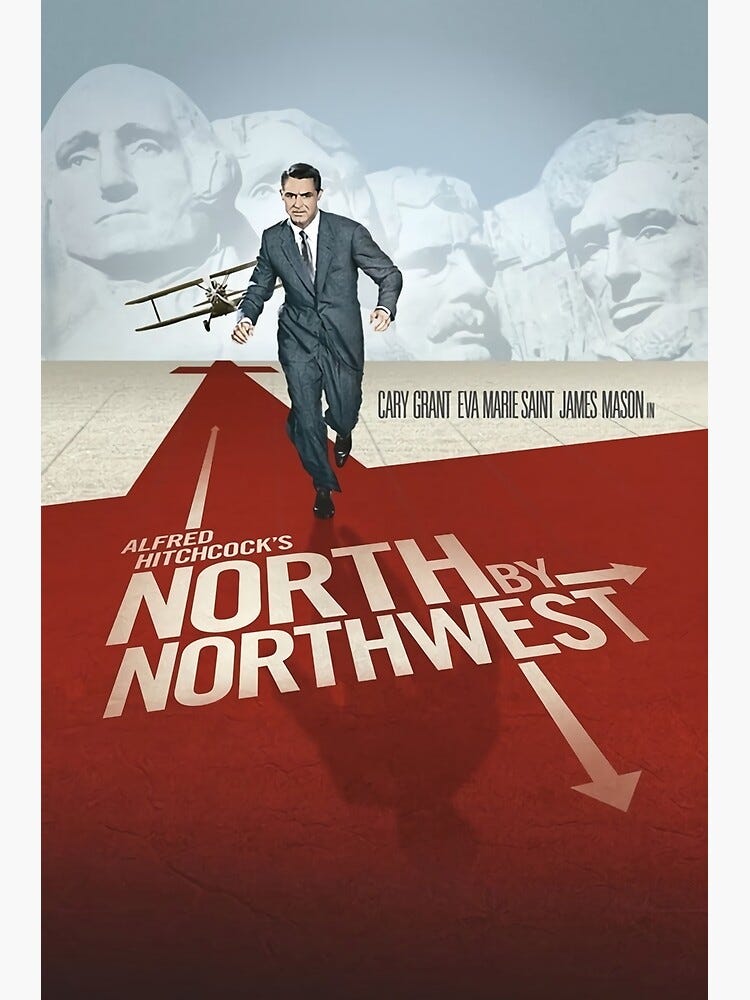

Directed by Alfred Hitchcock

United States, 1959

Arriving in 1959, sandwiched between Vertigo and Psycho, Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest is all too easily dismissed as a cinematic amuse-bouche. In the UK, it’s one of those films seemingly always playing in the background on television over a Bank Holiday weekend. But if you ever wanted to show someone who had never stepped foot inside a cinema what film really is, North by Northwest would be an ideal choice.

Hitchcock, in collaboration with screenwriter Ernest Lehman, presents us with a slice of late 1950s Americana – bright, vivid and captivating. This is an America where you can dictate a memo while riding in a cab down Madison Avenue, where the martinis flow freely at The Plaza Hotel. Traveling from New York to Chicago aboard the sleek yet spacious 20th Century Limited—a train, in case you were wondering—the elegant dining car is abuzz with passengers sipping Manhattans, Gibsons, and, naturally, the driest of martinis.

Hitchcock is offering us a dream: the Cold War here feels more like a thrilling game than a looming threat. This is the New York advertising world before the arrival of Don Draper and the Mad Men of the 1960s. Before the misogyny, racism, and chain-smoking that inevitably led to lung cancer. Somewhat ironic then that this vision of America was crafted by a greengrocer’s son from Leytonstone in East London, and headlined by Cary Grant, a Bristol-born former vaudeville acrobat. An acrobat who wore his acting talent as lightly as his bronze perma-tan. An entertainment then, but this is Alfred Hitchcock after all, and while North by Northwest may not have the intense morbid obsessions or near-psychosis of some of his other work, there is still a pervasive atmosphere of paranoia.

