Directed by Mathieu Kassovitz

France, 1995

So, ReidsonFilm return for a 4th season and we begin with a French film from 1995, La Haine. Its incendiary title translates as ‘hatred’, and the film’s visual epigraph is a shot of a Molotov cocktail hurtling through space towards Earth. The four-minute credit sequence has the Wailer’s song ‘Burnin’ and Lootin’,’ playing against documentary footage of rioters clashing with the French police.

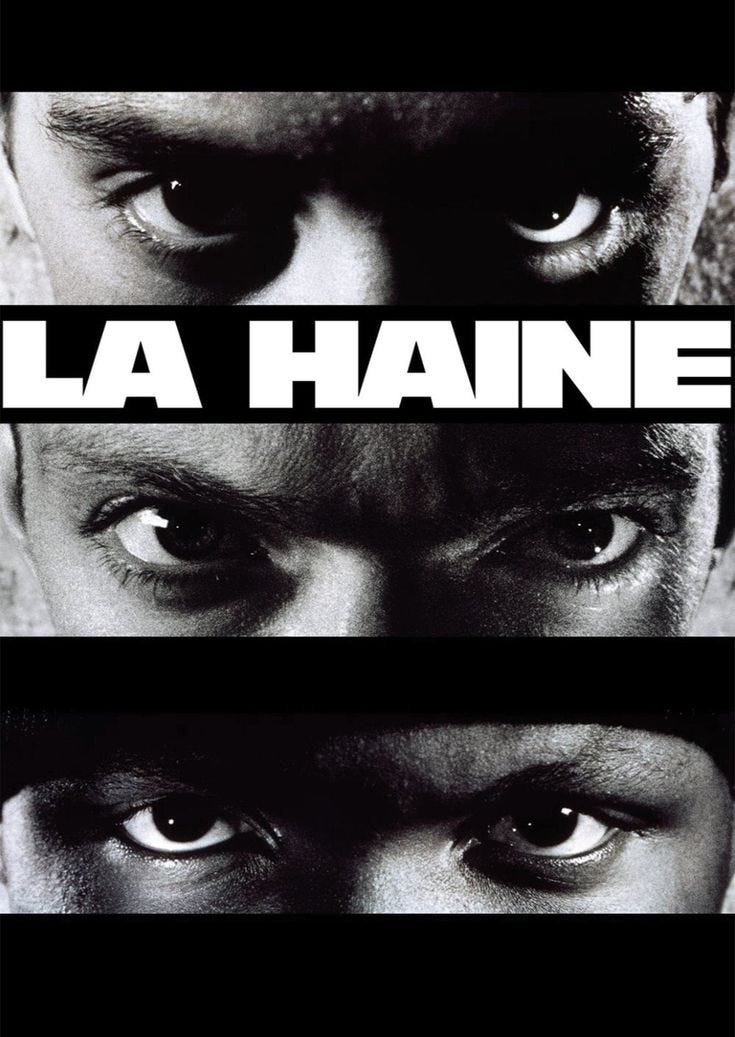

And yet this angry outburst of a drama by debut filmmaker Mathieu Kassovitz also has moments of humour and affection shared by its three protagonists: Vinz, Saïd, and Hubert. In what sounds like a contrived set-up for a joke – a Jew, an Arab, and a black man walk into a bar – our three heroes are young men living in the oppressive Parisian banlieues, the suburban housing projects that ring the city. Following the hospitalisation of their friend, Abdel, after a brutal beating in police custody, riots erupt and a police station is attacked. What follows is, in essence, a day in the life of the trio. The regular timestamps and sound of a ticking clock – or is it a bomb? – give the narrative a propulsive drive.

Of the three, Vinz (Vincent Cassel) is the hot-head wanting to bring war to the police. At the start of the film, he mimics Travis Bickle from Taxi Driver – “You talking to me?” – pointing at his bathroom mirror with an imaginary pistol. Later, he discovers a lost police revolver and threatens to kill a cop if Abdel dies. Saïd (Saïd Taghmaoui), a North African Muslim, is full of jokes and bravura, and often cast as mediator between Vinz and Hubert. A small-time drug dealer, Hubert (Hubert Koundé) set up a boxing gym only to see it burned down in the riot. Unlike his friends, Hubert has aspirations: Vinz wants to smash the system, Hubert just wants to escape it. There we have it: the id, the ego, and the super ego.

