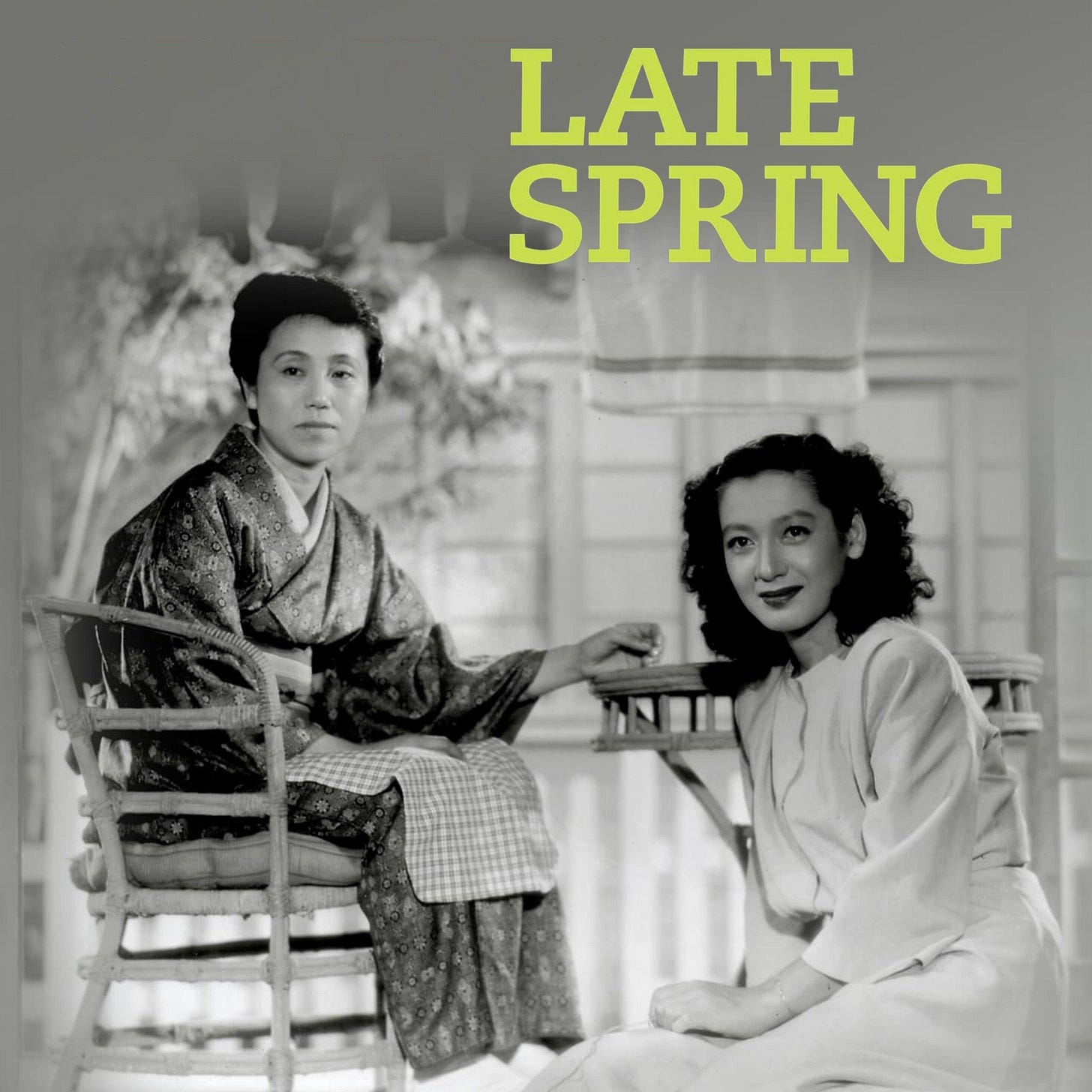

Directed by Yasujirō Ozu

Japan, 1949

Regarded as one of cinema’s greatest filmmakers, the Japanese director Yasujirō Ozu has a reputation as a minimalist for the simplicity of his narrative and the austere formality of his cinematography. Often though, this is used as a backhanded compliment as for some his films are too slow and the themes too repetitive.

It’s not only too slow, nothing happens … its a boring story - C

The same criticism could be made of the Impressionist artist Claude Monet: he painted 12 scenes of the Gare St-Lazare before moving onto haystacks, painting 30 of them. And then the paintings he is most well-known for, the waterlilies… 300 paintings. For Monet the subject of the painting was not so important perhaps, as capturing the play of light and colour over time. With Ozu, he isn’t so much telling a story, but painting a lyrical portrait. In that sense, he shares a lot with arguably the greatest novelist in the English language, Jane Austen, who wrote six books, in essence all telling the same story.

