Directed by Stanley Kubrick

United States, 1980

A boy, five-years-old, pedals his Big Wheel tricycle along a hotel corridor. The sound alternates between explosive noise as the wheels track the hardwood floor and silence on carpet. The boy turns a sharp corner. Two creepy girls dressed in blue appear, holding hands, twins – yet not twins.

Hello Danny, come and play with us.

Danny stops still, staring. Momentarily, a bloodied vision of their brutal murder flashes across the screen. An axe lies in the foreground, blood spattered on the carpet and walls. Danny clasps his hands to his face, then peaks through his fingers. Danny is us, the audience, watching. Next moment, the girls and the blood are gone. Danny speaks to his imaginary friend, Tony:

Tony, I’m scared.

Tony responds:

Remember what Mr Halloran said. It’s just like pictures in a book. It isn’t real.

This is one of the most horrifying scenes from The Shining, Stanley Kubrick’s great horror film. But not really a horror film if you think about it – it’s unanchored from any genre at all. The Shining is not really a film of monsters, or gore. There aren’t so many jump scares and most of it is shot in daylight. It is though a film that over time builds an atmosphere of dread, more successfully than any other film I can think of.

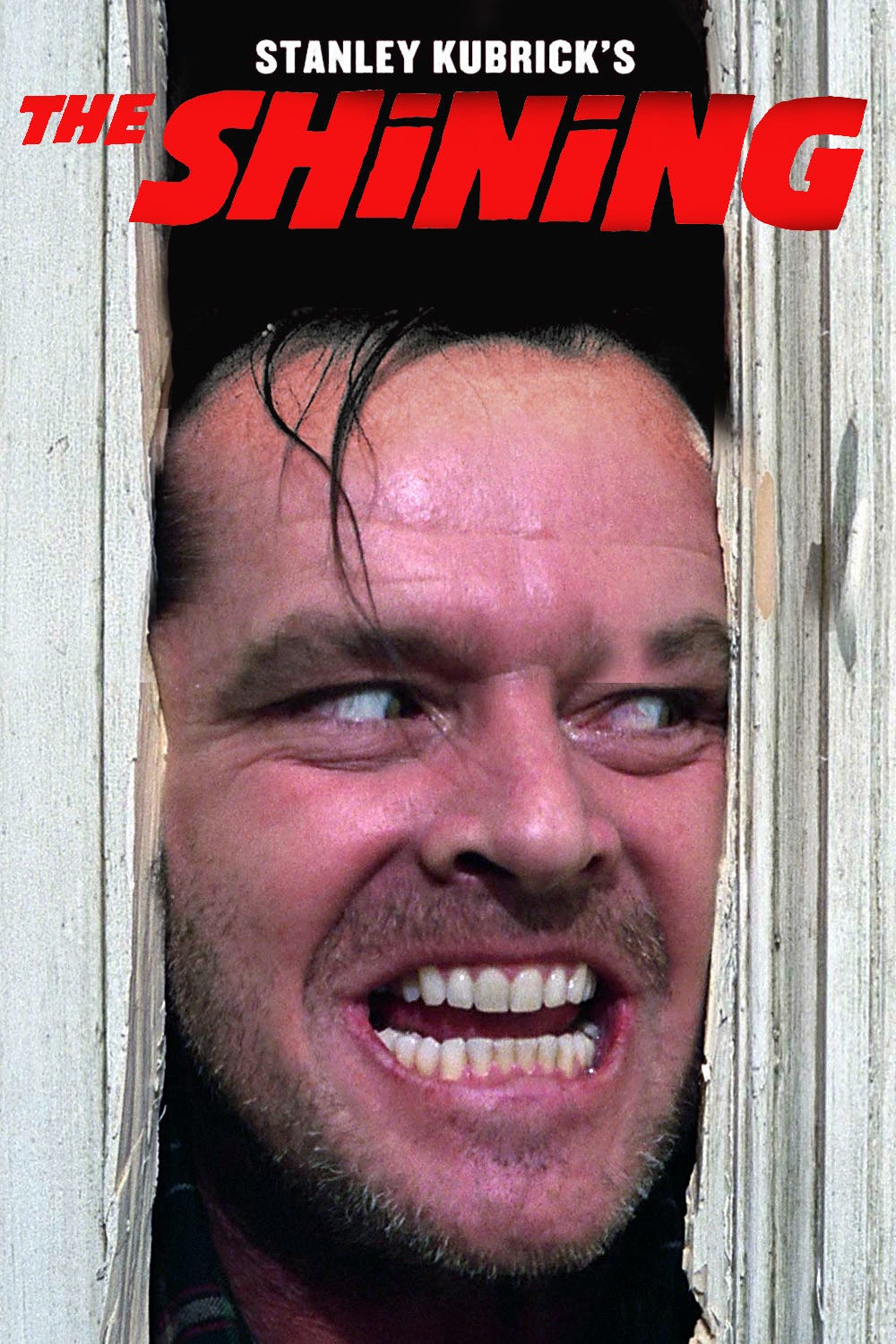

Most are familiar with the plot of The Shining even if they haven’t seen it. Jack Nicholson’s deranged expression as he peers through a hole in the door, and improvises that infamous line, ‘Here’s Johnny!!’, has been voted the Scariest Movie Moment of all time.

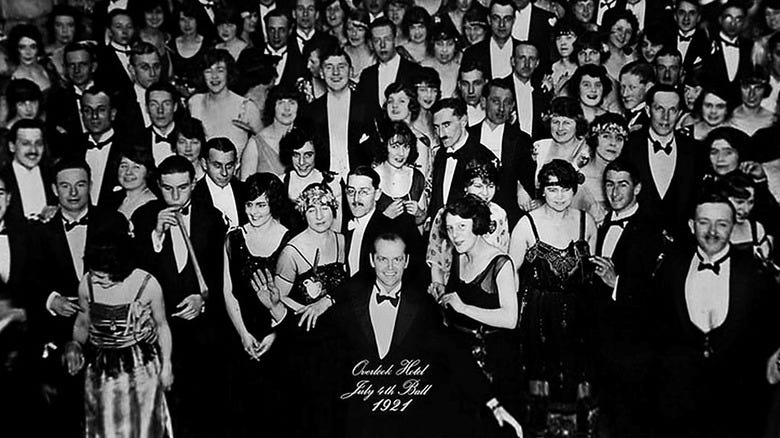

The film has developed an enigmatic reputation since it’s release in 1980, reinforced by Kubrick’s renowned fastidious attention to detail. Countless attempts have been made to peel back the layers in search of hidden meanings, to the extent that a documentary, Room 237, was made to test out a range of fan theories. Including one that The Shining was an apologia for Kubrick’s role in faking the Moon landings.