Grant plays Roger O Thornhill – the ‘O’ stands for nothing – a Madison Avenue adman. Drinking in a hotel bar he recalls that he needs to send a telegram to his mother, Clara. In a classic Hitchcock moment, his simple hand gesture leads to him being mistaken for a mysterious spy named George Kaplan. Before you know it, Thornhill is being whisked away to a mansion in upstate New York where he is interrogated by criminal mastermind, Philip Vandamm (James Mason). Unconvinced by his denials, Vandamm’s henchmen fill Thornhill up with bourbon and send him on his intoxicated way in a stolen car, expecting that he’ll fly off a clifftop. But Thornhill escapes, beginning a frantic chase that takes him across the country.

Accused of murder after being photographed with a knife in the back of a dead man at the UN General Assembly, before you know it he’s hooking up with Eva Marie Saint in her train couchette, dodging a crop-duster in that iconic cornfield, making outrageous bids at an auction house just to get arrested, and finally, scaling the presidential faces of Mount Rushmore.

All in search of answers about a man who, as it turns out, doesn’t even exist. There is also something about some microfilm hidden in a statue, but that’s a mere distraction. In North by Northwest, it’s the chase rather than the destination that is the point.

It’s a film that presages both James Bond – Dr No would be released two years later – and Mission Impossible, two franchises that try but fail to compete with Hitchcock’s visual style. Starting with the clean, geometric lines of Saul Bass’s opening credits, who else would have come up with the astonishing overhead shot of the ant-like Thornhill fleeing the United Nations building?

Although it is definitively a film of the 1950s, there is a modernism about the style that bleeds into the future. Vandamm’s Frank Lloyd Wright-inspired house is just the spot where you might expect Thornhill to bump into Lady Penelope of Thunderbirds, accompanied by Parker of course.

Apparently, somebody asked once asked Hitchcock, the master of suspense, why he never made a comedy. But of course North by Northwest is only masquerading as a suspense thriller. It really is a quintessential screwball comedy – in one chase sequence Thornhill darts through a hospital room somewhere, as a patient jumps up from her bed and says, “Don’t go…”

