Directed by Krzysztof Zanussi

Poland, 1969

The Structure of Crystal opens with a crisply shot, black-and-white scene of two people pacing in a snow-covered field. They are waiting for someone to arrive in a car. The camera is still and the perspective places them in a single plane, as a horse-drawn sled passes them by. Order and symmetry: this seems appropriate for a film about two physicists. Polish director Krzysztof Zanussi’s feature debut is a visually captivating chamber piece about friendship, about differing views of the world, and yes, about science.

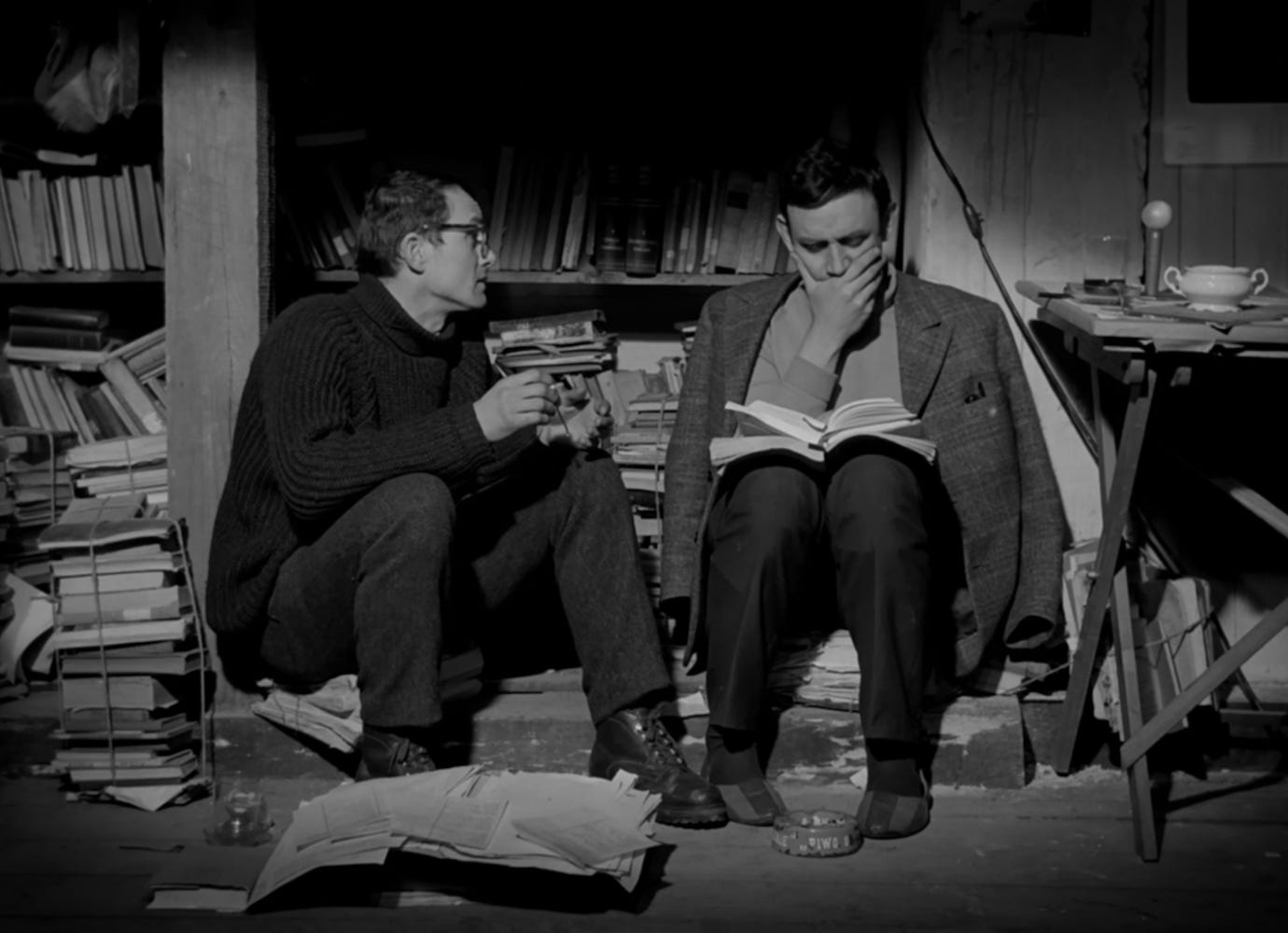

It is 1969 and Poland is living through the interminable years of the Cold War. Jan (Jan Myslowicz) and Marek (Andrzej Zarnecki) are two friends in their late 30s, and former university colleagues. Their lives have taken divergent paths. They were both high-flying academics, but Jan left his research behind to work on an isolated meteorological station. He lives with his schoolteacher wife, Anna (Barbara Wrzesinska), and her curmudgeonly father. Marek has built himself a successful academic career, studying crystallography, and is visiting Jan having just returned from a teaching post at Harvard in the United States. They haven’t seen each other for years and spend time reminiscing about their student days, but Marek is bemused and frustrated by Jan’s withdrawal into what he considers a banal existence. Midway through the film Marek compares his visit to a Chekov play:

We’re only missing a samovar. Everybody’s having tea. Silence and nothing happens.

Anne responds:

Actually there’s a lot happening in Chekhov’s plays.

And there is a lot happening in The Structure of Crystal. A quiet, meditative film, but the conflict is one of ideas and no less vital for that.

The exact reason for Jan’s move to the countryside is never made explicit, but he changed course after a climbing accident that left him hospitalised for six months. Marek’s climb up the academic ladder has clearly involved some political compromise and while Jan and Anna struggle with their bills, he is smartly dressed, owns a Volkswagen Beetle, and gets to fly abroad. There are hints that this sort of compromise may in part underlie Jan’s departure.

