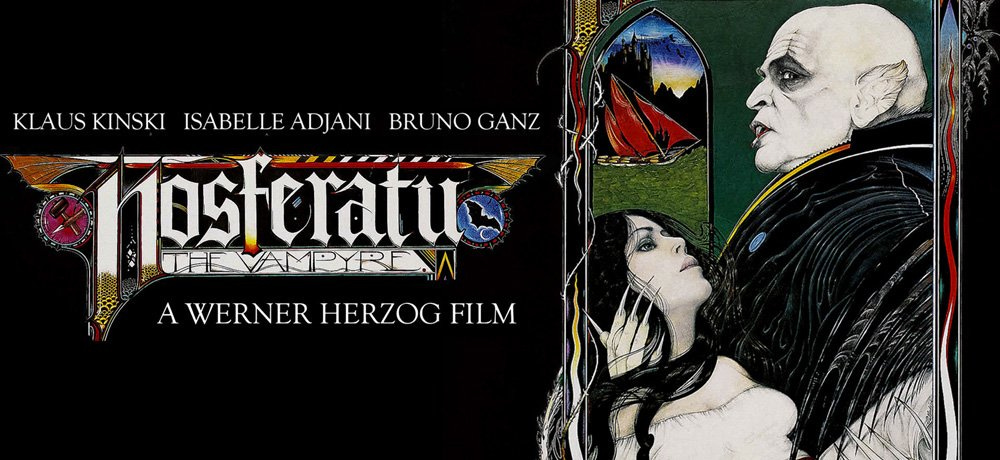

Directed by Werner Herzog

West Germany, 1979

Time passes in blindness, rivers flow without knowing their course… Only death is cruelly sure - Count Dracula

This week, we have a retelling of Bram Stoker’s Dracula with Werner Herzog’s 1979 film, Nosferatu the Vampyre. This is the third Herzog film reviewed by ReidsonFilm, and for those familiar with his distinctive style, it will come as no surprise that this is a version of Dracula unlike any you will have seen before. In fact, what we have is reimagining of the original Nosferatu, the 1922 silent film by F.W. Murnau.

Then, Count Dracula was named Nosferatu as he was still under copyright but Herzog had no such limitation, and although he kept the title, he eschewed many of the familiar tropes we have come to expect with gothic vampire tales. The titular character is played by Klaus Kinski, in his usual inimitable mode. A pathetic, even sympathetic vampire, the true horror is the torment of his eternal life.

Nosferatu begins with our protagonist Jonathan Harker (Bruno Ganz), persuaded by supposed estate agent, R.M. Renfield (Roland Topor), to make the four week journey from his hometown of Wismar, Germany, to Transylvania where he is to finalise a local property sale with Count Dracula. This job promises a large commission that Harker believes will fund a new house for his deserving wife, Lucy - an otherworldly Isabelle Adjani. Renfield cannot withhold an unnerving cackle as he remarks that the task will demand, ‘a lot of sweat’ and ‘perhaps also a bit of blood.’ Ignoring this forewarning as well as the apprehension of his wife, Harker embarks, embodying the rational scepticism of the modern man.

On his way to the castle, Harker spends a night at a remote village inn. Casually mentioning his destination, the villagers turn to him in stunned silence before warning him of the evil spirits at Dracula’s castle. They all share a great terror of Dracula, a fear rooted in folklore. Harker has no time for this ‘superstition’ and continues on his journey with one slight problem: no one is willing to direct him to the castle or even lend a horse to get him there.

