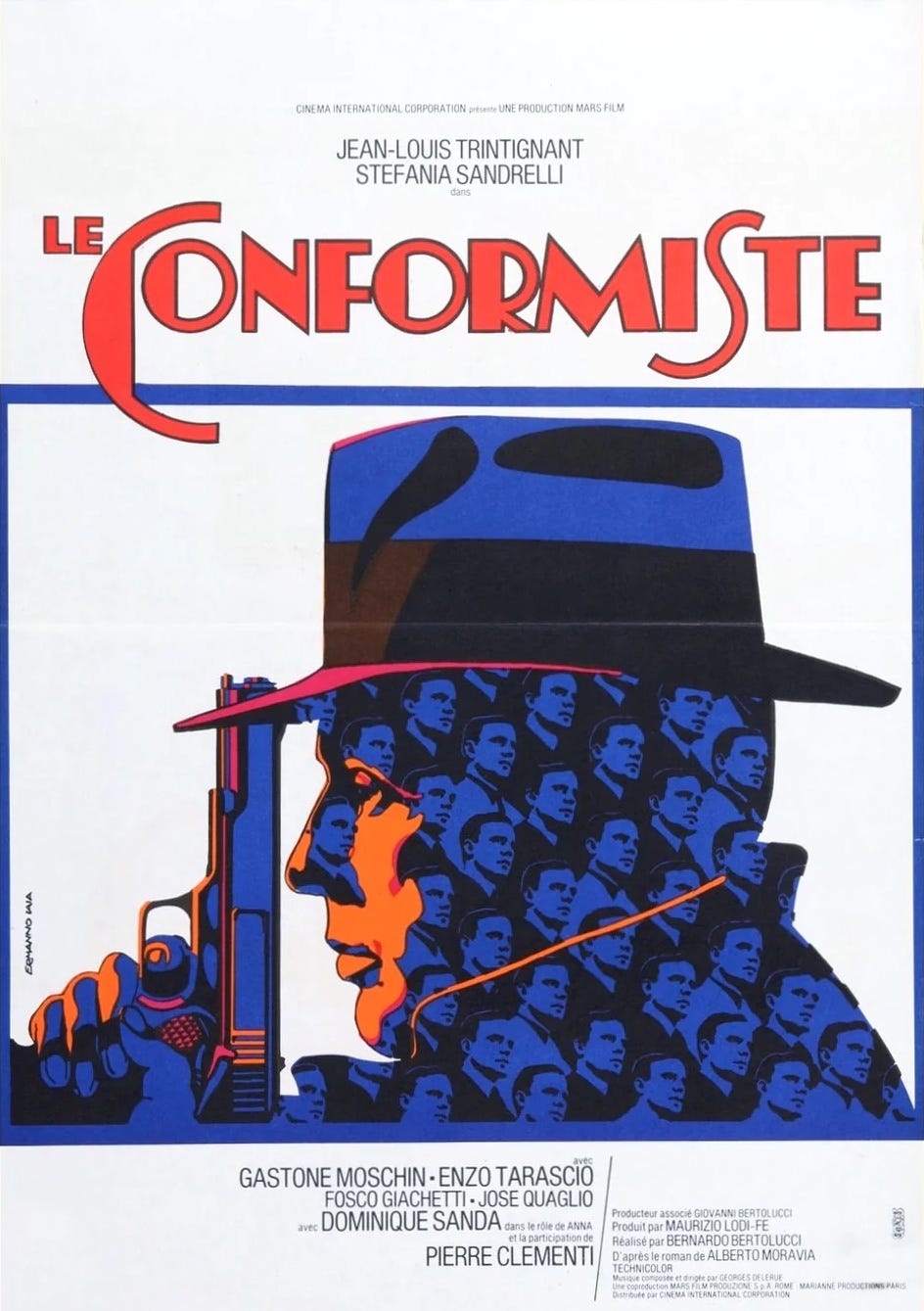

Directed by Bernardo Bertolucci

Italy, 1970

We have seen some films with real visual flair in this season of ReidsonFilm but I think it would be hard to find a film that surpasses the late Baroque style of The Conformist.

There is a richness to this film, with its luscious colour palette and sweeping but precise camera movements, that will seduce you. We have seen it before in the Italian cinema of Fellini, Visconti, and more recently Paolo Sorrentino, where the decadence drips from the screen. The expressionist design harks back to the past, reminiscent of the monumental sets of Welles’ Citizen Kane, but also – and this is intriguing – to the future. ReidsonFilm recently reviewed David Lynch’s Inland Empire and it’s hard to escape the allusions in Lynch’s work, notably with Mulholland Drive.

