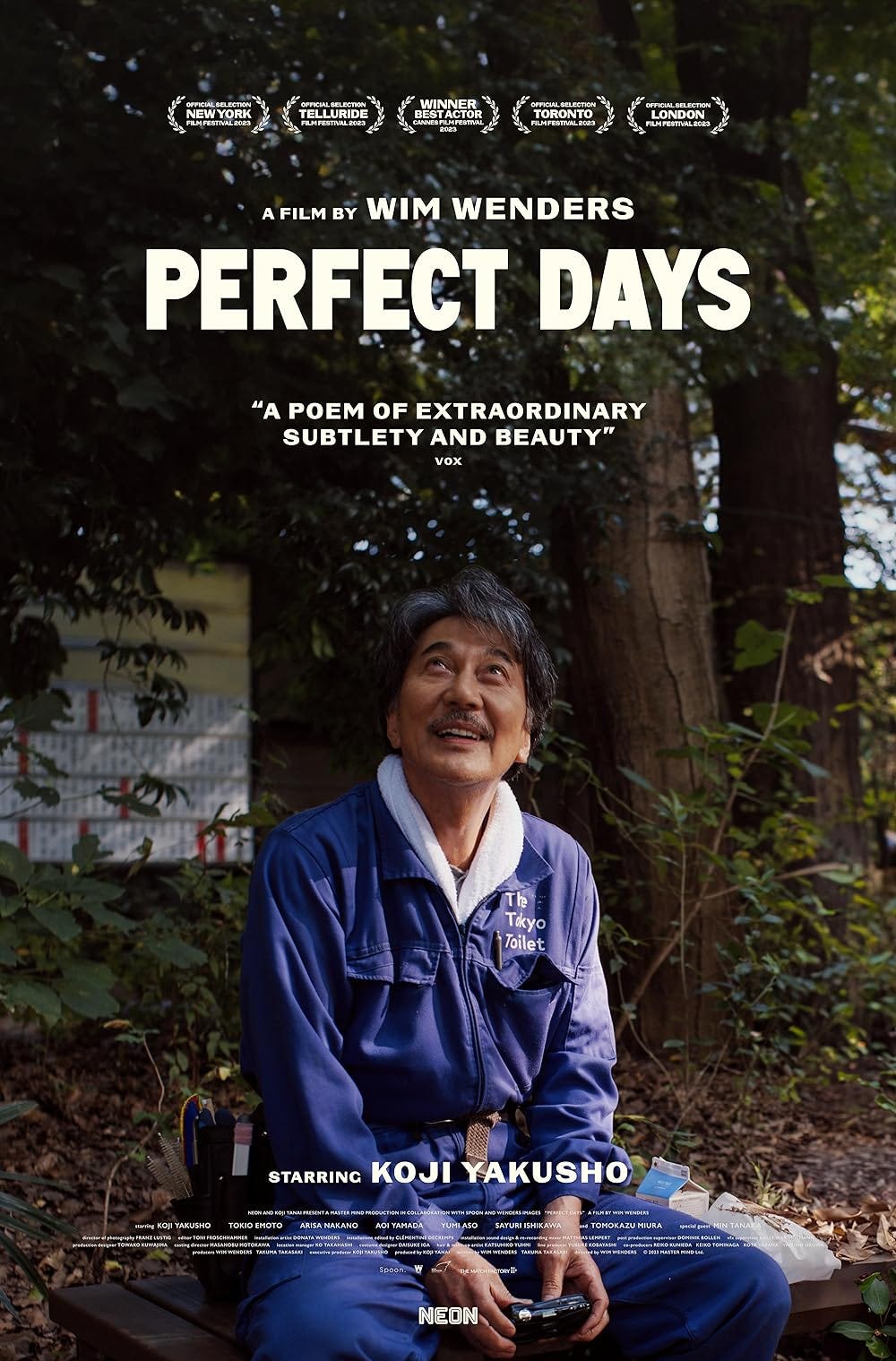

Directed by Wim Wenders

Japan & Germany, 2023

Yet another week in which ReidsonFilm find themselves at odds with each other. Perfect Days is the latest film by German auteur Wim Wenders, and somewhat ironically what could be titled Mindfulness: The Movie turned out to be a firework that has blown up the ReidsonFilm relations.

Ostensibly a film of simplicity, Perfect Days follows the daily routine of Hirayama (Koji Yakusho), a toilet cleaner in Tokyo, from dawn to dusk. And it is a routine. His days are repetitive and unchanging. He wakes up, prepares for the day ahead, listens to music as he drives to work, and then meticulously scrubs away at sinks and toilet bowls. But these toilets are no ordinary toilets. The Tokyo Toilets are the real life result of a project in Tokyo’s Shibuya district where seventeen new public toilets were created by architects and designers. Wenders was originally hired to make a short promotional film for the project, before it evolved into a narrative feature. The toilets are literally works of art and not the dirty, malodorous places we are used to. But that doesn’t stop Hirayama using a mirror to check the undersides of the toilet bowls to ensure that even unseen services remain spotless.

