Directed by István Szabó

Hungary, 1981

They say you wait ages for one film about a man who sells his soul to the Devil, and then two come along at once. Hot on the heels of last week’s review of Jan Švankmajer’s Faust, we now have Mephisto, another tale of diabolical double-dealing, directed by Hungarian filmmaker István Szabó in 1981.

Both films explore the Faustian bargain but in distinct ways. Obviously there is a contrast in cinematic styles – there are no puppets in Mephisto – but where Švankmajer’s Faust plays out in the aftermath of the collapse of a communist state, Mephisto is set amid the rise of another totalitarian regime, Nazism.

Szabó adapted Mephisto from a 1936 novel by Klaus Mann. I say novel, but the book was inspired by Mann’s brother-in-law (and former lover) Gustaf Gründgens. One of the most influential German actors of the 20th century, he enjoyed a meteoric career under the Third Reich.

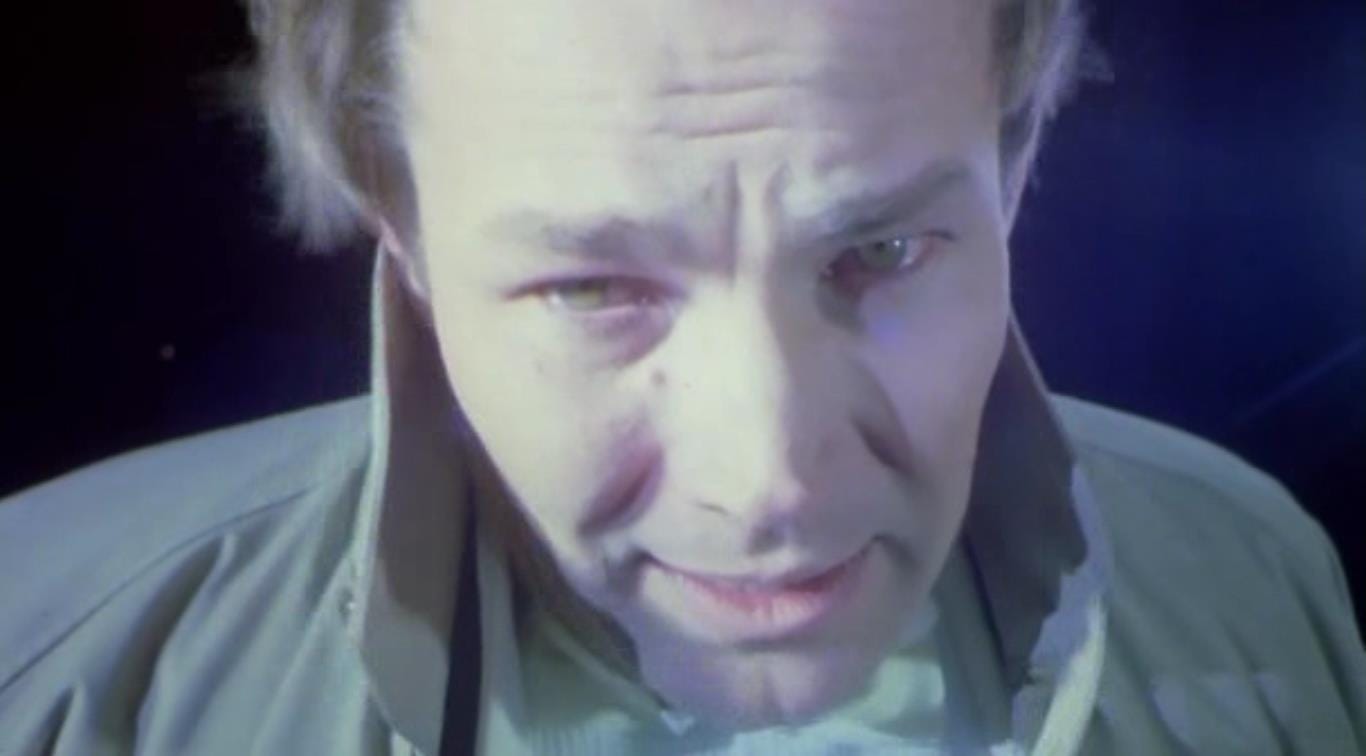

In Mephisto, Gründgens is reimagined as the character Hendrik Höfgen and as the film opens he is in the throes of a tantrum. A provincial actor in Hamburg, Hendrik is consumed with jealousy at the news that his leading lady is heading off to the bright lights of Berlin. In contrast to the subdued performance of Petr Čepek, as the protagonist in Faust, here we have the opposite, an extraordinarily physical and melodramatic performance by Klaus Maria Brandauer as Hendrik. Actually, that’s not quite right. Höfgen’s real name is Heinz but he upgrades it to Hendrik to appear more sophisticated:

My name is not my name – because I am an actor.

