of potatoes. For a moment, it appears that she might dump them in the bath. She comes to her senses and puts them in the bin. Yet, something has changed. Even Sylvain notices that she is different. Slowly, that sense of boredom, ennui, evolves into something else, a feeling of dread.

Jeanne Dielman is a film in which nothing is hidden. Everything is on screen, except of course when the doorbell rings and Jeanne closes her bedroom door. And yet, I find it hard to recall a film laden with so much ambiguity. We witness a mysterious performance, enigmatic but also paradoxically revealing, by Delphine Seyrig. An unusual and unexpected choice for the lead role given that Seyrig was a recognisable star. She played ‘A – a beautiful woman’ in Alain Renais’s Last Year at Marienbad, and despite her dressed-down casting she is nonetheless a magnetic presence.

In a similar vein, the ending of Jeanne Dielman, when it comes, is not what you would predict, but at the same time feels inevitable. So, is this film a masterpiece of feminist cinema? Perhaps, but Jeanne Dielman may also be one the great existential thrillers. The history of cinema celebrates some outstanding long takes. Think of the opening crane shot in Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil, or Scorsese tracking Ray Liotta through the back of the Copacabana club in Goodfellas. Well, with Jeanne Dielman we have a static camera watching her peeling potatoes, which I found just as compelling. It lasted for eight minutes.

The greatest film of all time? Well, that’s a ridiculous question when we know that the correct answer is Mulholland Drive. But Jeanne Dielman may speak to you in a way that few films ever manage.

Like I can see why it’s loved, it is a groundbreaking piece of film, shot perfectly, acting is excellent the subtle moments. So yeah is it radical art? Yes. did it ‘work’? Yes. Did I enjoy it? No. Will I watch it again? Almost definitely not - C

Reids’ Results (out of 100)

C - 70

T - 76

N - 79

S - 87

Those generational cracks again, but thank you for reading Reids on Film. If you enjoyed our review please share with a friend and do leave a comment.

Jeanne Dielman now enters the ReidsonFilm Pantheon of Slow Cinema

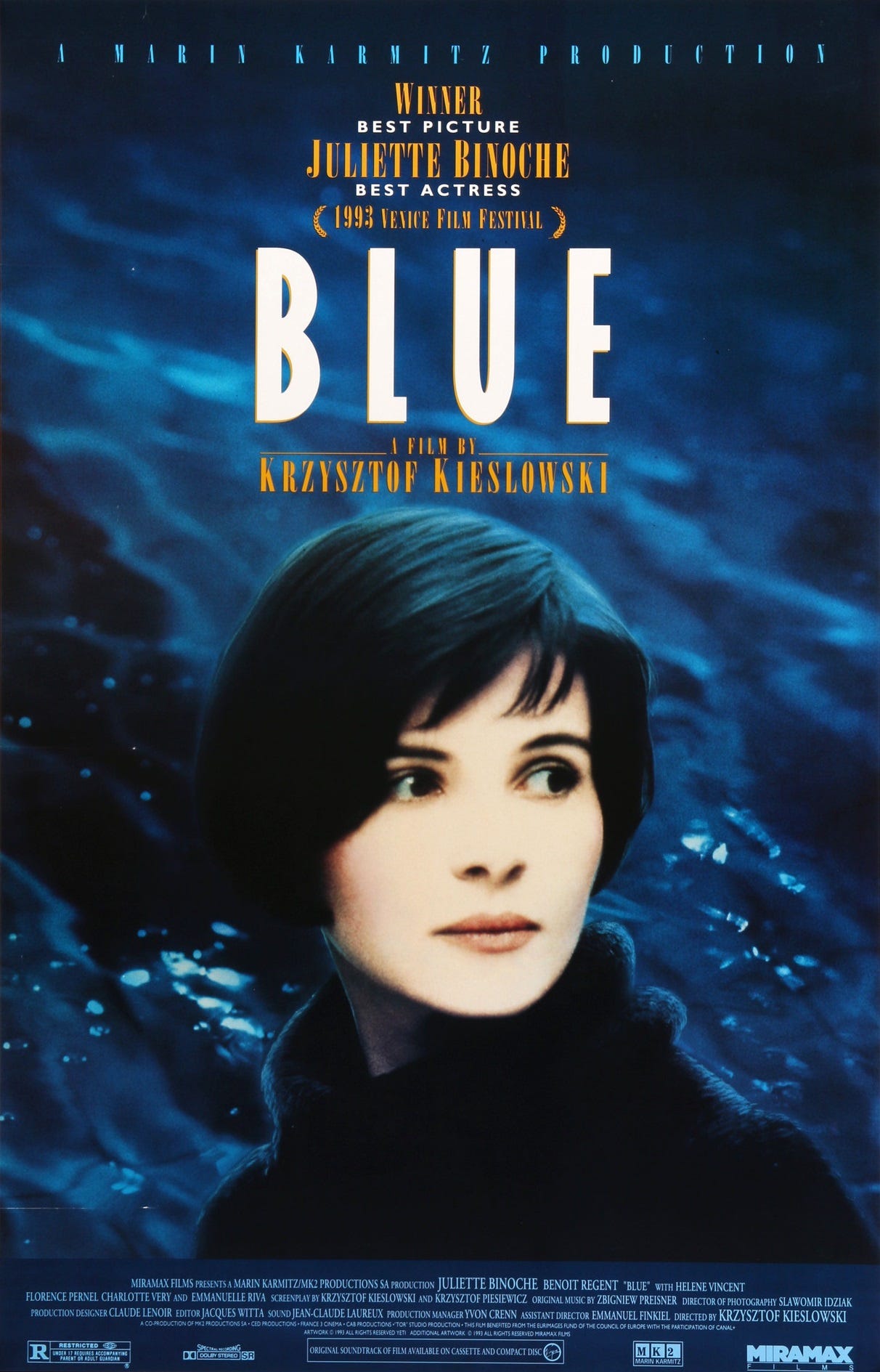

Coming next… Three Colours: Blue(1993)