That is the core of his day, but Hirayama does find time to notice the world around him: trees blowing in the wind, light reflecting on surfaces. He takes photos of these scenes and methodically files the pictures away. Perfect Days is a meditative film, although never dull. How much Wenders is presenting his protagonist’s lifestyle as a cause for celebration, set against a critique of 21st century living, is open to question. But there does seem to be an argument here for a different way of life. Hirayama lives a stripped back existence combined with a retrophilia. He is resolutely fixed upon a back-to-basics rejection of the digital age. Those photographs are all developed from a roll of film in a lab. No camera phone for him. We find out later that Hirayama does possess a mobile, a flip phone, and I doubt that it’s smart. He buys real books from a second-hand bookshop, and his music? Cassette tapes of course…

The irony is that for a man living an ascetic, spiritual lifestyle, he has like the most algorithmically-perfect, second-year college student who just bought a vinyl player from Amazon, musical taste - it’s like the most bait song choices every time - name the artist and the first song that comes to mind is the song he’s playing: Lou Reed, Van Morrison, The Kinks, and so on - C

Hirayama’s routine is not without incident or intrusion. For a while he has a Gen Z co-worker who sees little value in cleaning lavatories, but a lot of value in those cassette tapes that are worth a lot of money in contemporary Tokyo. More intrusive is the arrival of his niece who has run away from home. She stays with him for a few days, eventually joining him in his labours. Her visit also shines a light on his backstory, a suggestion of a past involving wealth, status, and now estrangement from his family. His world is briefly knocked off its axis but Hirayama soon adapts, the turbulence in his life soon flattens into stillness, like ripples on a pond.

The narrative is also interrupted by impressionistic, abstract, black and white dream sequences – a rare foray into the metaphysical – drawing on the Japanese concept of komorebi.

Komorebi: the shimmering of light and shadow created by leaves swaying in the wind.

The cinematography is naturalistic, often only using available light, but capturing the beauty of his environment. Tokyo’s Skytree tower frequently appears in the cityscape mirroring the seedling trees that Hirayama mists every morning in his apartment. It is also noteworthy that the film is shot in the increasingly fashionable 4:3 aspect ratio… another call back to the retro.

But are Hirayama’s days really that perfect? And if not, was that the director’s intention? Wender’s portrayal of Hirayama’s way of living was, like those Tokyo toilets, just too squeaky-clean for one or two of ReidsonFilm. Questions about his interests and motivation are left unanswered, they are as opaque as his dreams. A man of few words, he remains something of a cipher. Wenders gives us little sense of Hirayama’s interior life other than through signs in the world he inhabits, a marked difference from the characters that people the films of Yasujirō Ozu. Perfect Days has been compared to the deliberative minimalism seen in Tokyo Story and Late Spring (ReidsonFilm review) but while Ozu has an obvious curiosity about people and their relationships, with Wenders these questions are more ambiguous.

Wim Wenders: We left it very much to the audience to somehow piece Hirayama’s earlier life together. In a more conventional film, you would have certainly found out all about it.

For a supposedly naturalistic film, the whole premise strained credibility. And for someone on the path to enlightenment, Hirayama was collecting a lot of ‘stuff’ in his apartment. This is Zen Porn – S

I can only wonder how ‘present’ you were while watching – N

Despite our differences ReidsonFilm were agreed on the exquisitely humane performance by Koji Yakusho. The actor makes the film worth watching. His face is like an artist’s canvas, giving Perfect Days a sense of authenticity, together with his ability to externalise his happiness, pain, frustration, and pleasure. No more so than the extended close-up shot of Hirayama as the film ends. Driving his car as he listens to Nina Simone, his expression cycles though joy to anguish, tracking that final scene from The Long Good Friday (ReidsonFilm review) as Harold Shand (Bob Hoskins) realises that he is soon to meet his end. It is in this sequence that the film's ideas culminate with a genuine doubt for both the audience and Hirayama himself. Does he regret his decision to walk this simpler path?

Hirayama: Next time is next time. Now is now.

Reids’ Results (out of 100)

C - 74

T - 71

N - 80

S - 65

Thank you for reading Reids on Film. If you enjoyed this review please share with a friend and do leave a comment. By the way, Toilet no Kamisama, the sub-heading for this review translates as ‘God in the Toilet’.

Coming next… Jane B. for Agnes V.(1988)