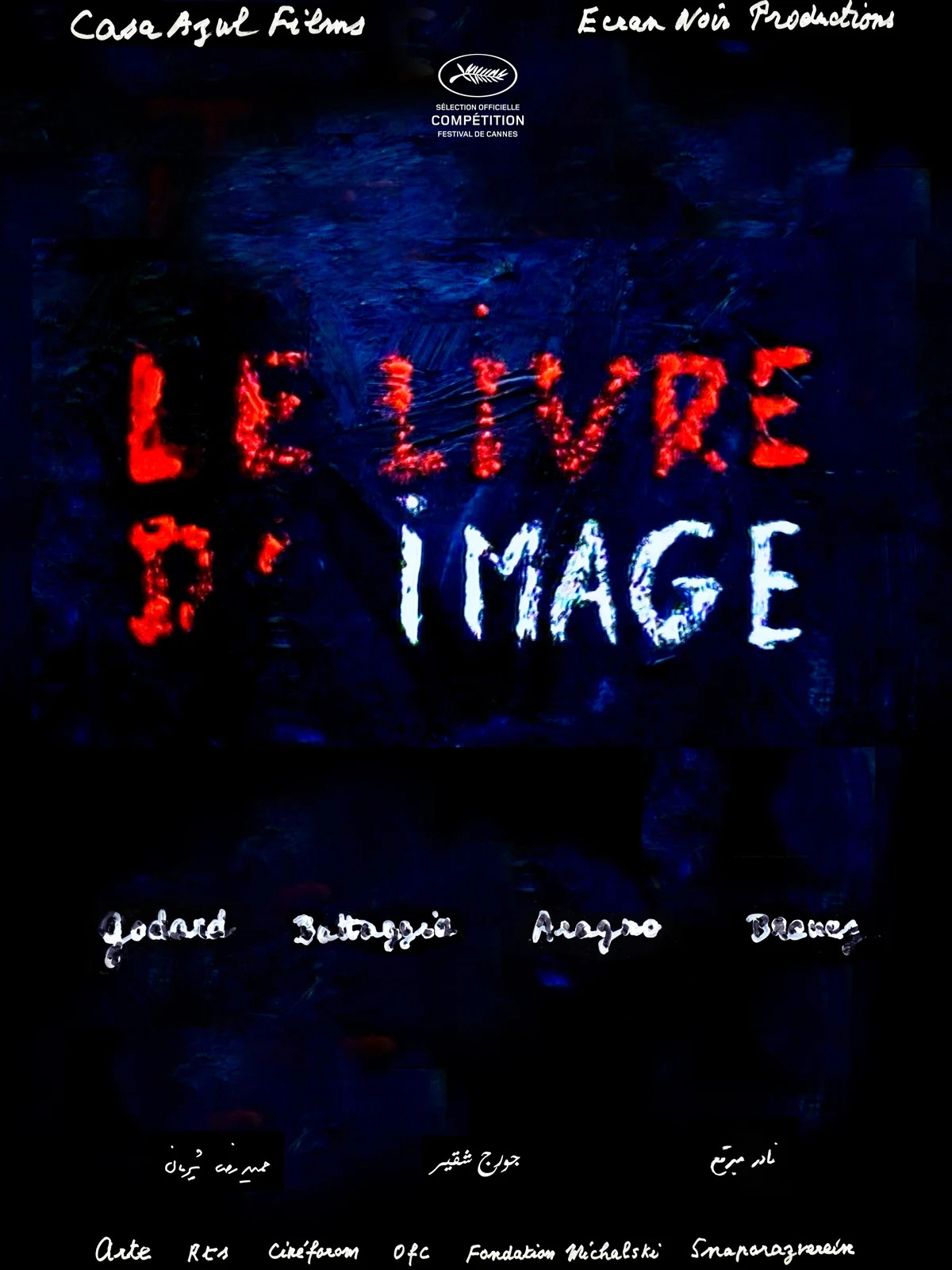

Directed by Jean-Luc Godard

Switzerland & France, 2018

It is not a just image, it is just an image - Jean-Luc Godard

And now for something completely different. This week’s film is a kind of video essay. Not, however, a 10 minute YouTube explainer that tells you why Deadpool & Wolverine is better than Citizen Kane. No, The Image Book is a dense and dizzying 86 minute work by Jean-Luc Godard, cinema’s great iconoclast.