That is actor with a capital ‘A’.

Desperately ambitious, in Hamburg Hendrik proclaims that he is bringing a new theatre to the people, a Bolshevik theatre. Of course, the real revolution taking place in Weimar Germany, is that of National Socialism. But Hendrik’s radical politics are not convincing. His hollow posturing is just another means of drawing attention to himself. He marries a wealthy heiress from a liberal family, primarily to leverage her father’s connections in the Berlin theatre scene. An uber-narcissist, the only cause that Hendrik believes in is himself and his ambition.

The role that brings him acclaim, and draws the attention of the Nazi hierarchy is of course, Mephistopheles in Goethe’s Faust, performed in striking white make-up.

“How did you go bankrupt?"

Two ways. Gradually, then suddenly.” – Ernest Hemingway

Hemingway is talking about money here, but in Mephisto that line aptly describes Hendrik’s moral bankruptcy. Initially, along with his some of his theatrical coterie, the Nazis are considered a joke, not worthy of serious attention:

That Bohemian corporal … the Austrian clown has become Reich Chancellor

They will make sure he doesn’t get too big for his boots.

One evening as Hendrik leaves the theatre he witnesses a gang of Brownshirts beating up a Jew, his response is simply: “drunken idiots”. His fellow actors, friends, and family begin to flee the country but not Hendrik. During the interval of one of his performances as Mephisto, he is invited to the box of a high-ranking Nazi official, only ever referred to as ‘the General’ (reportedly based on Hermann Göring). As the audience falls silent to watch this highly charged moment – it’s another performance, the Nazi uniform is just as theatrical as Mephisto in his white face and red cape – Hendrik seals the deal, and his fate. Agreeing to serve the Nazi state, he will head the German State Theatre. The memory of his earlier flirtations with communism will be wiped away. No longer Mephisto, he has become Faust and so he begins his ascent... or descent into moral hell.

The legend of Faust has been portrayed countless times in art, particularly in film. However, István Szabó goes beyond a mere retelling or making loose allusions to the story in Mephisto. Instead, he critically examines the deeper implications of the complicity that Hendrik is all too willing to embrace.

In ReidsonFilm’s second season we reviewed The Conformist, by Bernardo Bertolucci, another visually stylish film that tracks the rise of fascism. However, while Bertolucci‘s film sees the protagonist’s moral failing as a symptom of his sexual neurosis and fear of being different, Hendrik’s wilful blindness to what happens around him, as he seduces his audience – yes, including us – presents a more provocative question: what are the moral compromises that we ourselves are prepared to make?

Central to the success of this film is Brandauer as Hendrik in a chameleon-like performance. One moment likeable, the next electrifying, then pitiable, then craven – greedily demanding that the camera hold his face in close-up. He betrays all the people in his life, including his lover, Juliette (Karin Boyd), a black dancer whom he naively tries to hide away in a Berlin apartment. This is no act of rebellion; outside of the world of the theatre, Juliette is the one person who sees Hendrik for who he really is. She recognises that their continuing relationship isn’t grounded in solidarity or moral conviction but on his sense of invulnerability - which we know will not last.

Because the Devil for Hendrik’s Faust is the softly-spoken, avuncular, Nazi General, who appears to be in awe of Hendrik’s strength as an actor but appalled by his weakness as a man – he repeatedly remarks on the limpness of his handshake.

When I hear the word culture, I reach for my revolver - The General

For all the opulence of the theatre, the grandeur of Berlin’s monuments, the luxury, and the ballgowns, the stench of oppression is inescapable, like a miasma. And through it all Hendrik remains in the flaring spotlight, right up until the film’s final moments. Then in the middle of the night, the General takes him to a monumental stadium, that exudes the aesthetic of Leni Riefenstahl. There, that spotlight forces him down into the arena floor where Hendrik is reduced to a self-exculpatory plea:

What do they want from me now? After all, I am just an actor.

That blinding light, a theatrical spotlight or the searchlight of a watchtower?

We are what we pretend to be, so we must be careful about what we pretend to be ― Kurt Vonnegut

Reids’ Results (out of 100)

C - 81

T - 80

N - tbc

S - 81

Thank you for reading Reids on Film. If you enjoyed our review please share with a friend and do leave a comment.

Coming next… Saturday Night Fever(1977)