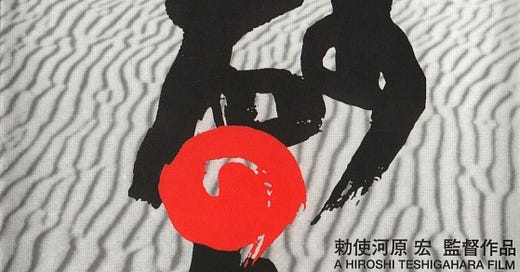

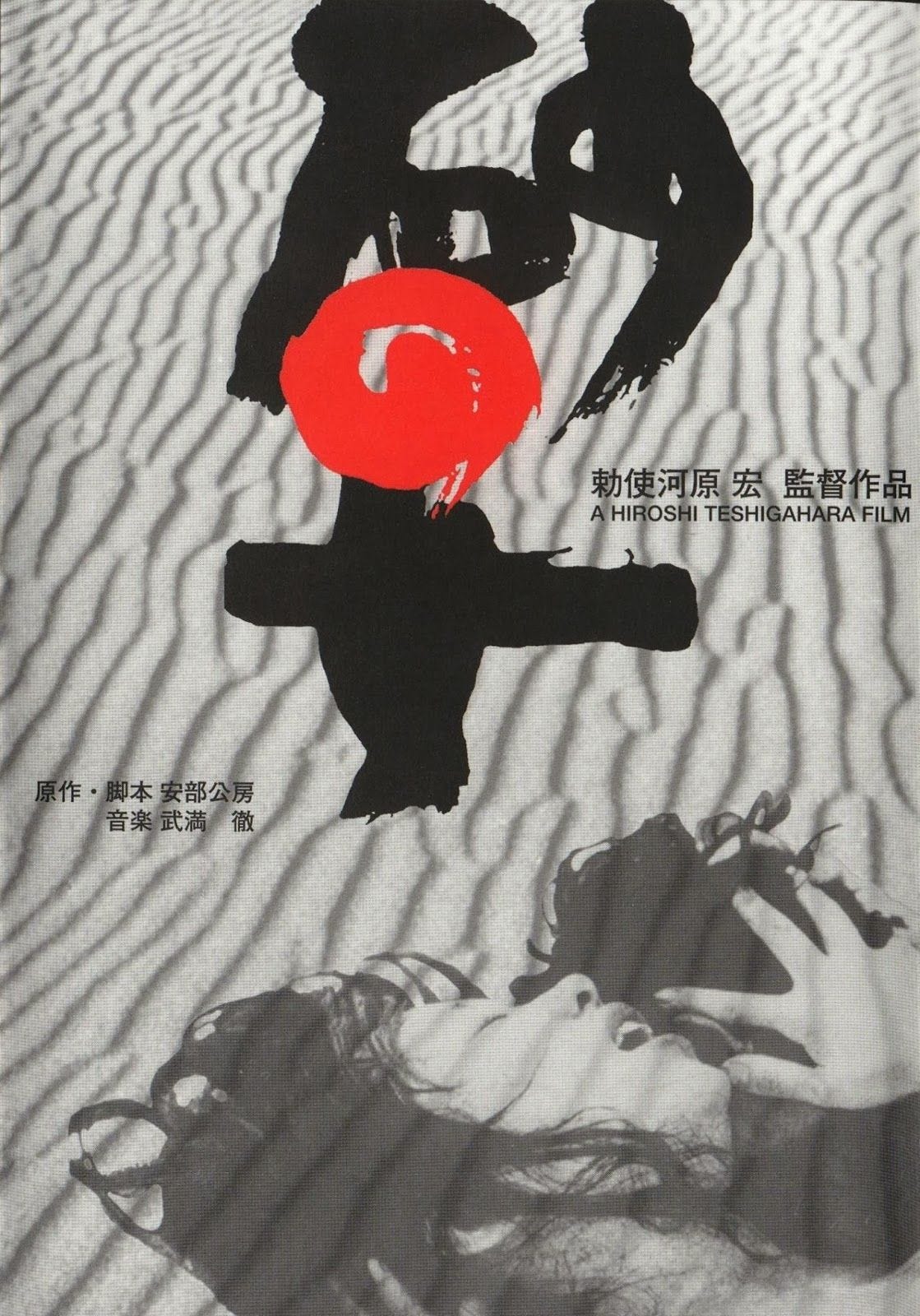

Directed by Hiroshi Teshigahara

Japan, 1964

🎁 ❄️ 🎁 ❄️ 🎁 ❄️ 🎁 ❄️ 🎁 ❄️ 🎁 ❄️

A quick reminder: ReidsonFilm are consulting with our subscribers for a Xmas film to review. One week left to submit your suggestions, otherwise we will end up with Love Actually. Drop your recommendations in the comment box below.

And this week’s review includes a personal take by N, which you can hear by clicking on the audio clip at the end.

🎁 ❄️ 🎁 ❄️ 🎁 ❄️ 🎁 ❄️ 🎁 ❄️ 🎁 ❄️

Woman in the Dunes opens with an impressive title sequence. It reminded me of one of Alfred Hitchcock’s masterpieces, and like Hitchcock’s greatest works Woman in the Dunes is a psychological thriller, but itself open to multiple interpretations. Yet it is also a very Japanese film.

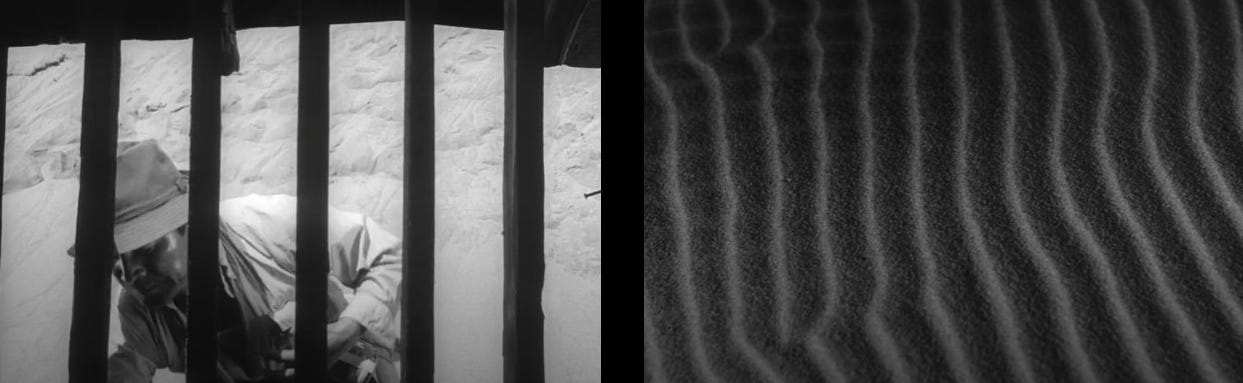

Going back to those opening credits, cast and crew names are revealed through fissures opening up across the screen. The soundtrack is an urban one – we hear cars and trains, a public-address announcement, we are in the city. Then a strange crystalline image fills the frame. The camera pulls back, revealing a pile of these shapes, not crystals but rocks? And then, we realise these are grains of sand – sand making up dunes in a desert landscape (yes, another film opening in the desert).

So a long way from the city then. We are introduced to a schoolteacher and amateur entomologist collecting insects in the remote wilds of Japan. He is trapped after missing his last bus home and some local villagers offer him shelter for the night. It turns out this is with a woman who lives at the bottom of a ravine in the sand:

“Hey, you old hag! Whatcha doin'? You've got a guest”.

He must use a rope ladder to reach her shack. The following morning, he wakens to find out that he has been tricked. The ladder has vanished and the walls of the ravine are made of crumbling sand. There is no way out, and then the woman reveals that this was indeed a trap.

He is expected to stay with her and help shovel away the sand that constantly blows and rains into the pit. She explains,

“If we stop shovelling sand the house will get buried. If we get buried the house next door is in danger”.

