Directed by George Sluizer

1988, Netherlands

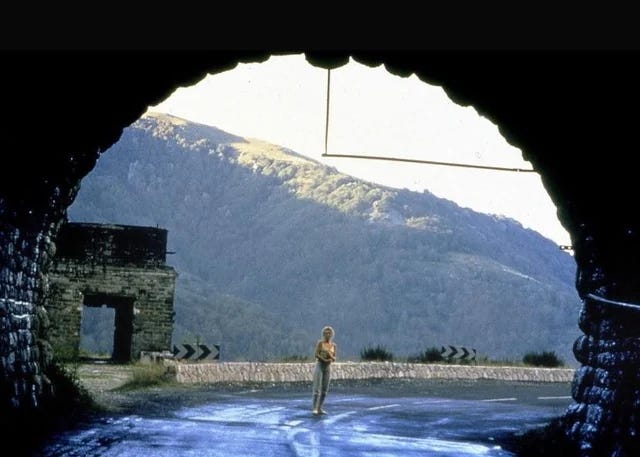

A young couple, Rex and Saskia, are going on a camping trip in the south of France. As they drive through a mountain tunnel Saskia tells Rex that last night she had a nightmare. It is a recurrent dream:

Rex: That you’re inside a golden egg and can’t get out, and you float through space all alone forever.

Saskia: Yes, the loneliness is unbearable. But this time there was another golden egg flying through space. And if we were to collide it would all be over.

The car runs out of petrol in the tunnel – Saskia had suggested that Rex refill it earlier. The couple bicker.

Rex: What got us here doesn’t matter. We just have to get out.

An articulated lorry passes, threateningly close. Rex (Gene Bervoets) accuses Saskia of becoming hysterical and storms off to get petrol. He leaves her alone, tearful, in the dark. When he returns, Saskia (Johanna ter Steege) has vanished but he finds her at the far end of the tunnel, bathed in light.

The two reconcile. That is Saskia’s first disappearance. Ten minutes later she disappears again, but this time for good.

The Vanishing is based on a novel, The Golden Egg, by Tim Krabbé. It begins like a typical thriller and to be honest it is packed with clichés: the female lead disappears earlier than Marion Crane in Hitchcock’s Psycho. What makes The Vanishing different though is that the director, George Sluizer, takes one of those clichés – killer explains himself rather than escaping, call it the Scooby Doo exegesis – and subverts it, extending it through much of the film.

So, a thriller with one of the most famous endings in cinematic history, a climax that may well leave you with nightmares, but that is not what makes The Vanishing so unsettling. It is Sluizer’s use of flashback and ellipsis, splintering the narrative, that builds up the sense of unease. Codes and symbols – a flattened cola can, egg-shaped photos of Rex and Saskia in the newspaper – are scattered through the film like a trail of breadcrumbs, foreshadowing what is to come.

That fractured narrative slowly reveals the story of the third man in our trio: Raymond Lemorne. He happens to be the killer, and an alternative title for this film could be Anatomy of a Murderer. We watch Raymond from his early years, growing up to become a chemistry lecturer. He marries and has a family. But all the while he is a psychopath hiding in plain sight. His mundane daily life is filled with obsessional rituals that we come to realise are actually preparations for his plan to abduct and murder a woman: testing out hypnotic drugs, rehearsing lines to lure a woman into his car. The trials are followed so closely, in patiently drawn-out takes, that you may start to identify with him. It’s a masterful performance by Bernard-Pierre Donnadieu, clinically detached and quietly controlling.

Three years after Saskia’s vanishing, Rex is stuck, unable to move on and still desperately seeking answers for her disappearance. Following a television appeal it is now that Raymond starts taunting Rex with postcards, suggesting that he will reveal her fate. Why does he do this? Is it simply narcissism or does Raymond perhaps see in Rex a reflection of his own obsessional drive?

The two men meet and Raymond promises to tell all as long as Rex agrees to ‘share the exact same experience’ that Saskia herself underwent. Why would Rex agreed to such a ludicrous proposal? That is the question at the heart of the film, overriding any question of justice or punishment. An existential dilemma: ignorance or knowledge – though knowledge at what cost?

The pair return to the south of France and on the long drive Raymond recounts the events leading to Saskia’s disappearance. Despite his meticulous planning, her abduction was ultimately a matter of chance, or was it fate? Rex listens, mesmerised, as Raymond takes him on a literal and metaphorical journey that leads to the film’s terrifying denouement. Yet what makes it so terrifying is that the ending we get is, perhaps after all, inevitable.

The director Stanley Kubrick called George Sluizer after seeing The Vanishing to tell him it was the most terrifying film he had ever seen. Sluizer was skeptical and responded, “But you directed the The Shining, haven't you seen that?” To which Kubrick replied, “Yeah, but that was child's play compared to this!”

Reids’ Results (out of 100)

C - 68

T - 77

N - 83

S - 73

Thank you for reading Reids on Film. If you enjoyed our review please share with a friend and do leave a comment.

Coming next… Caligula: The Ultimate Cut(2023)

As I recall, there was an American remake where the story has a happy ending

One of the most disturbing films I've seen!