The story is a simple one, adapted from a Stephen King novel. A story of family life: Danny Torrance, a boy with a mysterious telepathic ability known as the Shining has an imaginary friend, Tony, who warns him of sinister forces at play. His father, Jack, a struggling writer is hired as winter caretaker of the Overlook, an elegant hotel isolated high in the Rocky Mountains. Jack, his wife Wendy (Shelley Duvall), and Danny are sealed off from the outside world for the winter by snowfall. But the Overlook has a dark history, and as strange things begin to happen, madness ensues.

For a fresh look at The Shining ReidsonFilm trooped along to see the film at London’s BFI IMAX, on a screen the height of five double-decker buses. From the astonishing opening scene, as Jack wends his way in a yellow Volkswagen Beetle through the Colorado mountains, it was clear that we were in for something new. The camera sweeps over the vastness of the vertiginous landscape, mirrored against a tranquil lake, and the eerie, electronic adaptation of Dies Irae (composed by Wendy Carlo and Rachel Elkind) is intensified by the IMAX’s enhanced sound system. Dies Irae: Day of Wrath… indeed.

Paradoxically, the enormity of the cinema screen only served to heighten the oppressive claustrophobia of the Overlook Hotel, with the detailed patterning of the carpets and the chilling symmetry of the hallways. We were now in the most liminal of spaces.

And within that space Kubrick disrupts both the continuity and geography to unsettle the audience. We have intertitles: ‘A month later’, ‘Tuesday’, ‘Saturday’, ‘Wednesday’, then ‘4pm’ that telescope time as Jack’s mental state unravels. The Overlook itself has an impossible geography. The garden maze doesn’t exist in the opening shot of the hotel, and just try and map out the interior by following Danny as he cycles around.

