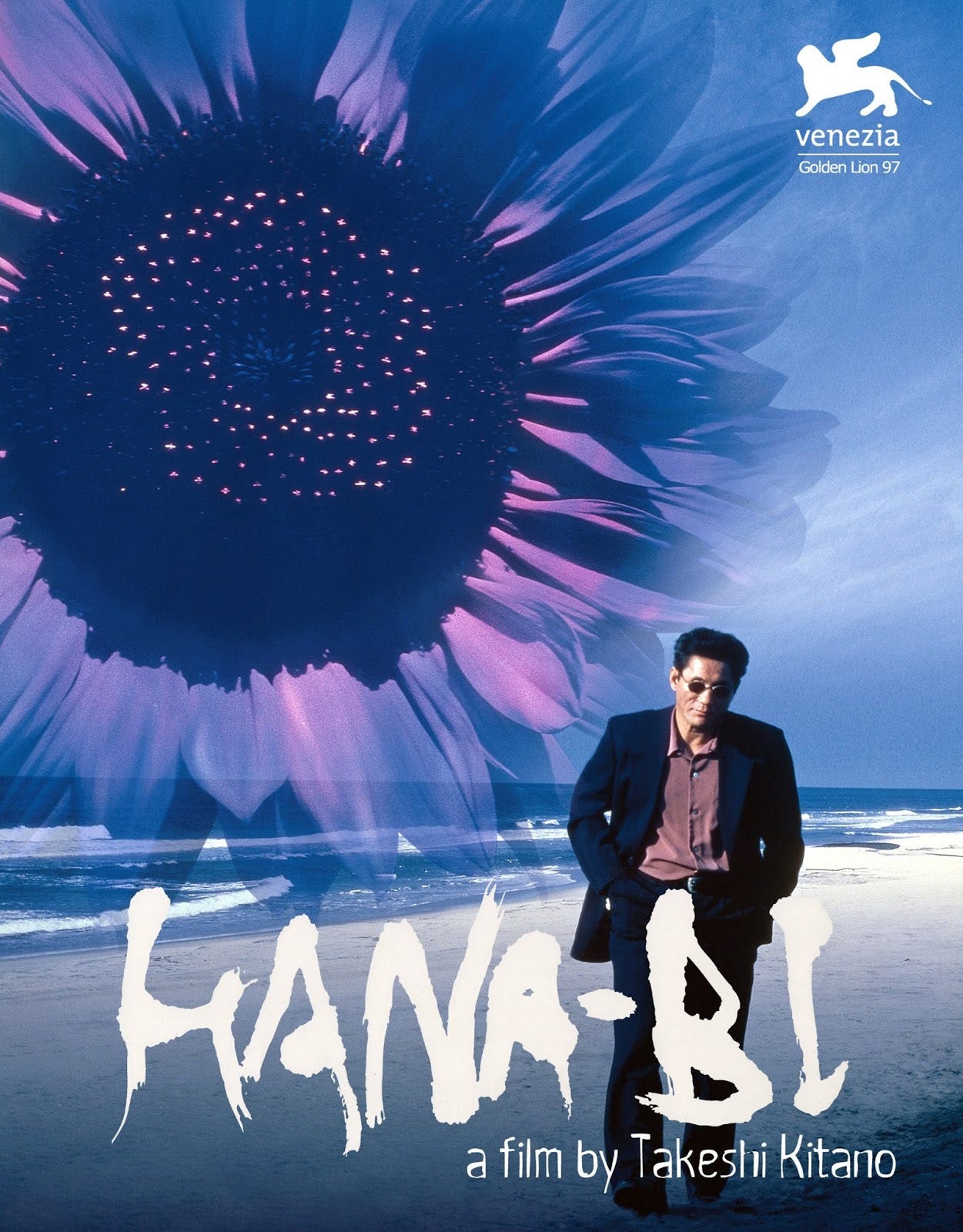

Directed by Takeshi Kitano

Japan, 1997

Who would have thought that the man behind Takeshi's Castle - the most absurd, wacky gameshow I have seen on broadcast TV - could produce such a deliberate, meditative tragedy - N

Hana-bi: Hana means flower, and Bi means fire. Put the two words together and you have fireworks. There are plenty of fireworks to be seen both literally and metaphorically in this film by TV host, comic, writer, editor, and musician, Takeshi Kitano.

Kitano plays Detective Nishi, a seasoned police officer, who starts the film in the most testing of circumstances. He has recently lost his daughter, and his wife is terminally ill with leukaemia. Nishi dips out of a police stakeout to visit his wife in hospital, and as he does so, his partner and best friend, Haribe (Ren Ôsugi), is shot and left paralysed by their target. Nishi, with two junior officers, catches up with the assailant in a busy shopping mall and in the resulting shootout one of the cops is killed.

Nishi leaves the force to look after his wife and, after a diversion involving a bank robbery to pay off his debts to a Yakuza boss, he heads off on a final picaresque adventure with his wife, Miyuki (Kayoko Kishimoto).

