Directed by Ida Lupino

United States, 1953

What do Nicolas Cage and Werner Herzog have in common? They were both featured in the first ReidsonFilm review. The film: Bad Lieutenant - Port of Call New Orleans. One year later we are still here, cranking them out, one week at a time. Tonight we will be celebrating our first anniversary and wanted to say a thank you to all of our subscribers, both old (you know who you are) and new. For new subscribers, if you want to find out who we are press this button:

Film Noir: a style or genre of cinema marked by a mood of pessimism, fatalism, and menace. The term was originally applied (by a group of French critics) to American thriller or detective films made in the period 1944–54.

Cynical – yes, menacing – sure, pessimistic – absolutely. The Hitch-Hiker is a noir classic that is spare and lean, with not an ounce of fat in its 70 minute running time. The film opens with two cars: one being driven by a killer on a murder spree, the other has two old army pals, Roy Collins (Edmond O’Brien) and Gilbert Bowen (Frank Lovejoy), setting off for a few days together to escape the ties of work and marriage. They tell their wives that they are going hiking in Arizona’s Chocolate Mountains, but they are actually heading down to Mexico for a fishing trip, and perhaps a little racy nightlife in Mexicali. As they head out of town, they pick up a hitchhiker. It turns out that it is the killer, Emmett Myers, who forces them down to the border at gunpoint and then on a desperate ride into the Mexican desert.

The Hitch-Hiker, was inspired by the true-life story of Billy Cook, a man who in 1950 murdered six people on a three week rampage from Missouri to California, while posting as a hitchhiker. The film’s director visited Cook in San Quentin Prison, interviewed him and persuaded him to resign a release so that she could fictionalise his story. Cook was executed in the gas chamber shortly afterward.

