Directed by Peter Brook

United Kingdom, 1967

The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton Under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade

Yes, this is the full title of this week’s film: an adaptation of the 1964 theatrical production of Peter Weiss’ play by the Royal Shakespeare Company. Alternatively, you could see Marat/Sade as a mashup of Les Misérables and One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest, but that would be to underplay the brilliance of this virtuoso take on the Terror of the French Revolution. Translated from the original German and directed by Peter Brook, that great shaman-showman of 20th Century theatre, this is a film of what is essentially a stage play, but somehow Brook makes it powerfully cinematic.

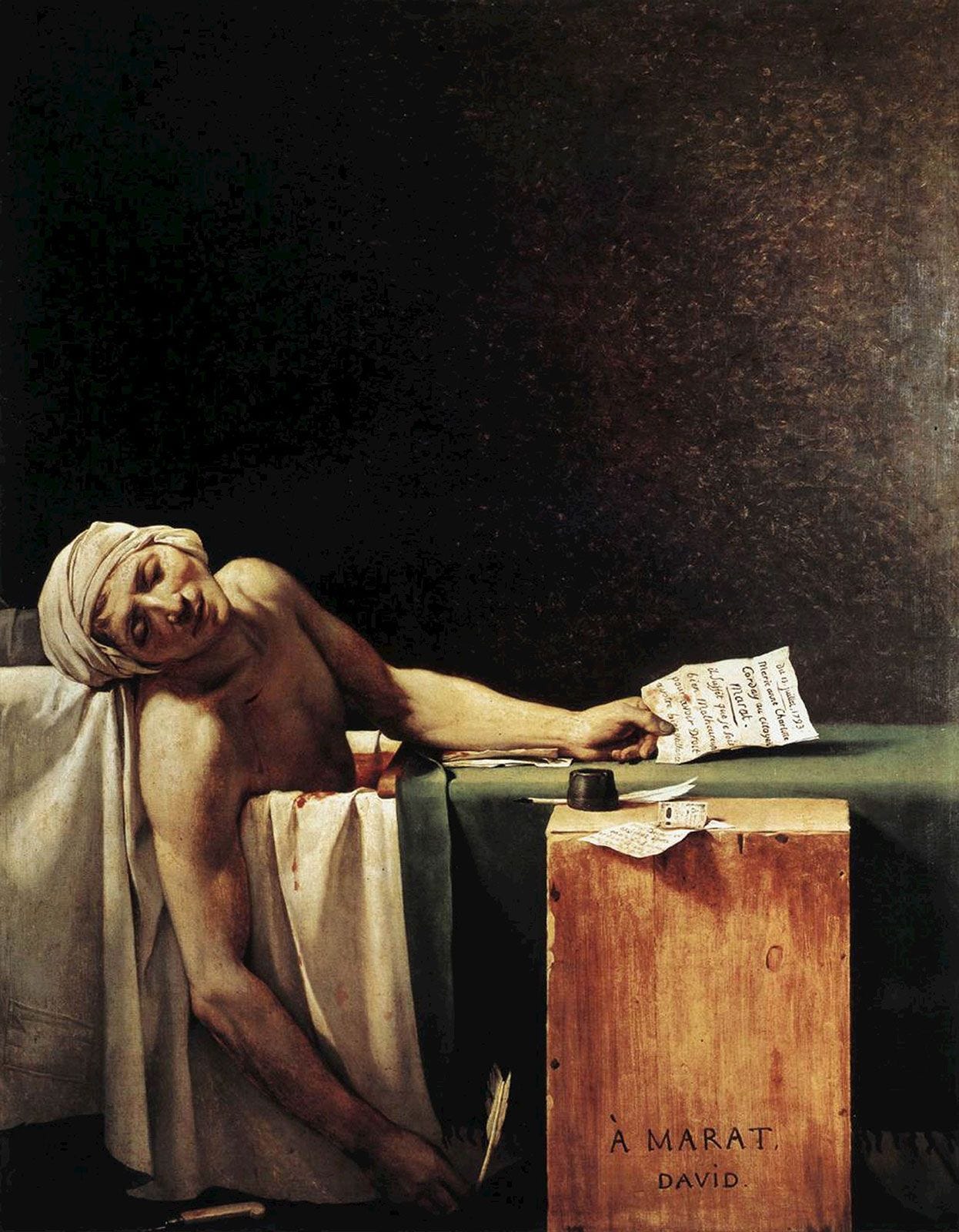

Mise en abyme: a term new to ReidsonFilm. In essence, a framing device where an artistic work refers to itself… a book within a book, a painting of a painting. Think of Hamlet, Mulholland Drive, and recent ReidsonFilm favourite, Synecdoche, New York. So, a film of a play about a play, Marat/Sade opens in 1808, fifteen years after the execution of Louis XVI, at the Charenton asylum, a psychiatric hospital just outside of Paris. The director of the asylum, François de Coulmier (Clifford Rose) introduces us to that night’s performance: a drama about the assassination of French revolutionary firebrand, Jean-Paul Marat, by Charlotte Corday.