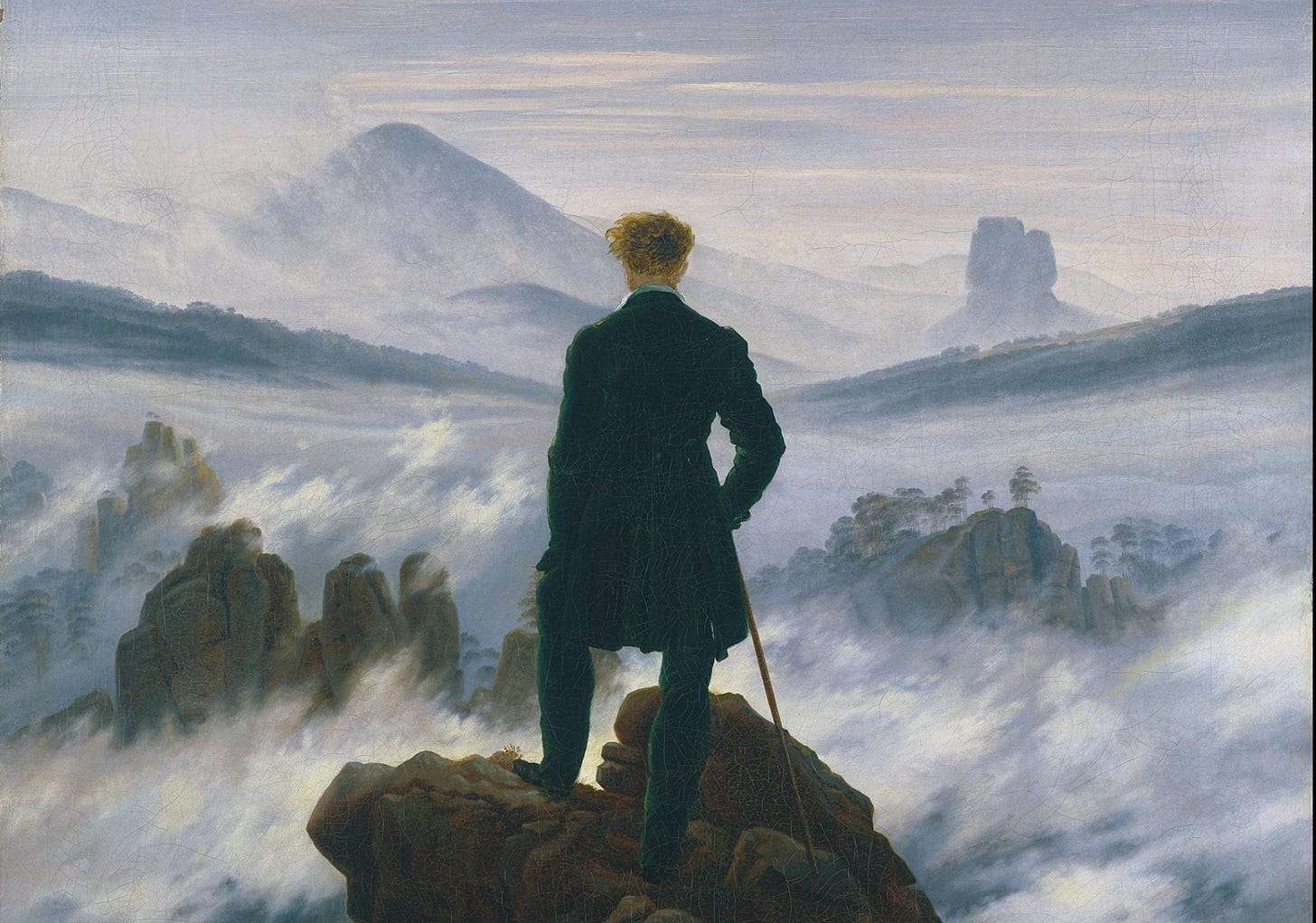

So, he continues on foot, up through the fog-shrouded mountains, past waterfalls and along narrow trails overlooking chasms. Herzog invokes the sublime, using the majestic yet eerie landscapes to heighten the sense of foreboding. These beautiful yet perilous environments are reminiscent of Herzog and Kinski’s earlier work, Aguirre, the Wrath of God, and serve to highlight the powerlessness of humanity in the face of the indifferent forces of nature. And what better score than the ominous tones of Wagner’s Overture to Das Rheingold to accompany Harker’s ascent to the castle stairs? However, when the gates creak open and the music fades, we are not met with the tall and elegant Dracula that one might expect. Instead, Kinski’s Dracula lingers in the shadows: frail, ghastly, with pallid white skin and dark sunken eyes.

His abode is stark. There are no servants in sight. The labyrinthine castle is defined by white, featureless walls; a deliberate departure from the expected grandiose gothic furnishings. This minimalist setting amplifies the unsettling atmosphere, stripping away any semblance of opulence and instead highlighting the desolation and emptiness that surrounds the Count. The corridors are silent, except for echoing distant moans.

Like you don’t get all the tired tropes of gargoyles, creaky gates, pointed spires, thunder and lightning spurs - C

Kinski’s Dracula appears vulnerable, and yet when Harker cuts himself on a comically blunt knife, the Count cannot suppress his thirst for blood and still manages to evoke fear. Not as a traditional villain, but more as a tormented creature. Tormented by that curse of eternal life, Dracula’s immortality isolates him from mortals, an isolation he is desperate to break.

It is this longing that propels the rest of the film, as Dracula becomes obsessed with a locket containing a picture of Harker's wife, Lucy, and races off to find her, leaving behind a severely anaemic, and newly possessed Jonathan Harker. As the narrative escalates to its climax, Herzog presents us with a series of trademark visual flourishes: Dracula sailing downriver on a raft laden with black coffins, the town of Wismar overrun with rats as a group of its citizens act out their very own Last Supper.

As well as the overarching theme of mortality, Nosferatu sets off a clash between faith and science, as the town’s doctors ridicule Lucy’s intuitive understanding of why Wismar’s life expectancy takes a drastic downturn:

We live in a most enlightened era. Superstitions such as you mention have been refuted by science.

As Dr Van Helsing finally hammers a stake through Dracula’s heart, it is clear where Herzog’s sympathies lie. But it is the combination of poignant imagery and striking tableaux that will linger in the mind. Herzog masterfully weaves together haunting visuals and a deep sense of melancholy, leaving us both unsettled and captivated. In rejecting cliche, this reinterpretation of the classic vampire tale with a commanding lead performance manages to craft a highly entertaining, yet profound, parable of the human condition.

Werner Herzog: Cinema’s great Romantic - S

Reids’ Results (out of 100)

C - 73

T - 80

N - 78

S - 88

Thank you for reading Reids on Film. If you enjoyed our review please share with a friend and do leave a comment.

Coming next… Threads(1984)