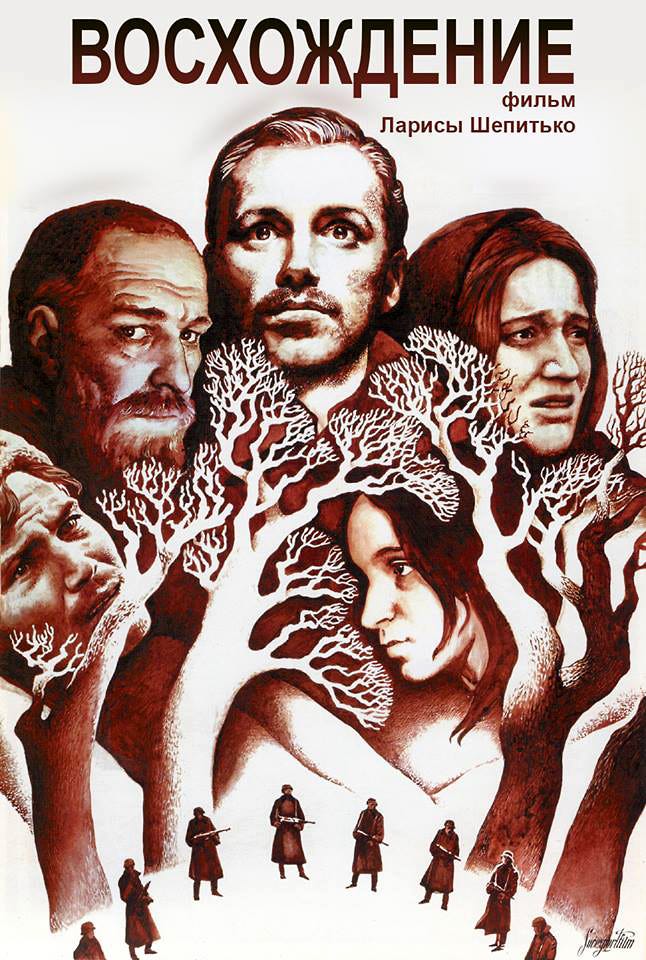

Directed by Larisa Shepitko

Soviet Union, 1977

The actors had to feel the winter all the way down to their very cells

Last week, in our review of Werner Herzog’s film Aguirre, the Wrath of God, we highlighted the director’s use of challenging locations and adverse conditions to draw the viewer into a world that is both incredibly real, yet also sublime. Larisa Shepitko in her 1977 film The Ascent takes that approach to the extreme. Shot almost entirely outside, in a Russian winter with the temperatures at 40 below freezing (the only temperature at which Celsius and Fahrenheit match), Shepitko had snow blown directly into the faces of the lead actors before each scene. The effect is to move beyond the real into an ethereal, otherworldly space that mirrors the dramatic shift in the form of the film itself, from cinematic realism to a parable of sacral myth.

The film’s opening is bleak, brutal, yet also beautiful. The screen is a white-out. A snow-laden landscape with gunfire crackling in the distance. Abruptly, dark figures emerge in a field. This is Belarus in the winter of 1942, and they are Soviet partisans and villagers in hiding. They manage to find cover from Nazi soldiers in pursuit, but they are left frostbitten, starving, and out of ammunition. Two men, an experienced soldier, Rybak (Vladimir Gostyukhin), and a pale, gaunt, teacher turned sniper, Sotnikov (Boris Plotnikov), are sent to a nearby village to find food. So, an adventure story: men on a mission, filmed with a handheld camera - giving a sense of the urgent and the immediate.

The men find food and lose it. After getting caught up in a gunfight with Germans on patrol, during which Sotnikov gets shot in the leg, they are finally discovered hiding in the barn of a sympathetic farmer, Demchika (Lyudmila Polyakova), mother of three young children. The pair are taken off to the soldiers’ camp, Demchika as well, leaving her children behind, and alone.

It is at this point that Shepitko skews away from an action-heavy drama, a film depicting the horrors of war, to an existential meditation. A film asking the question: “What is it to live?” The tension is just as acute, but it now takes a different form. The men are interrogated by the local police chief, a Nazi collaborator and Sotnikov is tortured when he refuses to answer any questions. A star is branded on his bare chest with a hot iron. In a surprising contrast, Rybak is immediately compliant, giving up information readily and when offered the choice to be hanged with Sotnikov or to collaborate, he opts to join the police and work for the Nazis. These scenes form the centrepiece of the film. Rybak, previously the strong man, has become weak and Sotnikov, the weak one, become strong. Portnov (Anatoliy Solonitsyn), the interrogator is confused by Sotnikov’s defiance. The expression on his face shows it. Rybak is who he identifies with, and so projects all of his fear, and self-loathing onto him.

From here, the religious symbolism and iconography becomes more explicit: a crown of thorns, an empty tomb. We witness ‘the ascent’ both literally and spiritually as the condemned man climbs a hill to his execution – an obvious allegory of The Crucifixion. Sotnikov’s face is framed in bright light, giving him a divine aura to complete his beatification. Alongside him, Demchika, a village elder, and a young Jewish girl discovered in hiding are also to be hanged. Rybak is the repentant disciple. A passing woman even hisses at him, “Judas”. One of The Ascent’s final shots is of Rybak looking out over the landscape, imagining the freedom that he can never attain. Skewed telegraph posts run through the valley, looking like the crosses that lined the Appian Way.

The Ascent is by no means a subtle film, but it has a power that will leave these images inscribed on your memory. The cinematography impresses with deep blacks set against burnt-out whites. Then, intense, close-up shots of the actors’ faces looking directly into the camera lens. The performances are impressive, particularly from the two leads, who were relative unknowns. There is one gruelling scene earlier in the film where we see Rybak dragging the wounded Sotnikov through the snow, the two men locked in an embrace, not knowing where they will end up… or indeed where they will end.

Trudging through waist-deep snow, engulfed by a white abyss. Man against an uncaring nature. We have been here before with Aguirre and of course, Dersu Uzala - N

As a filmmaker in the Soviet Union Larisa Shepitko had to fight against the constraints of censorship but she was uncompromising in her attitude to her art: “You have to approach each film as if it were your last.” Tragically, The Ascent was her last completed film. She was killed in a car accident in 1979 while scouting locations for her next film.

“No photograph, or portfolio of photographs, can unfold, go further, and further still, as does The Ascent … the most affecting film about the horror of war I know.” - Susan Sontag

Reids’ Results (out of 100)

C - 72

T - 77

N - 75

S - 78

Thank you for reading Reids on Film. If you enjoyed our review please share with a friend and do leave a comment.

Coming next… Synecdoche, New York(2008)

Mind blowing