The artistry of The Conformist is the work of a triumvirate: director Bernardo Bertolucci in collaboration with the cinematographer Vittorio Storaro, and Ferdinando Scarfiotti in charge of production design. All in their late twenties they clearly had that fearlessness and sense of adventure that you see in the early Orson Welles. Storaro would go on to shoot Apocalypse Now and they would each win an individual Academy Award for their work on Bertolucci’s The Last Emperor. It is difficult not to lose yourself in the stylish sophistication of shots like this:

And then the gear changes to noir-expressionism and the hypnotic surrealism of dream-logic.

But what of the story? Based on a 1947 novel by Alberto Moravia The Conformist is set in 1930s Italy and focuses on the journey of the upper-class Marcello Clerici (John-Louis Trintignant). He joins the OVRA, the secret police of Mussolini’s fascists. His motive? Not driven by politics or ambition, Clerici simply wants to fit in. His desire – at least the one that he acknowledges – is to be normal, a colourless member of the bourgeoisie. To this end he marries the beautiful but guileless Giulia (Stefania Sandrelli).

Friend: What do you think marriage will get you?

Clerici: I don’t know. The impression of normalcy

Friend: Normalcy?

Clerici: Yes. Stability, security. In the morning when I’m dressing in the mirror I see myself. And compared to everyone else I feel different.

The narrative unfolds with a series of Chinese boxes – a complex chain of flashback within flashback. The film actually takes place over the course of a single long car journey: Clerici is on his honeymoon but he is also on a mission. Initially his task was to track down his old Marxist philosophy professor and inform on him and his contacts, but the plan has changed and now assassination is the goal.

Throughout the film Bertolucci’s mastery of the mise-en-scène serves to unsettle the viewer, tilting the frame and using discontinuity in the editing. And there is, of course, the chiaroscuro – that contrast between light and shadow. In one scene Clerici has a conversation with the professor about the allegory of Plato’s Cave.

A group of people are chained together inside an underground cave as prisoners. Behind the prisoners there is a fire, and between the prisoners and the fire are moving people and objects. However, the prisoners are unable to see anything behind them, as they have been chained and stuck looking at the cave wall for their whole lives. They can only look at the shadows cast on the wall and that is what they believe real life is. Their visible world is their whole world. Is there a better metaphor for the relationship between cinema and its audience?

That contrast between light and dark represents the divide between the conscious and unconscious. Freud looms large here, and that’s where the cracks begin to show. The Conformist is a film of the 1970s, a period when unearthing psychological motives for all of our actions was a repeated theme. The drive for Clerici to conform – to conform with fascism – originates in an episode from his youth: he is sexually abused as a boy, and then shoots his abuser (or so he believes). As a consequence he is forever spoiled and sublimates this trauma by seeking to fit in.

In a masterful performance, Trintignant plays Clerici as if he were Kafka’s insect, Gregor Samsa from The Metamorphosis, a stiff, scuttling character careful never to step out of line. He exists through projection, projecting his unacceptable urges onto the people in the world around him. Notably, he falls for Anna, the alluring wife (played by Dominique Sanda) of the professor, who in turn makes advances toward Giulia. Sanda then appears in a different role later on as a prostitute.

Yes, it is clear that Clerici is confused about sex. Political extremism comes from sexual neurosis – these hackneyed psychological theories look dated now, or perhaps not? A more obvious motivation for his will to conformity may be that his ‘syphilitic’ father is confined to an asylum, and his opiate-addicted mother spends all day in bed sleeping with her chauffeur.

So, perhaps a film of more style than substance, but oh what style! So many scenes that you want to watch again and again: for example, the classic tango sequence involving Giulia and Anna.

Clerici’s spineless impotence is finally revealed in the film’s operatic climax, and then the ending: following Mussolini’s downfall, we watch as Clerici denounces friend and foe. And a final glance, a look over his shoulder, a haunting look of longing, both into his past and into his future.

A Godfather-Lynch-Fellini remix: the way it fuses genres and brings wild ideas together and seems to break rules - C

Reids’ Results (out of 100)

C - 76

T - 74

N - 80

S - 73

🎁 ❄️ 🎁 ❄️ 🎁 ❄️ 🎁 ❄️ 🎁 ❄️ 🎁 ❄️

Xmas Film: So after a snowstorm of suggestions for the ReidsonFilm Xmas movie, three films topped the chart. Three very different films, perhaps reflecting our subscribers’ ‘wide-ranging’ tastes. We have (1) the Arnold Schwarzenegger comedy vehicle, Jingle All the Way, (2) a John Waters production, Female Trouble, and (3) the classic yuletide musical, Meet Me in St Louis, starring Judy Garland.

Which one would you choose? Let us know - yours may be that swing vote:

🎁 ❄️ 🎁 ❄️ 🎁 ❄️ 🎁 ❄️ 🎁 ❄️ 🎁 ❄️

Thank you for reading Reids on Film. If you enjoyed it please share with a friend and do leave a comment.

Coming next… Hana-bi(1997)