Directed by Michael Haneke

France/Austria/Germany, 2003

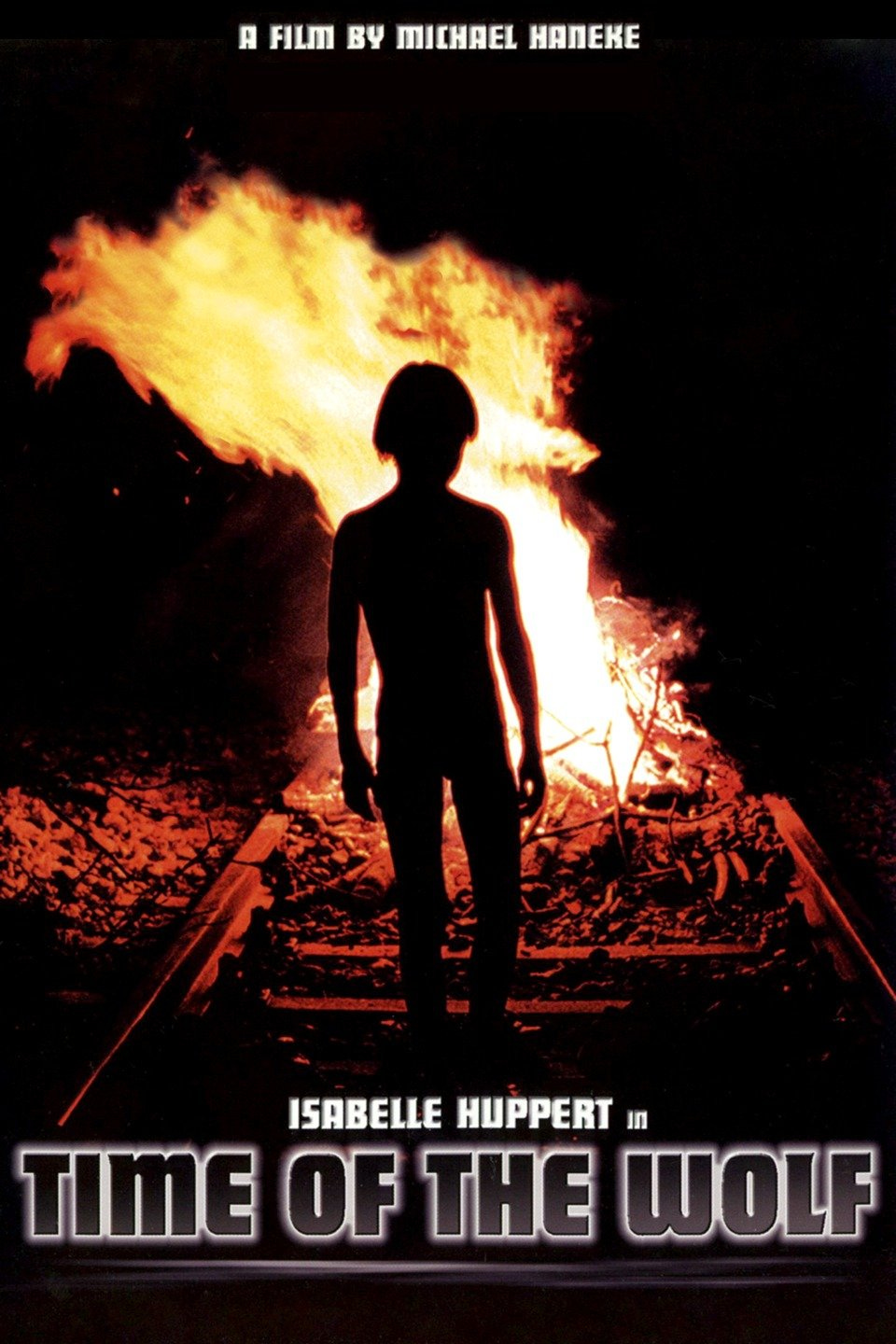

This week’s film is a disaster movie but like no disaster movie you have seen before. Released in 2003 between Michael Haneke’s critically acclaimed films The Piano Teacher and Hidden (Caché), Time of the Wolf does not seem to have had the same cultural impact which is surprising given its proximity to 9/11. But then again, that may be the explanation for the film’s muted presence. Watching it twenty years later following the Covid pandemic certainly adds an edge of realism to a film that was shot with the intention of stripping away the fictive, often stylised elements that you get in 28 Days Later or even Children of Men.

