Directed by Hiroyuki Okiura

Japan, 1999

So Jin-Roh, this week’s film, is an anime. “Do you mean a cartoon?”, we hear some of you ask. Well yes, an anime is an animated film, either hand-drawn or computer-generated, and has a rich Japanese history dating back to 1917. Of course the films from Studio Ghibli will be familiar to many: Spirited Away, My Neighbour Totoro, Howl’s Moving Castle.

Much of the anime we have seen is either fantasy or science fiction but Jin-Roh gives us something different. You could describe it as speculative fiction, but there is nothing in the narrative that goes beyond the realm of reality. The speculation comes with the prologue, which gives us an alternative modern history of Japan set in the years after World War II. Japan has been occupied by a victorious Nazi Germany.

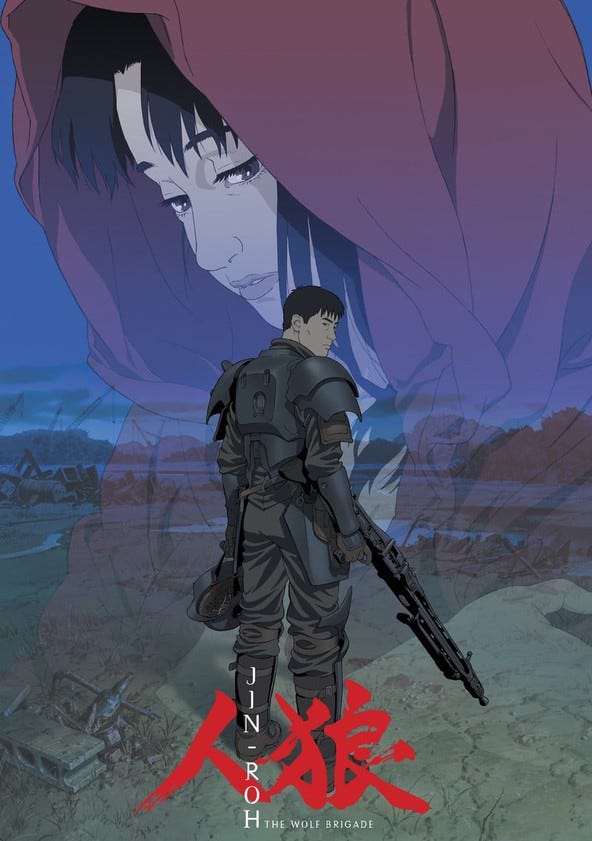

Following the Germans’ departure Japan shoots off on a path of rapid economic growth, accompanied by a widening divide between the haves and have nots. An atmosphere of growing unrest and increasingly violent protests are too much to handle for the local police, so a specialist anti-terror unit is brought in: the elite Kerberos Panzer Corps, a paramilitary outfit bearing body armour, gas masks, demonic red night-vision goggles, and of course very big guns. Also controversially, they operate outside of the parameters of the police hierarchy.

Kerberos (Cerebrus): Greek mythology, a three-headed dog guarding the entrance to the underworld

The film opens with a riot, and a Kerberos squad tracking a group of protesters in the sewers beneath the streets. One of this group has thrown a napalm-laced Molotov cocktail into the ranks of the police. A Kerberos officer corners a young woman who has been ferrying bombs to the protesters and is ordered to shoot her. He hesitates and she detonates one of her bombs, blowing herself up. He removes his mask, revealing himself as human. His name is Kazuki Fusé. At this point, you might be thinking this is a generic action movie – but no, what follows is a thoughtful, considered, and at times unsettling exploration of the relationship between the person and the state, politics and the personal, and of course the dehumanizing experience of living in a state of oppression.

We're not men disguised as mere dogs. We are wolves disguised as men.

Jin-Roh was written by the filmmaker Mamoru Oshii, the director of Ghost in the Shell, but this film is directed by Hiroyuki Okiura. The tagline ‘The Wolf Brigade’ is apt as they use the story of Little Red Riding Hood as a parallel allegorical fable to ask the question: who is the human and who is the beast? A challenge not only to the lead characters, but also to the audience. The rebels (or terrorists) regularly use women and children to carry their weapons and the slang term for them is ‘Little Red Riding Hood’. Of course the version we see here is the original Grimm Brothers version – red in tooth and claw.

Fusé, traumatised by the death of what was, in essence, a suicide bomber struggles to make sense of his hesitancy. His self-image shifts from that of a wolf to that of a man in his dreams as well as reality. And then, in a nod to Hitchcock’s Vertigo, Fusé falls for the near identical, apparent older sister of the dead girl. But could she actually be a wolf in disguise?

The pursuit of a girl in a red coat through the sewers and catacombs of a city: Don’t Look Now? – S

Jin-Roh is a film of many layers and certainly bears repeated viewings. The hand-drawn artwork makes a striking contrast with contemporary, and often tired, CGI. The artists have used a muted colour palette with earthy tones that along with the haunting and poignant strings-based score, gives the film a world-weary sense of ennui. In fact, Jin-Roh brings to mind the classic film treatment of John le Carré’s espionage novel, The Spy Who Came in From the Cold with a tired and hard-bitten Richard Burton.

The film has some breathtakingly cinematic moments. In the riot scenes at the start, with the protesters battling the police, the frames are packed with detail and the expressionist artwork gives a sense of real depth. This contrasts with the later dream sequences where we switch to the fast-cutting 2D images more typical of an anime. Okiura takes his time in telling the story, allowing some shots to linger, but with a running time of 100 minutes Jin-Roh never outstays its welcome.

What we are watching is clearly an anti-authoritarian film. But Okiura does not glamourise the rebels: the message is more ‘a plague on both your houses’. When Jin-Roh was released in 1999, Japan was coming to the end of the first of its ‘Lost Decades’, a period of economic collapse, and that year the country suffered the Tokaimura accident, Japan’s worst nuclear disaster until Fukushima 12 years later. Perhaps that is why Jin-Roh wasn’t made as a live action film. Was it just too close to reality? What we have here however is an anime (or cartoon if you like) that demonstrates that art can indeed come close to the truth.

The hunters kill the wolves in the end only in the tales humans tell.

Reids’ Results (out of 100)

C - 72

T - 76

N - 74

S - 78

Thank you for reading Reids on Film. If you enjoyed this review, send it to a friend and do leave a comment.

Coming next… Hagazussa (2017)