Directed by Miklós Jancsó

Hungary, 1966

The year is 1869. A landscape in black and white – we are in Hungary, on the sun-scorched Great Plains. We see an army approaching. Soldiers on horseback are rounding up prisoners. The opening dialogue tells us that 20 years after the failed 1848 revolution the Hapsburg empire is triumphant.

Whole villages are detained en masse as the Austrians attempt to root out the remnants of a rebel army. The partisans are marched off to a stockade where the interrogations begin. It’s a game of cat and mouse: the prisoners are isolated, threatened, offered deals for information. The guards are trying to find the legendary Sándor Rózsa, former highwayman turned Hungarian folk hero. But it’s not clear that he is even in the camp.

The camera focuses on one prisoner who looks a heroic type. Perhaps here we have the film’s protagonist. He is led away, told that he is released but as he walks free heading for the plain a guard shoots him dead. As far as plot goes that is pretty much it…

An understanding of Hungarian culture may or may not be helpful here. As well as being a physical space, the stockade captures a state of being. Another prisoner is identified as a murderer by an old woman and he is offered the chance to save himself by identifying the ringleaders:

Austrian prison officer: Do you accept this condition?

Hungarian detainee: Well sir, I must

Once back in the fold it is confusing why the other prisoners take so long to identify him as the snitch – his repeated bartering and begging with the guards is hardly discrete.

Would you trust this man?

The director, Miklós Jancsó, interweaves these prison scenes with long takes of geometrical patterns of soldiers, horses and prisoners moving around the plain in formation. Like an elaborate ballet there is something unsettling about these ritual parades, although there is something of the artistry we saw in the choreographed parade grounds of Beau travail. The whole exercise however seems to be without purpose. The question here is whether I am referring to the narrative or the film itself?

Jancsó is clearly making an allegorical statement. The Round-Up is a historical study but also points to the Hungarian uprising in Budapest of 1956, just 10 years before its release. For a few days in that year, Hungarians rose up and took back the streets in the capital before the tanks of the Soviet Union rolled in and violently crushed the nascent rebellion.

Budapest, 1956

Jancsó started his career in film as a documentary-maker and later remarked that making newsreels under Stalin was an excellent training ground for making fiction later on. Working under the Communist authorities meant that Jancsó had to negotiate his way past the censors with allegory and symbolism, but it did have its upsides. He had ready access to hundreds of extras to populate his films as is evident here.

So the Round-Up is a testament to how a people can be cowed, intimidated and broken down, but it is not an easy watch. There is an austere formalism to the film that alienated some of ReidsonFilm. There have been countless films exploring the themes of power and totalitarianism. The absurdism of The Round-Up is shared by Orson Welles’ 1962 version of Kafka’s The Trial. But Welles’ film has a Beckettian humour and yes, warmth, which is lacking here. Jancsó is closer in spirit to the novel Darkness at Noon, the bleak story of an Old Bolshevik who is arrested and imprisoned for treason by the government that he established – written by the Hungarian-born writer Arthur Koestler. In undermining any notion of character or psychology, Jancsó has produced a work that we struggled to engage with: we are observers of a spectacle sealed within a hermetic space.

A lot of people just stood around pointing fingers at each other. Was like a scene from the principal's office at school - N

There was this sense of waiting, the interstitial space. The confined body vs the confined space: Foucault and the Carceral State - C

So formally challenging cinema but what a visually striking film. Jancsó and his cinematographer, Tamás Somló, capture a sublime, but so oppressive, light on the grassy plains that also reflects harshly on the isolated, angular whitewashed buildings. The landscape shots occupy the whole screen, recalling Sergio Leone’s great Western Once Upon a Time in the West. Paradoxically though, the freedom offered by the open terrain here is illusory. It proves to be as much of a prison as the stockade. The director repeatedly uses sweeping crane-mounted tracking shots to follow the movement of bands of peasants through the grass or groups of horseman thundering past the camera. We highlighted Akira Kurosawa’s mastery of movement in our recent take on Slow Cinema and the staging of bodies and their motion in The Round-Up is worthy of comparison with Seven Samurai, or even Ran.

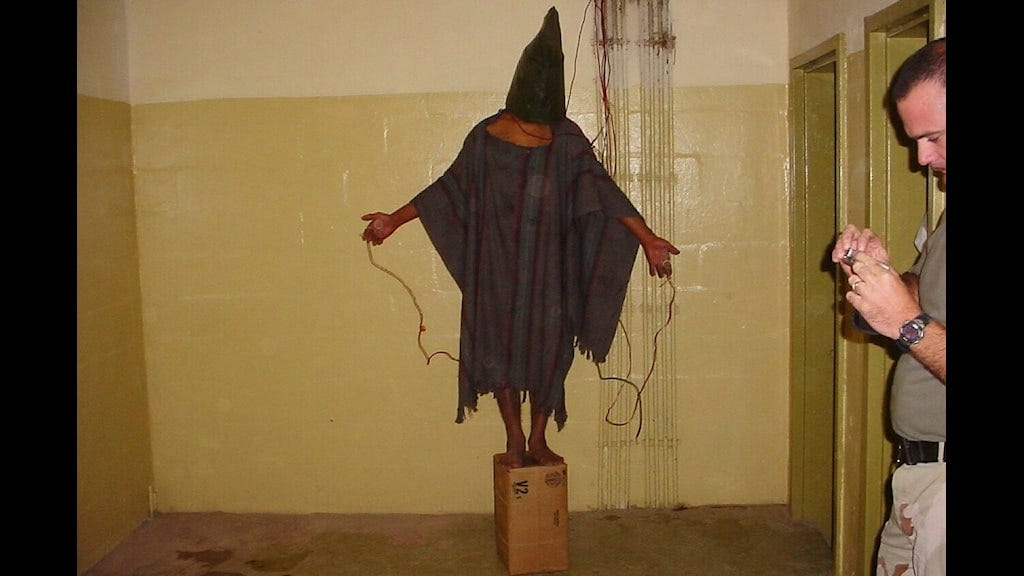

Jancsó’s ascetic approach to film here does not exclude some scenes that will stay with you. The violence on screen is largely psychological with the exception of one rather voyeuristic scene, where a naked woman is brutally whipped to death by the soldiers. That precipitates a number of the prisoners to throw themselves from the stockade roof to their deaths. And then we have that haunting image of the hooded prisoners being paraded in a circle – art can presage reality:

Detainee of the US Army at Abu Ghraib 2003

The Round-Up is a pessimistic film, but nonetheless realistic. The closing scenes offer a glimmer of hope, but it really should come as no surprise when Jancsó snuffs it out.

A film to admire rather than enjoy. It felt like film as theory rather than experience. A bit like those paintings by Mondrian with a few lines and coloured squares... - S

Reids’ Results (out of 100)

C - 64

T - 64

N - 55

S - 71

Thank you for reading Reids on Film. If you enjoyed it please share with a friend and do leave a comment.

Coming next … Remainder (2015)