The sand is hauled to the surface by the villagers who sell it to make bricks for construction. So a simple, spare premise but with Woman in the Dunes, directed by Hiroshi Teshigahara and based on a modernist novel by Kōbō Abe, you will find yourself drawn, just like the entomologist, into a quagmire. But where his quagmire is one of quicksand, for the audience it is a fever-dream of existential despair, claustrophobic tension and stifling eroticism. The story unfolds over two and a half hours, and shot in one location with a small ensemble cast but it is compelling viewing.

Woman in the Dunes is one of four films that Teshigahara adapted from the books of Abe. He collaborated with an experimental composer Tōru Takemitsu and his cinematographer, Hiroshi Segawa, to create an alien – almost lunar – landscape in the desert. Teshigahara was an artist who worked in pottery and that influence is clear in the way that he moulds the landscape, lending it a sculptural beauty.

That imagery combined with the discordant score creates a symbolic prison and an atmosphere of entrapment. Traps feature a lot here: the entomologist setting traps for the insects – later he sets a trap for a crow that may help him to escape the trap that he finds himself in.

Woman in the Dunes also focuses on the body: the sand-encrusted bodies of the entomologist and the woman mirror the desert landscape. We know that in Japanese culture, you remove your shoes before entering a house maintaining that distinction between the dirty, impure outside and the home. That is an impossible task here as the sand seeps everywhere. The insect collector (Eiji Okada) moves from rage to despair, then finally acceptance, and over time the relationship between the two protagonists changes.

The woman (Kyôko Kishida) is a young widow, whose husband and child were lost in a sandstorm. Despite her age the villagers know her as the ‘Old Hag’, but perhaps inevitably their enmeshed situation overwhelms them, and the erotic undercurrent eventually reaches a climax. But this is no romance… this is a brutal, almost bestial union.

The man’s identity changes too – his name is not revealed until the film’s epilogue. At first, he is referred to as the Teacher, but once trapped in the dunes he becomes the Helper. Finally, the villagers know him as ‘the Husband’. He begins the film kitted out in all the gear you would expect of a city-dweller venturing into the wilderness, anxious to maintain his clean-shaven mien but by the end he has donned a kimono and looks just like one of the village men.

Their universe is confined to the walls around them, and their focus: somewhat ironically, selling sand with such a high salt content that any buildings made will eventually collapse. The sand is the source of their sustenance – the villagers only provide food and water if they deliver – but also their prison.

…like capitalist ideology and the digging of the sand. I think the sand clearly stands in for capital. It’s their income but also their prison, the thing that holds them in place and seeks to betray them at every possible opportunity. The sand acts with a will of its own amorphous, yet omnipotent, slipping through their fingers one minute and crashing down on your roof the next - C

Inevitably though, you will fall back on the most conspicuous reading, Camus’ philosophy of the absurd. For what allegory could this be, but a variation on the Myth of Sisyphus: a man is condemned by the Gods to spend eternity rolling an immense boulder uphill, only for it to roll back down, and so it goes on ad infinitum. Is the futility of the collector’s labours in the sand any different from the mundane existence of his city life?

There is one scene – which could have come straight out of a Ben Wheatley film – where the villagers offer the man a brief visit to see the ocean, but only if they can watch him having sex with the widow. They circle the pit wearing grotesque masks and carrying torches, toying with the pair just as the Gods were once wont to do.

Then one day, the woman is in acute distress. She may be having a miscarriage and the villagers take her to a doctor. They leave the rope ladder in place. The entomologist climbs out of the pit: freedom is in sight. He wanders for a while before coming up upon his earlier footprints. He’s been walking in circles. He returns to the pit and climbs back in, “…there’s no need to run away just yet”.

And here is N’s take:

Reids’ Results (out of 100)

C - 84

T - 88

N - 80

S - 83

Thank you for reading Reids on Film. If you enjoyed it please share with a friend and do leave a comment.

Coming next… The Conformist(1970)