Just five months ago ReidsonFilm reviewed Godard’s 1967 road movie, Weekend, and truth be told that film was not an enjoyable watch, but for Godard that is beside the point. Fifty years on, and in his late 80s, he was still going strong and surpassing the kids when it came to innovation. Because The Image Book is a collage, a visual cacophony of mixed media: paintings, photographs, mobile phone footage and most importantly perhaps, clips from classic films. All spliced together to illustrate Godard’s argument. And what is that argument? Well, just as with Weekend he remains as inscrutable as ever, but you can be sure that Godard will be saying something about the cinematic form and all its flaws, as well as predicting the apocalyptic collapse of society.

The first image we encounter is a fragment from Leonardo da Vinci’s painting of Saint John the Baptist – a solitary hand pointing up to heaven but suspended in darkness. It’s an image that recurs throughout the film, which itself is structured in five chapters. Five chapters for each of five fingers? It’s hard to say. Any attempts to interpret The Image Book are hampered by the sound, image, and even the subtitles intermittently dropping out – I wondered if the projector was breaking down. There is an element here of ‘guess what I’m thinking’; Godard is playing a game of auto-psychoanalysis.

The five chapter headings – ‘Remakes’, ‘Saint Petersburg’s Evenings’, ‘These Flowers Between the Rails, in the Confused Wind of Travel’, ‘Spirit of Law’, and ‘La Région centrale’ – are not especially illuminating. The cluster of images from the first four chapters seem to suggest a consistent theme: technology and its association with catastrophe. The clips, though, are distorted: pictures are smeared, colours hypersaturated or bleached away. If Godard is trying to send us a message here it’s cast adrift in his manipulation of the form. Instead, I found myself playing Spot-the-Movie: Johnny Guitar, Kiss Me Deadly, Henry Fonda as Young Mr Lincoln. And then in a shocking, or indeed crass, juxtaposition he cuts James Stewart’s Golden Gate Bridge scene from Vertigo with phone footage from ISIS, showing them tossing murdered prisoners into a river.

The cryptically titled third chapter is, ironically, the most comprehensible. A mashup of films depicting trains, starting with the Lumière brothers Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat from 1895, the film that famously caused panic among early viewers, convinced that a real locomotive was coming toward them. Buster Keaton’s The General makes an appearance and segues to trains arriving at Auschwitz. The message is clear: like cinema the railway has been central to both the rise of technology and the industrialisation of death. Society is founded on a shared murder, as the narrator, Godard himself, informs us.

The final chapter is the one however, that seems to be Godard’s principal focus – it lasts for over one third of the film’s running time. La Région centrale, the central region, is the Middle East. A catalogue of film, documentary, and extracts from novels and journalism illustrates how the West has exploited the Arab world through stealing not only its resources, but also by appropriating its self-image. Of course, only Godard can show us the Arab world as it really should be seen.

Amidst the allusions, the reframings, and the distortions there are some moments of arresting beauty. Yet the fundamental question remains… what is Godard’s purpose here? A didactically political film, meant to provoke thought and incite change? If so, a necessary starting point is for the audience to make sense of what it is seeing. As it stands, The Image Book is an abrasive watch, although in some ways it does fit with today’s Insta-TikTok-meme culture. After all, The Image Book could be ‘reframed’ as a 90-minute session of doomscrolling.

There is one more haunting image that comes after the closing credits. Godard's voiceover fractures, almost choked by a fit of coughing, while the screen shows a clip from Max Ophuls' Le Plaisir: an old man, dressed in evening wear and masked as a young dancer, twirling with can-can girls until he collapses – a dance to the edge of death.

Do think maybe bro should have just written an essay rather than subjecting me to such a discordant collection of random clips - felt like a crazy Foucault lecture while my professor was scrolling through his YouTube shorts algorithm - C

Reids’ Results (out of 100)

C - X1

T - 68

N - 70

S - 64

Thank you for reading Reids on Film. If you enjoyed our review please share with a friend and do leave a comment.

Coming next… North by Northwest(1959)

Being more of a film essay-cum-political meditation it seems redundant to try and place The Image Book on a scale with the films we have reviewed. It would be like scoring the viral Baby Monkey video with the same metric as Ingmar Bergman’s Persona.