Late Spring (1949) is the first film of a series of domestic dramas and is considered the start of Ozu’s final creative period following a career that began with silent film. The plot is straightforward: set in a sleepy seaside town, a 27-year-old daughter, Noriko, lives happily with her father, Professor Shukichi Somiya, a widowed academic. Noriko’s aunt says that she needs to marry before she gets too old, but Noriko is reluctant. To force her hand her father pretends that he plans to remarry himself, so Noriko agrees and does get married. And that’s it.

But there is a richness and complexity to this film that rewards repeated viewing. A theme throughout Late Spring is the tension between traditional Japan and the modern world – old versus new, and East versus West. The film was made in 1949 when Japan was still under the American occupation following World War II. Oblique references are made to Noriko’s health after working in a labour camp, and the pressure to wed may in part relate to the shortage of available men.

When Noriko and her father visit Tokyo, they leave their village for the modernist new builds of the city. Roadside signs fly the flag for Coca-Cola and the Time & Life building oversees the cityscape – a monumental momento mori. This contrast between the past and the future is also played out at home. Noriko’s liberated friend Aya has recently divorced – only possible with the new Japanese constitution. She visits, and is greeted by Professor Somiya, who invites her to join him, sitting seiza-style on the floor. Before long she complains that her legs have gone to sleep. Noriko arrives and take her upstairs where they sit comfortably on Western furniture.

Of course, a Freudian analyst could, and probably would, make hay with their domestic situation. Noriko’s mother is dead so she has her father all to herself to look after, and in turn be looked after by him. What greater threat could there be than to bring a new woman into the house with all that conspicuous sexuality.

Noriko: I want us to stay as we are. I don't want to go anywhere. Being with you is enough for me. I'm happy just as I am. Even marriage couldn't make me any happier.

In one outspoken moment, Noriko tells her father’s colleague that he is ‘indecent and filthy’, solely because he has just remarried. And what to make of her comment to a male friend in a conversation about jealousy, “When I slice pickled radish, it comes out all strung together”.

The performance by the cast is captivating, but in particular the two Ozu stalwarts, Setsuko Hara and Chishū Ryū in the lead roles: a slight change of expression reveals a tremendous undercurrent of emotion.

I am large, I contain multitudes – Walt Whitman

As a director Ozu is renowned for his use of a static camera, often set low in the frame so it feels as if you are looking upward. And in dialogue scenes, the actors look straight at the camera while talking. This can take some getting used to. Theories abound about the reasons behind his methods. Is Ozu attempting to give us a truer human perspective on the family dynamics? Perhaps the explanation is more prosaic. In one of his earliest films the floor was in disarray because of entangled electrical cables: “Since it would take time and energy to tidy them up before shooting another shot,” the director said in an interview, “I turned my camera upward in order not to show the floor. I liked the composition and was able to save time as well. Since then, it has become a habit, and my camera has become positioned lower and lower.” Ozu often shoots frames – doors and windows – within frames, and the lack of camera movement means that every shot forms its own single composition.

I know it’s reductive to always compare Kurosawa to Ozu as the ‘only’ two Japanese directors people really talk about at length but in a Kurosawa film there’s always so much going on…the frame is bustling crowds are moving everywhere - C

I would argue that the same applies to Ozu...it's just that it's mostly implicit. And all done with a static camera. Genius - S

He also disrupts the narrative by cutting away to seemingly unrelated shots: a cloud scene, a single tree, a passing train. This gives us a sense of lived time, along with an elliptical editing style: purposely omitting scenes or incidents that seem important. We don’t see Noriko’s first meeting with Satake, her husband, to be. In fact, he never appears on screen – we miss the wedding.

Our final meeting with Noriko is a striking one. She is about to be married, has put away her western clothes and donned a beautiful, elaborate and traditional wedding dress. She kneels before her father:

Norika: You have been so good to me for so long. Thank you for everything.

Father: Be happy and be a good wife. Be happy.

Noriko looks up and forces a smile. They leave the house and we are left with a shot of the stool where she would always sit. A bittersweet ending? One of the reasons Late Spring is a masterpiece is that every viewer will come away with a different understanding of what has actually happened. The film ends with Professor Somiya sitting at home, alone, peeling an apple. The peel grows longer then drops on the floor. He bows his head… bereft.

I want to make people feel without resorting to drama. And it’s very difficult - Yasujirō Ozu

Reids’ Results (out of 100)

C - 69

T - 77

N - 75

S - 88

Thank you for reading Reids on Film. We hope you enjoyed our review and if you did please share with a friend and feel free to leave a comment.

Coming next… Divine Intervention(2002)

Glad that you saw the Austenesque aspects of this film, which a lot of people seem to miss (in favor of seeing the ending as ultimately tragic.)

One of my all-time favorite films.

If you're interested in an analysis of Ozu's style, the late, great David Bordwell wrote an excellent book on that topic.