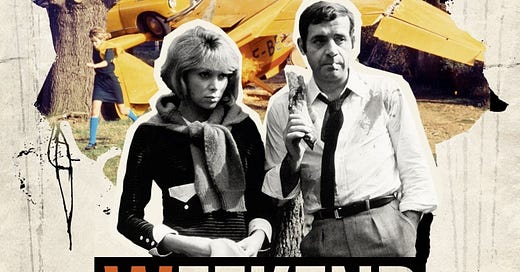

Directed by Jean-Luc Godard

France, 1967

Well there has never been any doubt that Jean-Luc Godard was a great filmmaker. His influence on the world of cinema as a critic and as a director remains significant, but Weekend… well it proved to be one of the more divisive films that ReidsonFilm has reviewed.

Like Stanley Kubrick, Godard had a stab at every film genre going, although his approach was different: he wanted to take cinema apart.

Let’s do what has not been done – Godard

Breathless rewrote the gangster film, Les Carabiniers the war film, and Alphaville science fiction. And then you have Weekend, Godard’s take on the road movie – a work which he states in the closing titles signals the end of the story: End of Story—End of cinema. Saying that, he did go on to make at least another twenty films.

Weekend does have a plot of sorts: a married couple, Corinne and Roland, set off on a weekend trip to visit Corinne’s dying father. They are hoping to get their hands on his money and end up travelling through the French countryside on a journey where they meet the weird and not so wonderful. Among them, characters from fiction and history, Marxist revolutionaries and hippie terrorists. The countryside is littered with flaming car wrecks and artfully splayed bodies, splashed with theatrical blood. And Corinne and Roland are no heroes. They are greedy, obnoxious, cheating on each other and unbeknownst to the hospital staff, they have been slowly poisoning her father when they visit. They also appear to recognise that they are characters in a film. Think The Wizard of Oz rewritten by the Marquis de Sade.

It’s a statement piece: a protest and a provocation – C

A provocative film certainly, but where ReidsonFilm parted ways was on the question of whether Weekend was a film of ambition and complexity, a film as manifesto that makes a powerful statement about the form of cinema itself, or… had Godard left behind the fizz of ideas and cinematic invention of his earlier work to give us a tedious melange of half-baked, political hokum that felt like being bashed over the head for two hours with an original copy of Das Kapital.

Where we were agreed was that Weekend was not a pleasurable watch, but was that Godard’s intention? Random cuts in the film, music cued in the wrong places, disrupting the action with intertitles: Godard repeatedly reminds us that we are watching a film, devices that he had used since Breathless but here pushed to the extreme. Having said that, in a film that is deliberately disjointed there was the occasional episode to enjoy. As the couple depart on their trip, they end up getting into a fight with a boy dressed in a ‘Red Indian’ costume, firing arrows at them. When they bump into his parents’ car, his mother comes out and grabs Roland in a neck hold. Corinne comes his rescue, and together they start spraying her designer dress with blue paint before her enraged husband appears, blasting at them with his shotgun. Godard captures something great with this sequence. It has the anarchic brilliance of the Marx Brothers rather than Karl Marx.

And then there is the celebrated single tracking shot of Corinne and Roland working their way through a traffic jam, past a series of tableaux: people playing chess in the middle of the road, tossing balls to each other from car to car, a man wrestling with the sails of his boat. They pass a lion, some monkeys, and llamas sitting in trailers. That shot lasts for eight minutes. Far too long, but it’s always watchable, despite the hellish sound of the blaring car horns. This is Godard at his inventive best, rewriting the rules of how film can be made.

I would say Godard is heralding the end of cinema… he’s declaring the form dead and showing us why - C

But these moments of baroque brilliance were lost amid the self-indulgent, and to be honest, turgid scattershot attacks on consumerism, the class struggle and cinema itself. The film was released at the end of 1967, a tumultuous point in European history: social unrest and political protest with many expecting revolution. The US was stuck in wars overseas, notably Vietnam, and Martin Luther King Jr. was soon to be assassinated. So, the apocalyptic vision of Weekend was certainly in tune with the times.