Nishi is the archetypal antihero, ruthless and at ease with extreme violence when required, but equally capable of humanity, shown most clearly in his relationships with his wife and his friend Haribe: the two emotional anchors of the film. But your prior expectations of a gangster film – especially if you are familiar with Kitano’s earlier yakuza trilogy: Violent Cop, Boiling Point and Sonatine – will soon be swept aside. There are no clichés to be found here.

Hana-bi is light on stylisation: scenes are shot with a static camera, and the framing is centred and functional - echoes of Yasujirō Ozu. Paired with this, the sound mix is reserved, casting a quiet, haunting atmosphere that mirrors Nishi’s detachment from the world around him. That taciturnity is mirrored again with Miyuki, who remains mute until she utters the final words of the film: arigatō, ‘thank you’. Dressed in a red baseball cap and blue windcheater she could be a character from a film by the animator, Hayao Miyazaki At times Hana-bi has the wistfulness of films like Spirited Away. That feeling of being suspended in time owes a lot to the score, written by the Studio Ghibli composer, Joe Hisaishi.

When I write a script, I have the entire film in my head, so when we start shooting, I just do it. I’m more interested in the editing process, so I tend to shoot in a hurry. Maybe you don't always have enough footage, but how you play around with it, is what is interesting - Takeshi Kitano

Kitano edits Hana-bi so that the narrative is fragmented – looping backward and forward in time. There are long passages of meditative quietness, then a hard cut to a burst of graphic action that generates an extraordinary tension. A chopstick is jabbed into an eye with explosive fury. An existential tragedy, but by no means ponderous, Hana-bi repeatedly veers off into slapstick comedy. It comes as no surprise, given his background, that the use of offbeat humour is a Kitano characteristic, and it works well here: Nishi and Miyuki on their the final road trip episodically dissolve into laughter, revisiting happier times.

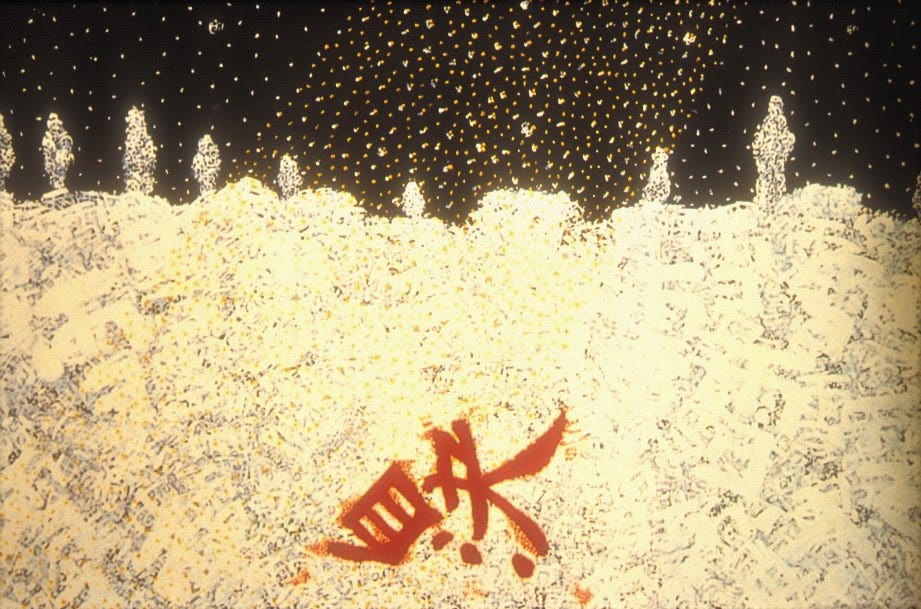

This may be Kitano’s most personal film. It was his first film playing a lead role following a motor scooter accident in 1994. He sustained a fractured skull and brain contusions, emerging from intensive care with a partial facial paralysis. That is evident here in his moments of laconic stillness, interrupted only by a facial tic. Having been abandoned by his family, and facing the prospect of life in the wheelchair, Haribe now lives in silent despair. He sublimates his suicidal thoughts by taking up painting. These surreal artworks often form the transition between scenes.

Surely inspired by Kitano’s own life experience, Hana-bi asks that most challenging of questions… how to continue living in the face of so much individual and collective pain? The film’s artwork is, of course, all by Takeshi Kitano. He taught himself to paint during his recovery.

Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms - to choose one's attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one's own way – Victor Frankl

Reids’ Results (out of 100)

C - 74

T - 85

N - 78

S - 87

🎁 ❄️ 🎁 ❄️ 🎁 ❄️ 🎁 ❄️ 🎁 ❄️ 🎁 ❄️

All I want for Xmas … is a ReidsonFilm subscription. Click here to give that Xmas gift.

🎁 ❄️ 🎁 ❄️ 🎁 ❄️ 🎁 ❄️ 🎁 ❄️ 🎁 ❄️

And feel free to drop us a note here:

Coming next… High Life(1997)