However, it’s not just the visual immersion that has an impact. Stuck in the hotel with the Torrance family for a couple of hours, the gender politics soon erupt and the Gothic trappings of the film are much less disturbing than the family violence and emotional abuse. Jack is supposed to be a writer, but has he really ever published anything? Waking at 11am to a breakfast provided by Wendy, he refuses to accept responsibility for anything. His life has been a failure, and of course it’s all his wife’s fault, or as he refers to her, ‘the old sperm bank upstairs’. Meanwhile, mocking Jack’s narcissistic ego inflation, it is Wendy who is running the boiler, and setting the hotel’s CB radio - their only connection with the authorities. Who is the real caretaker here?

A sense of unease is there from the start when, after an apparent seizure, Danny is examined by a paediatrician. The look on Wendy’s face as she lies about Jack’s ‘momentary loss of muscular coordination’ and Danny’s dislocated shoulder cannot hide her deep disquiet, and fear. Jack and Wendy: names familiar from fairy tales, and fairy tales loom large in The Shining. Jack as the Big Bad Wolf, Wendy wanting to leave a trail of breadcrumbs, and putting on her Red Riding Hood jacket as she enters the labyrinth. Of course, fairy tales are another means of revealing hidden traumas: the Freudian ‘return of the repressed’.

The paranormal events at the Overlook could be considered the result of dissociation or delusion, but when Jack is released from the cold storage room by Mr Grady, the long dead former caretaker, what are we to make of this genuine supernatural intrusion into a physical space?

Grady: Your wife is much more powerful than we thought. It seems we underestimated her. She needs to be taught a lesson and punished in the most severe way possible.

The lesson that Wendy learns, of course, turns out to be very different.

Stanley Kubrick’s reputation as a director is one of perfectionism and control-freakery. He was the filmmaker that demanded repeated takes from his actors, to the point of cruelty. Yet in The Shining, Kubrick did allow the actors to improvise with the script, and he made use, not only of hand-held cameras, but the spontaneity of the newly-invented Steadicam. The fluidity of the camera movement as it tracks Danny cycling around the hotel corridors or running through the snow into the maze is what makes those scenes indelible. Rather than having the film meticulously storyboarded, scenes and the script changed on a daily basis.

It is clear however that The Shining would not work without the eccentric performances of the two leads. Jack Nicholson’s famously lupine performance as the abusive and ultimately ineffectual caretaker is over the edge and over the top, but over the top is what the director needed.

Kubrick: Real is good… interesting is better.

Of the two though, Shelley Duvall arguably has the more complex and certainly unsettling role. From the start she has a china doll fragility, particularly evident in her defensiveness about her husband:

I don’t believe he meant to hurt him.

Her round eyes widen, as she trembles and her cigarette ash lengthens. And when Jack does finally break, those eyes show the shock, not of someone being chased by an axe-wielding murderer, but the emotionally draining recognition of a woman who can see her partner’s violence boiling over once again.

Danny Lloyd is preternaturally controlled and nuanced as their son and then we have the supporting players: Scatman Crothers as Dick Hallorann, the head chef of the Overlook. The father that Danny needs rather than the one he has, prepared to trek through the snowbound landscape to affect a rescue. And the spectral Joe Turkel as Lloyd the bartender, whose role is made explicit when Jack takes a seat at the bar:

I'd give my goddamn soul for just a glass of beer.

A cheap trade indeed. But let us not forget the hotel itself. The Overlook is the character that reveals what it wants you to see, when it wants you to see it: Stanley Kubrick’s eternal Picture House. Is The Shining his masterpiece?

It’s the best film of all time, it’s only fair it gets the best possible score - C

Reids’ Results (out of 100)

C - 99

T - 93

N - 95

S - 88

Thank you for reading Reids on Film. If you enjoyed our review please share with a friend and do leave a comment.

Orson Welles said of Kubrick: Among those whom I would call ‘younger generation’, Kubrick appears to me to be a giant.

Both of them great American film directors, but both ending their careers in exile overseas. Unlike Welles who arrived in Hollywood to a great fanfare, Kubrick started small with films on a shoestring budget. Yet, while Welles spent his final years struggling to pull money together to shoot footage, Kubrick ultimately mastered, and dominated, the studio system. If you missed our review of an early Kubrick work, you can find it here:

Coming next to ReidsonFilm… Omen(2023)

Strong disagree with it being the best of all time. It’s not even the best Kubrick. Agree that it’s good, though.

Great write up. Most of the film was shot at Elstree Studios, including the outside of the Overlook hotel -- a huge set was built on the backlot. My bedroom window looks out on the very spot where it once stood... a space that was recently occupied by the Buckingham Palace set from The Crown.