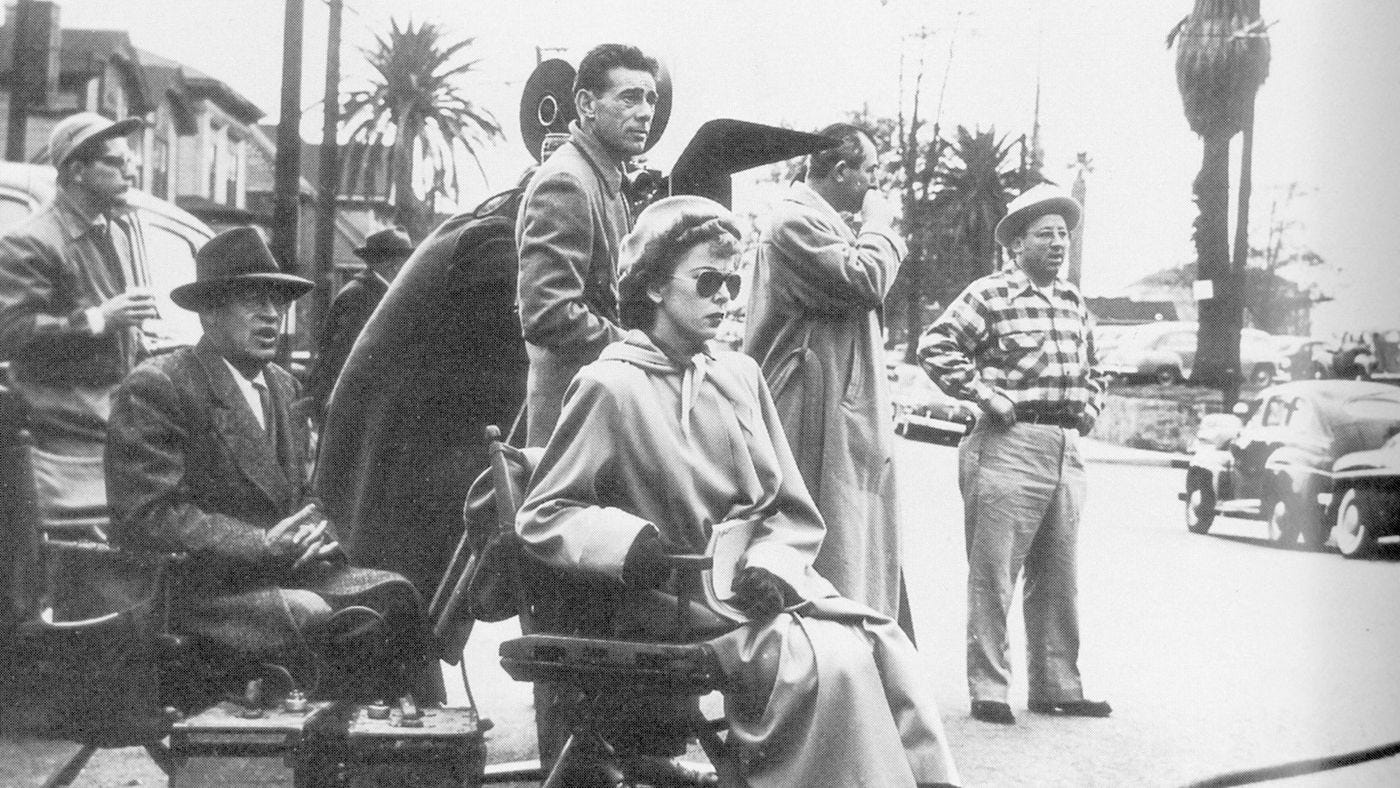

That director was Ida Lupino and she also co-wrote the script. Lupino was a pioneering, and arguably the most significant, female film-maker during the Golden Age of Hollywood. She hailed from South London (Herne Hill for you locals out there), and after acting in a string of British B-movies, she found success across the pond. As a contract actor Lupino famously referred to herself as ‘the poor man’s Bette Davis’.

Always keen on what happened on the other side of the camera she got her chance when the director of a film she was working on had a heart attack and couldn’t continue. Lupino never looked back, going on to forge a career in the 1950s as a radical director, shooting films that dealt with ‘social issues’ – what was at the time controversial subject matter: unmarried mothers, bigamy, and rape. It may be hard to imagine that the director of a bleak drama set in the rugged desert landscape grew up in a leafy London suburb, but then again look at Alfred Hitchcock (Leytonstone if you’re interested).

As a star, Lupino had no taste for glamour, and the same was true as a director: she wanted to “do pictures with poor bewildered people because that's what we are.” - Martin Scorsese

Compare Lupino with the European émigrés, such as Fritz Lang and Otto Preminger, who arrived in Hollywood in the 1920s, bringing German expressionism with them. She plays with, and subverts, the classic film noir tropes from the start. You sit up and take notice watching the opening montage of The Hitch-Hiker: anonymous murders, shots of the victims’ arms and legs – faces unseen – until the camera turns, and reveals a shimmering black revolver, pointing at us the audience, and then the face of the killer, Emmett Myers.

The Hitch-Hiker was shot on low budget, a trademark of post-war noir, but there was some debate in ReidsonFilm on whether this was a true film of the genre. Where are the oppressive cityscape, the chiaroscuro lighting, the jarring ‘off-centre’ camera angles? Lupino takes us out of the metropolis to the badlands of the Mexican desert, shooting on location with expansive wide-shots that accentuate that terrain’s hostile menace. This contrasts with the claustrophobic close-up shots in the car: Myers sitting in the back, shrouded in shadow. There is a feeling that Myers could explode into violence at any time – this is realism all right, no studio-set artifice here.

That pressure-cooker tension attention is ramped up masterfully by William Talman as Myers with a performance that almost steals the film. He has a malformed eyelid that does not close – as did Billy Cook – so when the three men camp out at night, Emmett’s right eye chillingly remains open. Collins and Bowen never know whether he is asleep or watching them.

What would you do in that situation?

T: I think I would have tried my luck with running at some point – there’s that seven metre rule, the distance you could cover with a weapon against a gun…

N: I thinks it’s easy as a viewer to claim how you would act heroically in that scenario – everyone has a plan until they get punched in the face.

The question of the passivity of Collins and Bowen shines a light on that other absent film noir staple - the femme fatale. In fact, this is a film devoid of women. The Hitch-Hiker is a searching character study of the three men. Collins and Bowen bicker about whether to confront Myers or go along with him in the hope of their eventual escape. Collins in particular feels unmanned by Myers, tormented by his sarcastic jibes about their buddy-buddy relationship and their domesticity:

You guys are soft. You’re scared to get out on your own. I got what I wanted my own way. When you get the know-how and a few bucks in your pocket, you can buy anything or anybody.

They are the three elements of one personality: the id, ego and super-ego. Myers obviously the primitive, aggressive id, Bowen the smart, moralising super-ego (he can read a map and is cautious about taking chances), and then Collins the ego, with his compromised masculinity, desperately trying to prove himself - S

That Trumpian statement illustrates Lupino’s subversion once again, but this time of the American Dream. After all, isn’t Myers with his sadistic, selfish individualism the ultimate capitalist? Inevitably though, fate catches up with Myers and as he is led away in handcuffs by the Mexican police Bowen and Collins walk slowly out of the dark shadows into the light. Bowen puts his arm around Collins and tells him:

It’s okay. It’s going to be all right.

The only unconvincing line in the movie, but we think deliberately so. Take a look at the expression on Collins’ face.

It’s an interesting dark perversion of the American ‘On the Road’ idyll of being able to go wherever you want and be whoever you want to be - C

Reids’ Results (out of 100)

C - 65

T - 70

N - 62

S - 72

Thank you for reading Reids on Film. If you enjoyed our review please share with a friend and do leave a comment.

Coming next… Suzhou River(2000)

I've got a film for you to review

The colour purple think in cinema 28th January

Not sure I'd enjoy watching this film 🙄🙄