The extended silent opening credit sequence on a black screen is unsettling, particularly as the action starts with a conventional, if murkily shot, scene of a family arriving at their holiday home in the forest. It takes some time to adjust to the lighting in what initially feels like a low budget shoot but you are soon brought up short. A synopsis of the plot may sound pedestrian: following an unexplained disaster a middle class family are assaulted, left wandering the countryside in search of assistance and supplies, and after a number of trials on the way, eventually find a community where people – at least some of them – are living in hope. But this is a Michael Haneke film and while the narrative may seem straightforward, the atmosphere is closer to Louis Malle’s Black Moon.

That murky aesthetic is important. The film was shot with natural light and in the many dark and obscure scenes, sound is often the only reliable indicator of action. The grim colour palette adds to the realism and importantly, the restriction of information is compelling; in much the same way as a horror film builds tension by obscuring the antagonist. This is not a film where you can afford to let your attention wander. The two scenes involving fire are breathtaking and demonstrate the beauty that can be achieved with minimalism. This spartan approach is reflected in Haneke’s use of music. He is known for eschewing film scores in favour of diegetic sound and has stated that music is usually used to hide a film’s problems. Having directed a number of operas on stage he knows what he is talking about, and in a particularly bleak moment of the film we hear a passage from Beethoven’s Spring Sonata that, though played on an old cassette tape, hints that there is value in hope.

The original meaning of apocalypse of course is ‘revelation’ or ‘disclosure’ and in Time of the Wolf Haneke draws back the veil, allowing you to see a cinema stripped of its usual fripperies. What is left behind is the ‘Real’, the concept described by Lacan.

“The Real is reality in its unmediated form. It is what disrupts the subject’s received notions about himself and the world around him. [...] as a shattering enigma, because in order to make sense of it he or she will have to [...] find signifiers that can ensure its control.” — Judith Gurewich

Encounters with the Real are supposed to be traumatic and that may be the actual purpose of a post-apocalyptic film as Haneke sees it. And we see the grasping at signifiers in the scenes at the train station, with attempts to impose order on the chaos; setting up of rules and norms within the station with decidedly mixed results. Meditations on human nature and violence are classic Haneke themes and are revisited here with race and class tensions threatening to rupture any sense of community.

Time of the Wolf has a noteworthy cast including Isabelle Huppert, Patrice Chéreau and Béatrice Dalle. Huppert maintains that habitual sang-froid, which has become so familiar, in the face of horrific and harrowing events. She starts as the lead of this ensemble but the focus shifts to the three outstanding performances of the children: Eva (Anaïs Demoustier), Ben (Lucas Biscombe), and the unnamed hard-bitten yet vulnerable survivor played by Hakim Taleb. I should point out that the industrious Ms Demoustier has appeared in more than 50 films since Time of the Wolf. As was the case with Funny Games and Hidden, whereas many directors tend to avoid children in film, Haneke often gives them a central role – perhaps their naivety offers hope in the bleak terrain of his worldview.

So is Haneke really so pessimistic about humanity? The title of the film comes from the Old Norse poem Völuspá, which describes both the creation and the end of the world. When all the Gods fall apart Odin is killed by Fenrir the great wolf:

Brothers shall fight | and fell each other,

And sisters' sons | shall kinship stain;

Hard is it on earth, | with mighty whoredom;

Axe-time, sword-time, | shields are sundered,

Wind-time, wolf-time, | ere the world falls;

Nor ever shall men | each other spare.

… which is actually a pretty good outline of the screenplay. The team were at odds in our views of the film’s meaning. Wolves usually live in packs and similarly, as the survivors gather at the train station the rules they establish for keeping order could be seen as leading to cohesion and a structure that is necessary if they are going to endure. But doesn’t the ‘Time of the Wolf’ signify a ‘dog eat dog’ ethos with the inevitability of societal breakdown? The acts of compassion here are individual: someone giving up some milk to an elderly couple, a young man playing music for Eva. And then the striking ending … a man who earlier attempted to lead a lynch mob rescues Ben from an act of self-sacrifice. Following the death of the Gods in Völuspá: ‘The earth will rise again out of the water, fair and green.’ Perhaps Haneke is no misanthrope after all?

And then … the final shot from a moving train. Passing through the countryside, sunlight on the trees. After the cataclysm a moment of transcendence redolent of Andrei Tarkovsky. Is this the future? Are our characters aboard? We don’t know, but it is the perfect ending. Another film would give us resolution but, “No,” says Haneke, “we cut here.” It is the Lacan in him, a hard stop in just the right place.

Reids’ Results (out of 100)

C - 80

T - 72

N - 75

S - 79

Thanks for reading Reids on Film. If you enjoyed it please share with a friend and do leave a comment.

Wonderful read!