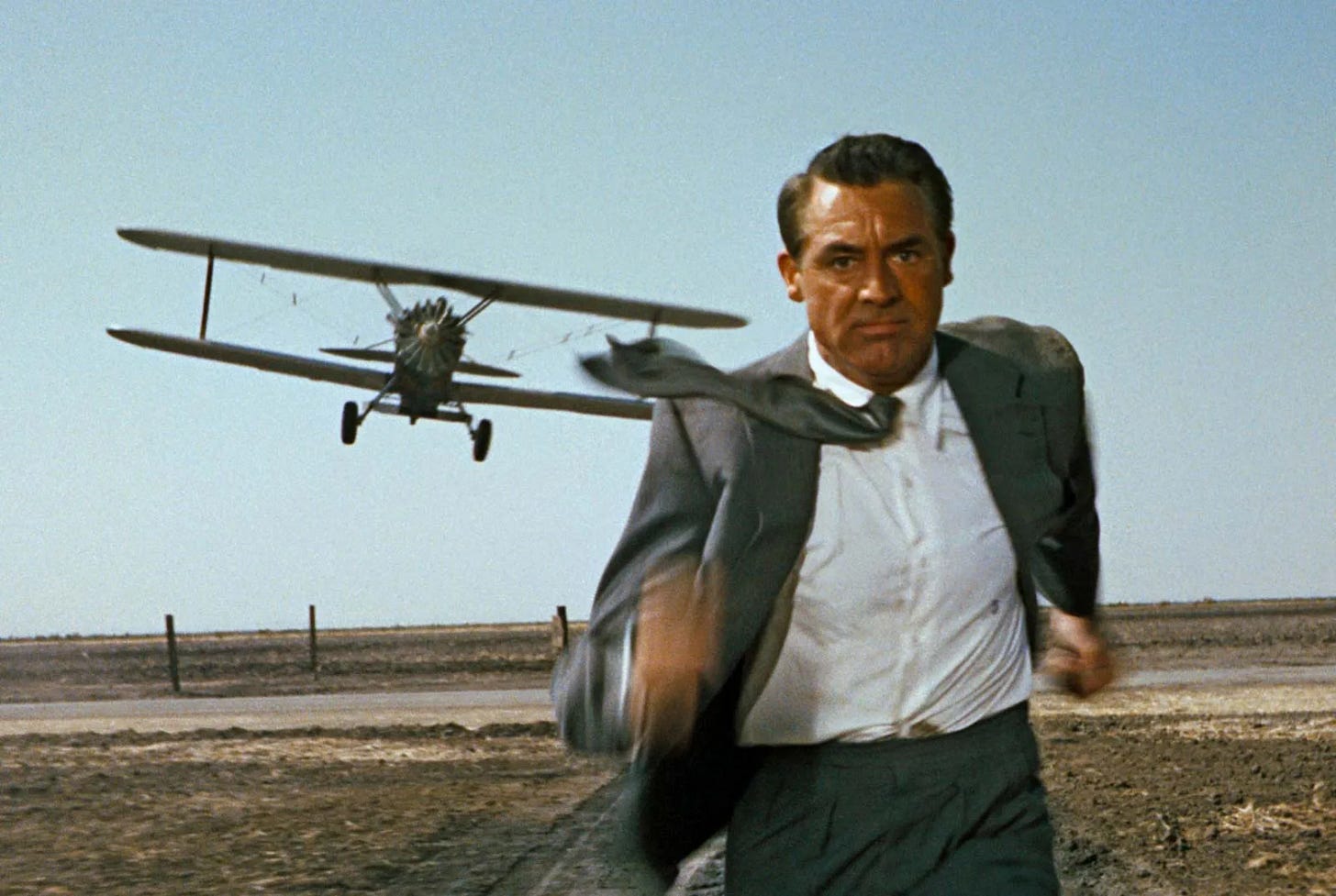

There is just one moment where the high-spiritedness vanishes. Yes, it’s that cornfield scene that forms the centrepiece of the film. Bernard Herrmann’s exhilarating, cascading score disappears just as you are expecting it to drive the momentum forward. After a story that has been busy with people, sound, and colour, Thornhill gets off a bus in the middle of nowhere – still wearing his immaculate suit, and a perfectly knotted tie. Hitchcock highlights his vulnerability by framing him against the vast, empty landscape. When a black car speeds by it briefly exudes menace, and then the crop-duster appears, famously dusting a field with no crops. It is one of cinema’s most memorable moments.

If you have a crop-duster, you must let it dust. If you have a man in an auction room, he must bid – Alfred Hitchcock

Compare that to the final showdown on Mount Rushmore in South Dakota, with the solemn faces of Lincoln, Jefferson, Washington, and Roosevelt, carved into the mountainside. A monument that is awesome and yet at the same time somehow ridiculous. And let’s face it, by this point the suspense has drained away: you know that the bad guys are done for and that Cary Grant will get his girl. And just to, erm, ram the point home, Hitchcock closes with the most brazen of sexual innuendos – the 20th Century Limited train roars into a tunnel.

The film, of course, belongs to Cary Grant but the supporting cast impress too: Eva Marie Saint, James Mason, Leo G Carroll, Martin Landau, and of course Jessie Royce Landis as Clara, Thornhill’s mother. What is it about Hitchcock and his mothers? They all seem to have a powerful and constricting hold over their sons. Even here, as comic relief, Clara is subtly controlling and any Freudian will tell you that it’s not really Vandamm that Thornhill is running away from, but the emasculating clutches of his mother – castration anxiety at its height. Of course, in Hitchcock’s next film the mother is a long dead corpse.

A boy’s best friend is his mother - Norman Bates

Arrested for drink-driving, Thornhill has to call Clara to bail him out, which does give us one of the film’s best lines:

No, mother, I have not been drinking. No, no. These two men, they poured a whole bottle of bourbon into me… No, they didn’t give me a chaser.

Reids’ Results (out of 100)

C - 74

T - 74

N - 80

S - 79

Thank you for reading Reids on Film. If you enjoyed our review please share with a friend and do leave a comment.

Coming next… Endgame(2000)

Great article about on of my favourite Hitchcock films. It’s been a LONG time since I last watched it, but it’s moving to the top of the list. And possibly ‘The Trouble With Harry’ and ‘The Man Who Knew Too Much’, come to think of it!