Marek’s competitive spirit means that the reunion involves long periods of quiet, punctuated by bouts of arm-wrestling and foot races in the snow. Whenever the opportunity arises he switches to jazz on the radio, in contrast to Jan’s classical music. Over the course of the film, he tries to antagonise Jan, exhorting him at one point to grow up, accusing him of messing around like a 12-year-old, and then paradoxically complaining that he is wasting his best years:

It makes me sick to see a man like you living like a pensioner.

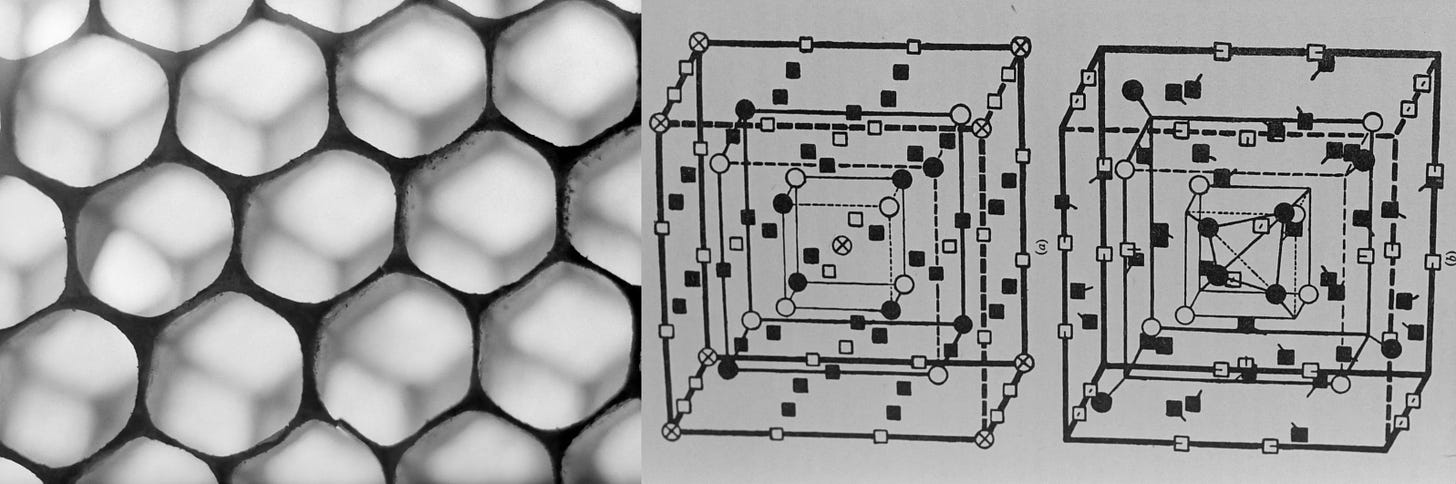

Marek, in what seems a provocative move, starts flirting with Anna, but she is having none of it. When he rather condescendingly asks his friend how he fills his days, a montage follows showing Jan and Anna, baking bread, and harvesting honey. The camera zooms in on a piece of honeycomb, mirroring a slide of Marek’s crystals.

Despite the needling, Jan is content with his lot, happy in his own skin. Marek gives a lecture to the local villagers, describing his research which involves the artificial creation of crystals. He tells the vaguely disinterested townsfolk that they will be much more beautiful than those that occur naturally. His goal is to outdo nature; Jan is happy to embrace it. The friends discuss their work: Marek is focused on a specialized problem in physics of crystal and Jan ponders the concept of infinity. They realise that they are talking at cross-purposes, but this also reveals fundamentally different ethical positions in the two men.

For the Greeks, for Aristotle and Plato, infinity was something imperfect, something worse than the finite.

This fits with Jan’s worldview, a willingness to embrace the messy, uncertainty of nature. All of this talk of physics, yet The Structure of Crystal is no dry treatise. This beguiling film seamlessly weaves science and philosophy into a delicate essay on friendship. Later, it is revealed that Marek’s visit was motivated by instructions from his boss to persuade Jan to return to the university. And yet, if Zanussi’s sympathies seem to lie wholly with Jan, he does allow Marek to argue his case:

You know, when I was twelve, that was a period of fantasy-making. I imagined I was a pilot, a chimney-sweeper, a pirate. I invented inconceivable stories in which I believed entirely. To myself, I was really all that I imagined. But I was 12 years old and you are 36, you see? I don’t know if you’re aware of the fact that you know only your own conception of yourself—which you have no chance of verifying. You can walk on the meadows thinking you're a saint, a stoic. Contemplate your crystal soul. But without a risk, without a fight, you’ll never learn the truth.

Like the films of Ingmar Bergman, The Structure of Crystal is a meditation on how one should live, but in contrast, here the usual Bergmanesque existential angst is replaced by a warm humanism. This film tells us that there are different ways to live. Two friends, and they remain good friends, do not see life through the same eye – but that is not necessary for their friendship. The Structure of Crystal closes with Marek leaving. Driving away in his car, he flips down the visor to block out the Sun. Sitting fur-clad in a field, Jan has set up his telescope. He points it toward the Sun and captures its image.

Has it ever occurred to you that “catching your breath” may be the right way to live? - Jan

Reids’ Results (out of 100)

C - 64

T - 83

N - tbc

S - 81

Thank you for reading Reids on Film. If you enjoyed our review please share with a friend, and do leave a comment.

Coming next… Heaven Knows What(2014)

Is the tbc c’d?