The play is written and directed by the asylum’s most distinguished and notorious inmate, Donatien Alphonse François, better known as the Marquis de Sade. Perhaps unwisely, Coulmier brings his wife and daughter onto the performance space which is behind bars, though supposedly under the protection of the watching nuns and male ‘nurses’.

What follows is a dialogue played out through the drama, in which Marat and Sade debate the meaning and value of the Revolution. They were both early advocates of the Terror but disagree about where it went wrong, ending with the dictatorship of Napoleon. On the one hand we have Sade, the libertarian libertine who recognises the inherent flaws in man’s nature and embraces them. On the other, Marat, the idealistic Jacobin seeking the perfectibility of man. A clash between the idea of political murder as a spontaneous act of passionate liberation, set against the cold blade of the guillotine… Nietzsche versus Marx?

Although Sade had no particular problem with murder, he was an avowed opponent of the guillotine. To kill a man in passion was one thing, but to rationalise killing by law was a monstrous act. As he wrote:

Humans are governed by deep-seated desires far more than by any rational impetus. Nobility is a fraud. Cruelty is natural. Immorality is the only morality, vice the only virtue.

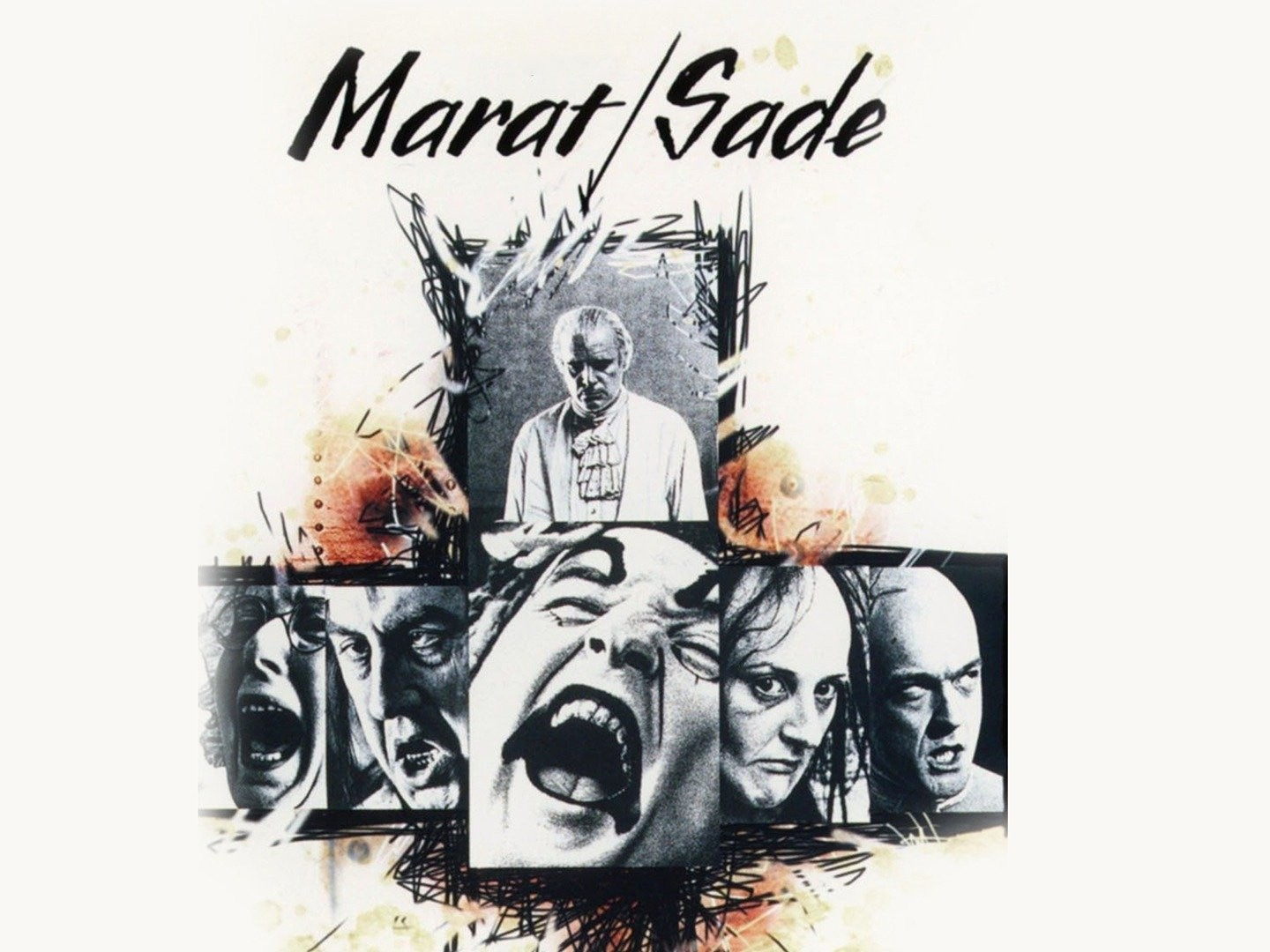

This may be starting to sound like a dry dialectic, but no, because what we are watching is a performance by the imprisoned inmates. Marat is played by a ‘paranoiac’, Corday, a depressed narcoleptic, who repeatedly needs to be woken up to speak her lines, and Sade? He plays himself of course… philosopher, or depraved pornographer? Well, that’s a debate for another time, but here as in real life Sade was permitted by Coulmier, the progressive director of the asylum, to stage plays for the public, casting his fellow patients. Coulmier considered this a form of therapy. As a consequence, we have a political critique translated through a series of maniacal outbursts, witty asides, and a droll musical commentary provided by a Greek chorus of clowns – foreshadowing the arrival of Wonka’s Oompa Loompas in 1971. But don’t be fooled, the arguments here are incisive and delivered with a caustic clarity.

The Marquis de Sade: if a man is imprisoned by Louis XVI, Robespierre, and Napoleon… can he have been that bad? - S

The action remains within a single room and on occasion we see the silhouette of an audience watching from the other side of the bars. Where Brook transforms Marat/Sade from the purely theatrical is in his use of the camera: it is freewheeling, closely following the actors, sometimes swooping into their faces. They break the fourth wall, with Marat and Sade frequently making their points direct to camera.