La Haine has little in the way of plot. We follow the three through a series of vignettes as they wander around the heavily policed neighbourhood before heading into central Paris. The film owes much to Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing (1989): hip-hop infuses the language, the music, and the fashion. KRS-One’s ‘Sound of da Police’ is expertly mixed with Edith Piaf’s ‘Non, je ne regrette rien’ by the French DJ Cut Killer, and there’s a brief interlude from the action to catch some breakdancing.

Kassovitz veers away from the vibrant colour palette of Lee’s film by shooting La Haine in black and white, though the gritty themes of the film contrast with the polish of the composition. The stylised camerawork echoes the cool sheen of Bruce Weber’s photography and his ads for Calvin Klein underwear.

Pierre Aïm, the cinematographer, captures the banlieues with an ultra-wide lens, highlighting the dystopian, labyrinthine design of the built environment, but in Paris Centre he switches to a long lens. The faces of the three friends dominate the frame, and Hausmann’s boulevards blur into the background. This is not the City of Light we are used to. Kassovitz’s social commentary at times is hammered home with a mallet: I lost count of the number of times Vinz, Saïd, and Hubert walk past a poster showing the planet Earth with the accompanying slogan, ‘The World Belongs to You’.

All three actors deliver compelling, wholly believable performances as they stumble around town, gatecrashing an art gallery’s private view, then walking into a gang of neo-Nazi skinheads. The blistering, in-your-face antagonism of Vinz is set against the puppy dog playfulness of Saïd, and the cool self-assurance of Hubert. The question is, where is it all headed? Perhaps the film answers this with an ostensibly comic scene at its midpoint. The trio visit a public toilet where an elderly man comes out of a stall and declares, “there is nothing like a good shit”. He then tells them a story:

Man: I once had a friend called Grunwalski. We were sent to Siberia together. When you go to a Siberian work camp, you travel in a cattle car. You roll across icy steppes for days, without seeing a soul. You huddle to keep warm. But it's hard to relieve yourself, to take a shit, you can't do it on the train, and the only time the train stops is to take on water for the locomotive. But Grunwalski was shy, even when we bathed together, he got upset. I used to kid him about it. So, the train stops and everyone jumps out to shit on the tracks. I teased Grunwalski so much, that he went off on his own. The train starts moving, so everyone jumps on, but it waits for nobody. Grunwalski had a problem: he'd gone behind a bush, and was still shitting. So I see him come out from behind the bush, holding up his pants with his hands. He tries to catch up. I hold out my hand, but each time he reaches for it he lets go of his pants and they drop to his ankles. He pulls them up, starts running again, but they fall back down, when he reaches for me.

Saïd: Then what happened?

Man: Nothing. Grunwalksi froze to death…Goodbye.

An allegorical message about choices? Jump on the train and do something, or scrabble forever with your trousers? A later scene suggests that the train has already left them behind.

Watching La Haine you sense an inevitable momentum, as though the chain of events is inexorably driving toward a fateful conclusion. Is this a cautionary tale - a warning about the destructive consequences of cyclical violence and retributive justice? We anticipate that Vinz will surely meet his nemesis. Which is why when it arrives the film’s climax, watched over by giant wall murals depicting the poets Arthur Rimbaud and Charles Baudelaire, hits you like a sucker punch. In the world of La Haine there is no moral order and no redemption, even for those that do the right thing.

This morning I woke up in a curfew / O God, I was a prisoner too – Bob Marley

Reids’ Results (out of 100)

C - 74

T - 77

N - 79

S - 73

Thank you for reading Reids on Film. If you enjoyed our review please share with a friend and do leave a comment.

Coming next… Wild Strawberries(1957)

'La Haine' is one of France's best inequality movies. I put it on the same list as 'Divines' (2016), 'Les Misérables' (2019) and 'Athena' (2022).