But Godard’s politics of excess came across, for some of us, as childish and pretentious. This is most stark when we are subjected to a 10-minute lecture by an Arab and an African pair of labourers on colonialism and Marxist dialectics. It ends with the two of them inciting black GIs, returning to the US with their newly learned guerrilla tactics, to wreak havoc on the white population. Here Godard is arrogant and abrasive, but also hectoring and incredibly boring. Never one to exercise restraint, as the film tumbles towards its gratefully received ending, Godard throws in plenty of rape, murder, cannibalism (an English tourist is the victim) and butchery. The carcasses pile up, both human and animal, some of which are killed on screen – just the animals, mind you.

With all of this grandstanding, a critique that could be directed at Godard is that he is bluffing after all. Underneath that nihilism – no, cynicism – he retains a genuine love of cinema and believes that it can be a vehicle for political change. As the film finishes, no one is listed in the credits, no actor, no writer, and no production team. But who else could have made Weekend?

Whatever your opinion of this film and the career of Jean-Luc Godard, he certainly left behind a staggering legacy. Watching his work from that time takes you back to a period in the history of cinema when a film could generate thought, ideas, argument, even a fight: a time when cinema actually mattered.

It's over. There was a time maybe when cinema could have improved society, but that time was missed - Godard

Reids’ Results (out of 100)

C - 68

T - 65

N - 60

S - 59

Thank you for reading Reids on Film. If you enjoyed our review please share with a friend, and let them know that we are here every Monday, nailing our theses onto the old, oaken door of the internet. And feel free to leave a comment, whether you love or loathe the review.

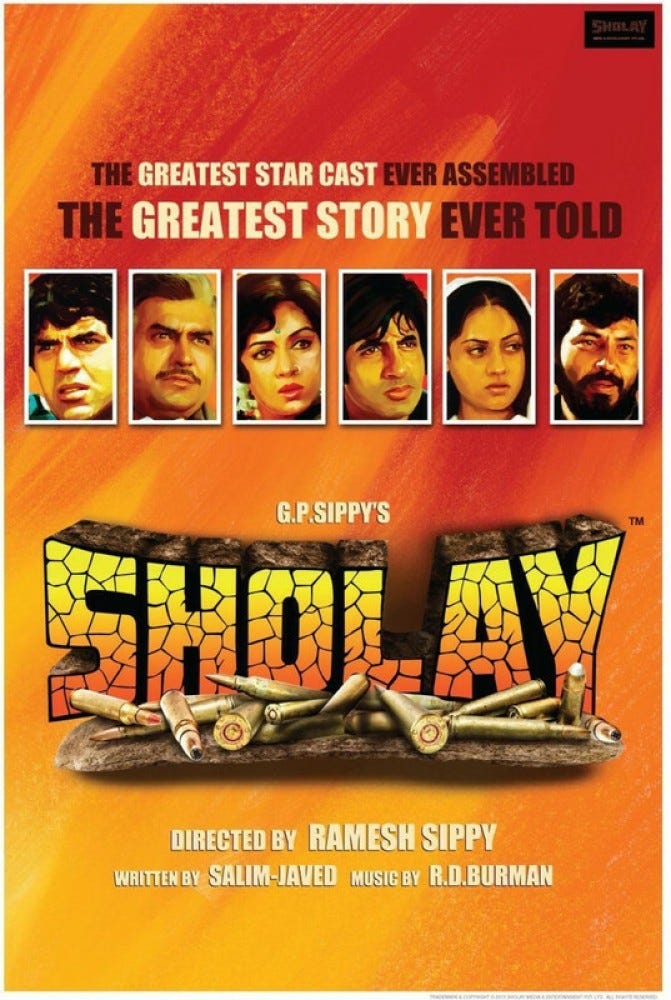

Coming next…Sholay(1975)

Love that you dove all the way to 1967 and unearthed a film "that was not a pleasurable watch" haha. made me chuckle.