Unsurprisingly given their pedigree, the performance by the cast is captivating and masterful. Patrick McGee plays Sade, Ian Richardson is Marat, permanently ensconced in a bathtub to sooth his debilitating skin disease, and a previously little-known Glenda Jackson shines as Charlotte Corday. There are moments of Marat/Sade that are as enthralling as they are unsettling: the Marquis’ introduction, where he sits, staring directly at the camera, saying nothing; the construction of a guillotine on stage to reenact the King’s execution with blue blood flowing. Charenton’s supposedly enlightened approach to the treatment of mental illness is undercut by the use of waterboarding when the uniform call for liberation arises from the inmates. Freedom can only go so far.

And this then, is where Marat/Sade really becomes a film of consequence. The mise en abyme, the play within a play within a film, is not some cheap meta-gimmick, but a vehicle for the political crux of the film, exploring the relationship between power, madness and revolution. In the 1960s, when the spirit of revolution was again sweeping across Europe, Marat/Sade gave the audience an artificial distance from unfolding events, only to undermine this in the most Brechtian terms as the recreation of the violence begins to escalate. As the Herald narrates, sardonically:

Please remember that we show

only those things which happened long ago

Remember things were very different then

of course today we're all God-fearing men

Marat/Sade critiques the fragile notion that society can somehow replay the failings of the past as a demonstration of the civilised present. After all, as Peter Weiss wrote, the Charenton asylum was “an institution which catered for all whose behaviour had made them socially impossible, whether they were lunatics or not”. Those who do not conform, who do not support the Bonapartist regime, must be confined. And yet, in spite of the state-sanctioned violence used to contain them, the outbursts of the inmates as actors only get louder and begin to ring true.

The restricted space gives Marat/Sade a claustrophobic feel. Like a ticking time bomb, scene by scene the proceedings start to slip out of Coulmier’s control. Eventually, the revolution depicted in the play spills out into a real revolution on stage… and Sade stands back watching, laughing darkly.

Through Sade and Goya, the Western world received the possibility of transcending its reason in violence - Michel Foucault

Reids’ Results (out of 100)

C - 90

T - 81

N - 82

S - 89

Thank you for reading Reids on Film. If you enjoyed our review please share with a friend, and do leave a comment.

Coming next… Priscilla(2023)